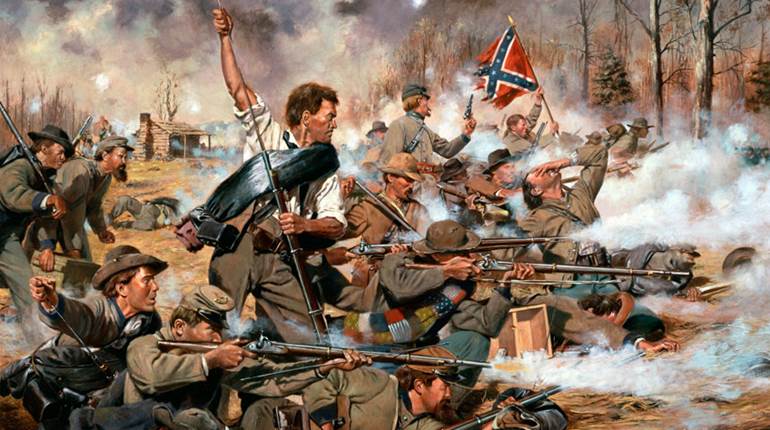

“The Gray Wall” by Don Troiani (1985) Private Collection/Bridgeman Images

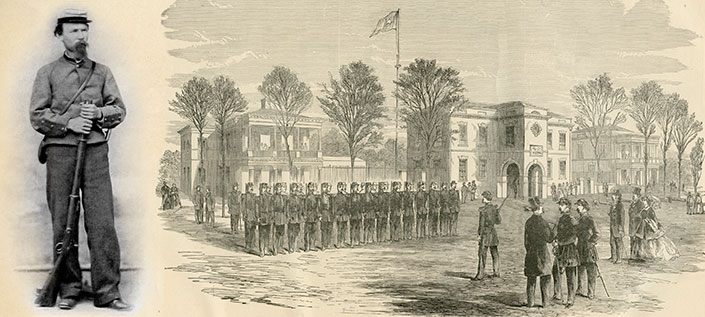

Civil War sharpshooter Berry Benson fought in several major battles with Gen. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Benson was captured and escaped from two notorious Union prisons before returning to his unit. At the war's end in 1865, he walked home with his two-band, London-made Enfield.

I first saw the monument in downtown Augusta, Ga., in 1966, as a young second lieutenant at nearby Fort Gordon. It was an impressive sight, and even though I was a Yankee from New Jersey, I was drawn to it. Statues of four Confederate generals, including the expected icons Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, along with lesser-known Georgians Thomas R. Cobb and William H.T. Walker, supported the base of a tall column topped by a figure of a lone infantryman at rest, a rifle in his hands. At the time I didn’t know that soldier was Berry Benson or, indeed, even who Berry Benson was. And then I left for Vietnam and my own war. Years later, while researching the Civil War and its small arms, I came across the story of Berry Benson and his Enfield rifle. And quite a story it was.

Born across the river from Augusta at Hamburg, S.C., in 1843, young Berry Benson proved exceptionally competent in spelling and mathematics at school and was an avid hunter and fisherman. At the age of 17, he was caught up in the political and emotional firestorm that led to the Civil War, and enlisted along with his younger brother, Blackwood, in a South Carolina militia unit besieging Fort Sumter. After witnessing the conflict’s first shots in April 1861, the Benson brothers marched off to Virginia with the 1st South Carolina Infantry. The 1st fought in the 1862 Virginia Peninsula Campaign and then marched north with Gen. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to Second Manassas, Antietam and Fredericksburg.

Through the winter of 1862-1863, Berry and Blackwood were selected for their brigade’s elite sharpshooter battalion. Sharpshooters were trained in marksmanship and skirmishing tactics and were issued imported .577-cal. British Enfield rifles, which were more accurate than the more commonly issued, longer-barreled rifle-muskets. Wounded at Chancellorsville, Benson missed the battle of Gettysburg but was back in the ranks by winter. In the early phases of the bloody Overland Campaign of 1864, his native intelligence and experience as an outdoorsman led to assignment as a scout, but on May 16 he was captured inside the Union lines at Spotsylvania, Va., and sent to the prisoner of war camp at Point Lookout, Md., located at the confluence of the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay.

Berry Benson, who had no intention of remaining a prisoner, evaded the camp guards and swam to freedom shortly after arriving at Point Lookout, but was recaptured and transferred to the prison camp at Elmira, N.Y. Then, after arriving at Elmira, Benson joined eight other prisoners in digging an escape tunnel, using his mathematical skills to guide the team’s work. The result, a Civil War version of the “Great Escape,” was the only successful breakout from Elmira. While his comrades headed for Canada and out of the war altogether, Benson walked south, determined to rejoin his unit. Incredibly, he reached Confederate lines in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia in late 1864, and after a period at home on leave, rejoined his sharpshooter unit in the defenses of Petersburg.

Upon his return, Benson was promoted to sergeant. His brother gave him a captured Spencer repeating rifle, which he used in the final fighting around Petersburg when the Union army broke through the Confederate defenses. Benson quickly used up his captured ammunition, discarded the Spencer and picked up an Enfield rifle. He carried that rifle as the Army of Northern Virginia retreated to Appomattox, where Lee surrendered to Gen. Ulysses Grant on April 9, 1865.

Although Berry and Blackwood Benson are listed on the roster of those who surrendered at Appomattox, Berry, reluctant to become a prisoner of war once more, slipped out of camp with his brother and headed south. When the Bensons discovered that the last significant Confederate force in the field had surrendered in North Carolina, they kept on walking, all the way home, where Berry stowed his Enfield and set about making a new life for himself in a new world.

Although it would seem unlikely, Berry Benson’s postwar career was, if anything, as compelling as his military experience. He married in 1868, had six children and, while working as an accountant, developed a complex book-keeping method he called the “Zero System” and sold it to companies all over the country. He also published well-received poetry; literature ran in the family—Blackwood wrote several popular novels, as well. Berry Benson became an advocate for striking mill workers and worked on developing high-protein food crops for poor African-American sharecroppers. Benson also became a nationally known puzzle solver, breaking a secret French code and offering his services to the United States during the Spanish-American War, which ended before he could be of use. He was perhaps best known, however, for his private investigation into the case of Leo Frank, an Atlanta factory manager accused of raping and murdering 13-year-old Mary Phagan in 1913. Perceiving discrepancies in prosecution testimony, Benson concluded Frank was innocent. His logical arguments persuaded the Georgia governor that there was enough uncertainty in the case to commute Frank’s sentence from death to life imprisonment, but that did not prevent the accused’s subsequent lynching.

Benson, who became a pacifist and vegetarian in his later years, remained active in numerous causes up to his death in 1923. He headed a campaign to support French war orphans in World War I, advised the U.S. attorney general of the possibility of fraud involving European and American fiscal exchange rates and, when he became aware of the activities of Carlo Ponzi, specifically warned the Massachusetts attorney general of the original “Ponzi Scheme.” In the midst of this productive life, Benson became an officer in the Confederate Survivors Ass’n and was chosen to model, holding his Enfield, for the statue of the infantryman atop the Augusta monument, which was dedicated in 1878.

There have been some questions raised over whether or not the Enfield rifle attributed to Benson and currently on display in the Augusta museum—donated by his daughter-in-law, who published Benson’s memoirs after his death—was actually the gun Berry Benson brought home from the war. Provenance of a wartime firearm used by an individual is often difficult with Civil War arms, even with Union soldiers recorded as buying a gun when mustered out of service in 1865. Claims that a particular firearm was brought home by a Union soldier prior to 1865 are possible, but unlikely, as permission to purchase was not given until 1865. Even with a record of purchase it is possible that a veteran may have bought a gun and then left it in the barn where it rusted away and, prompted by nostalgia, purchased a replacement from Bannerman’s surplus catalog in 1900. We will never know.

In Berry Benson’s, or any Confederate’s case, proof is even more difficult. What we can say is that Benson’s story holds up in all other matters, and there are images of him with an Enfield in the postwar era, including film of him marching with other Confederate veterans in a review before President Woodrow Wilson in 1917, and the rifle in question was donated by a member of his immediate family after his death. Considering all that, it is probable that this is indeed the gun he marched away with from Appomattox.

Some critics, who have never seen the Benson Enfield in person, bury themselves in minutiae and depend on the artist’s rendition of the gun in his hands on the monument. To settle the matter, I consulted with my Enfield expert, Bill Adams of the North-South Skirmish Ass’n, who is as knowledgeable in these matters as anyone I have ever known. Bill, a descendent of a Confederate veteran himself, verified that the Benson Enfield in Augusta was a London-made Pattern 1860. He went on to note that “My great-aunts were members of the Augusta Historical Society and also both knew Berry and Blackwood Benson. I got to see Benson’s rifle before it underwent one of those cleanings that were so popular with museum holdings in the 1960s and 1970s. The stock on Benson’s rifle was much darker when I first saw the rifle. The rifle has Confederate control numbers in the stock and a John Southgate ‘JS’ ‘Anchor’ inspection marking. Southgate was a British ‘viewer’ (we’d call him an inspector) who was retained by Caleb Huse as a viewer for the Confederates.” Adams’ analysis, coupled with the unique story of Berry Benson, convinces me that the rifle on display in Augusta is indeed the one he carried on that long march home in 1865.

And so, as I became familiar with the full story of Berry Benson and his life, I realized I was truly in the presence of greatness that summer day in Augusta—and it wasn’t that of the generals.