Radom pistols, or Vis wz. 35, as they are known in Poland, their country of origin, are currently enjoying a surge in popularity among collectors. While many praise their aesthetics, ergonomics and reliability, the dramatic role they played in World War II is also part of the appeal. The story of the pistol’s production under German occupation is rife with life-and-death situations experienced by the unwilling workers who made them, some of whom played a deadly game of cat and mouse with the Nazis, while others just tried to hold on to their lives.

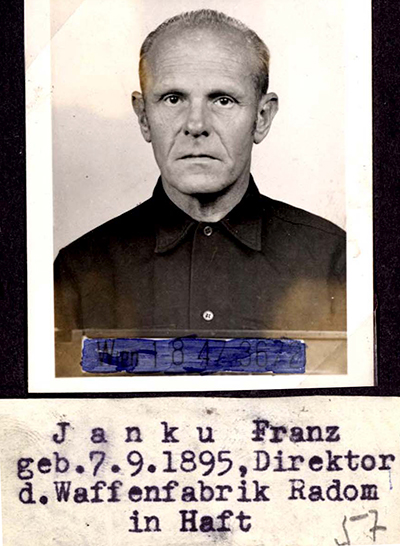

Originally designed as a Polish officer’s sidearm, the Vis pistol was manufactured from 1936 in Fabryka Broni (Weapons Factory), hence the initials “FB” on the left grip, located in the city of Radom. In addition to producing the pistols, the plant also specialized in making Polish variants of the Mauser Model 98 rifle and carbine. The Vis pistols were used by the Polish army fighting the German invasion in 1939. The Germans then took over the factory and put it under the auspices of the Austrian conglomerate Steyr-Daimler-Puch AG. The factory continued making rifles, but ceased pistol production until early 1941, when preparations were under way to invade Russia.

A series of about 3,000 pistols, all dated “1939” on the slide and stamped with the highest serial numbers recorded, holds one of the many mysteries in the history of the Vis 35. These pistols bear typical Polish markings, including a prominent Polish eagle on the slide, but the serial numbers on the slides and barrels generally do not match the frame. They are also missing the proper Polish acceptance stamp on the trigger guard and bear no German markings either. Previously, these were thought to have been produced in haste for the Polish military as the Germans were advancing. But, considering Radom was captured just eight days from the conflict’s start, such a large number could not have been produced in just one week.

According to Leszek Erenfeicht, editor of a Polish gun magazine and a Radom expert, these “mismatched ‘39 Eagles” were the first pistols made under the German occupation, likely with the primary purpose of retraining the pistol assembly crew. Before the official Heereswaffenamt acceptance unit (using the stamp “E/WaA77”) was established at Radom in 1941, these hodge-podge pistols were handed over to the German military without going through the standard acceptance procedure.

The work done at Radom was just one of the three stages in the pistol’s production. As before the war, some small parts, including the rear sight, extractor, grip safety, decocking lever and magazine, were made at Fabryka Karabinów (Rifle Factory) in Warsaw and then shipped to Radom. At the Radom factory, slides and frames were made, and the pistols were fitted together. Knowing that the bulk of the work would have to be performed by local Polish workers, whom they did not trust, the Germans moved the barrel production and final acceptance to the parent Steyr factory in Austria.

If this move was to prevent the pistols from getting into the hands of the Polish resistance, it failed. The resistance quickly established a network among the employees that began smuggling pistols out of the factory. The initial supply of barrels for the underground came from parts pilfered by patriotic workers before the Germans established security in the conquered plant in 1939. When these ran out, an underground shop was established in Warsaw for the purpose of making the barrels. As one resistance report states, there were 200 barrels produced in a six-month period between 1943 and 1944, which gives an idea about the rate at which the pistols were smuggled. One participant describes in detail how the smuggling operation worked: “When we were directed [by factory management] to go on a supply run ... to fetch steel, oxygen, or other materials, [my partner] would meander around the truck, getting it ready for the road, and I would go to the steel warehouse to see my friend ... . The friend had a job at the warehouse, while other resistance members who worked at the weapon assembly division would bring the Vis pistols to the warehouse and conceal them on the shelves where the steel was. I would go up to the shelves and stuff two, three, and sometimes even four pistols under my waist, then head for the car garage and conceal them in the truck cab. I would put them under the seat, under the gas tank, or inside the spare wheel [compartment] by attaching them to the tire with chicken wire. Then we’d get on the road. At the gate, the security guard would check the truck bed and look around, but the pistols were always well concealed.”

This was just one of the ways in which pistols were smuggled. More typically, they left the factory in official capacity, but the documents were falsified to give a higher number to the security checkpoint when leaving the factory than what arrived at the destination. On the way out of town, the truck would stop by a storefront run by one of the resistance members and drop off the extra pistols.

One technique that facilitated pistol smuggling was the cloning of serial numbers. Unlike a pistol without any serial number, a cloned pistol would arouse no suspicion at the factory, so long as it was kept away from the original. The serial numbers were stamped early in the production process on the frame and slide—and the person assigning the numbers was a member of the resistance. At the end of the production line, the foreman in charge, also a resistance member, would set aside the parts with cloned numbers and carry them to the steel warehouse. Once the cloned pistol left the factory grounds, the serial number would be removed to make it harder to trace, should the pistol fall into German hands.

For a time, the Germans were completely unaware of the smuggling operation, until one day in September 1942, when a six-person commando of resistance fighters was traveling by rail to execute a Nazi collaborator. The commando was armed with the smuggled Vis pistols. Once on the train, they were surrounded by the Gestapo, and a shootout followed. Four of the fighters escaped, killing one of the Gestapo guards and wounding two more, but one fighter was killed, and worse, another captured.

During the shootout, two cloned Radom pistols fell into German hands, one with its serial number removed and one with the number still intact. The removal procedure was not performed adequately either, and the forensic experts in Berlin were able to reveal the number on the first pistol anyway. Both were traced to police units in occupied Poland, which still had them. The Vis production line was closed at the Radom factory, and additional parts with duplicate serial numbers were revealed. As a result of the usually brutal investigation that followed, in October 1942, 50 people were hanged in a series of public executions—some at the train station where the shootout happened, and some at the factory grounds where the pistols were made. The discovered breach also had an immediate effect on production procedures. Beginning with the “J” alphabet prefix series, the frame and slide received two additional control stamps, which presumably made it more difficult to counterfeit.

While the smuggling operation was going on, another group of workers had a whole different set of concerns. Beginning in June 1942, the Germans started employing Jewish slave labor at the factory. Holocaust in Radom was taking place in a similar manner to other places under Nazi rule. In a constantly tightening spiral of regulations, people of Jewish ancestry were first stripped of their dignity, public rights and possessions, then relocated into fenced ghettos and, finally, sent off to death camps. Radom was different in that its industry was largely geared for war production. The strong industrial lobby, which was eager to take advantage of free slave labor, was able to temporarily ward off the head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, who wanted to exterminate the Jews as quickly as possible. And thus, through cynical power play among the Nazis, a small number of Jews had a chance to avoid the death camps by proving useful to the German war machine.

As the ghetto was being liquidated in Radom, a concentration camp was set up near the factory in the fall of 1942. According to Polish resistance intelligence reports, the number of Jewish prisoners employed at the factory stabilized in August of 1943 at 1,200, out of the total of about 4,500 workers.

While not being a target of mass extermination, the prisoners were nevertheless being constantly abused and terrorized. In November 1943, 26 Jewish workers at the Radom factory were shot for unsatisfactory work, and seven Jewish workers were hanged for “sabotage” the next year. Robert Muller, head of the metalworks department, shot a worker on the spot who fell asleep at a machine. Muller, additionally, singled out women and subjected them to physical and sexual abuse. Johann Reich and Joseph Martyn would severely beat workers who could not keep up with the daily quota. This is in addition to the fact that being considered unfit for work meant selection for shipment to a death camp.

Remarkably, I was fortunate enough to interview Dora Zaidenweber, a Holocaust survivor and the last living person to have worked on the Radom production line. For the first time in more than 70 years, she recalled the circumstances of that experience, and her story is absolutely riveting. (See sidebar story below)

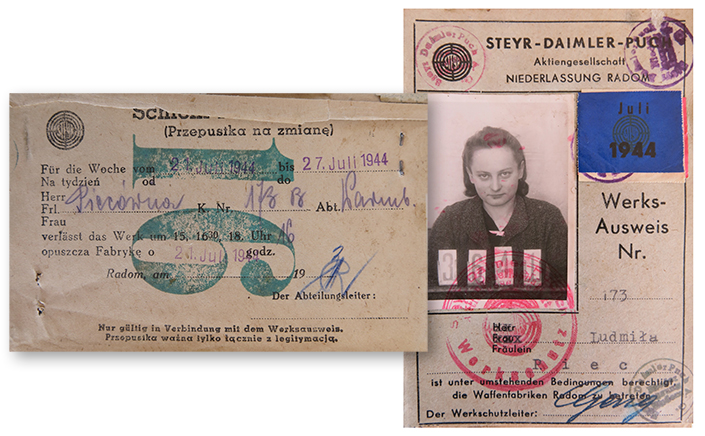

As the Russians advanced to the Vistula River, 15 miles from Radom, the Germans decided to abandon the factory. On July 25, 1944, the civilian crew was let go, and the prisoners were marched on foot toward the Auschwitz death camp. Upon seeing that the Russian offensive stalled, the Germans returned to the factory and evacuated the production line to Znaim a couple of months later where they continued making the Vis pistols in small numbers until the factory was finally bombed out of business on March 8, 1945.

An Interview With Dora Zaidenweber

An Interview With Dora Zaidenweber

Dora Zaidenweber is a public speaker and a survivor of the Holocaust. Her father was deported to Auschwitz in 1942 and survived the war in the infamous death camp. She is the translator and editor of his memoirs from the camp, titled Sky Tinged Red. At the time of the interview, she was the last living person to have worked in the Radom pistol factory under Nazi occupation.

When did you start working at Radom factory?

“It was about September of 1943 when I was put in the concentration camp on Szkolna Street, which was a subdivision of the Majdanek camp. Prior to that, I was at a forced labor camp on Szwarlikowska Street. As that camp was being closed down, my husband approached a high school friend of his, Jerzy, about working at the factory. Jerzy was a Pole who was studying in Warsaw to be a doctor. But war interrupted his medical school and, at the time, he had been working as a medic at the factory in Radom. He came through for us: We got moved to the Szkolna Street camp and started working at the weapons factory.”

Did any Jewish prisoners work in the weapons factory before that time?

“I know that at first men marched to the factory from the camp on Szwarlikowska Street, before Szkolna Street camp was established closer to the factory.”

How did your day begin?

“In the morning, around 6 a.m., we always had formation. We were lined up next to our barracks. The administrative person at that barrack took the head count, gave it to the SS man, the SS man checked the count and then we were marched out. Out of about 3,000 people in the camp there were about 1,500 who went to the factory, and the rest stayed behind and worked on upkeeping the camp. We worked 12-hour shifts, six days a week, with Sundays off.”

How did your day end?

“The same procedure as in the morning was observed at the factory when we left our stations. At the end of the day, at 6 p.m., we were lined up, counted again and we marched back to the camp.

“There was one incident of escape that was found out at the end of the day. We stood in formation at the factory grounds for hours until the entire factory was searched. They did not find the person. Nobody knew who it was, because the counting was done by numbers, not by names. Only later, through the camp records, it was found out it was a young woman. The gossip was that she was helped by somebody on a motorcycle. A Polish man took her out and left the factory with her.”

What did you do at the factory?

“At first, I was working in the woodshops, where the carpenters were making boxes for the pistols. They were small boxes, consisting of top and bottom parts, just big enough for one, maybe two pistols. They were lined inside with material and beautifully finished. I was curious about why so much work went into making these boxes, and was told that those guns were for export outside of Germany. My job was to finish the wood to a shine by rubbing a polish into it. The work required hard motion with your hand, and I remember my arm was very sore from it.”

Who were the people you worked with at Radom?

“They were also Jewish prisoners, all male. As highly trained carpenters, they were making cabinets for the German hierarchy in the shops at the factory. I originally got the job because I knew how to apply varnish, but it wasn’t varnish they were having me apply. They had to train me at how to apply the polish. At 19 years old, I was the only girl there, and they were all very nice to me.”

Being the only woman there, were they flirting with you?

“No, they were much older. They just felt sorry for the young girl. It was very nice to work there. I don’t remember how I lost that job, but the next job wasn’t so nice anymore. It was at the factory building, and I was in constant fear there. There was no visiting with other workers in that place. I was stood in front of a machine and told to punch holes in the pistol frames.”

This was when you first saw the Radom Vis 35 pistol?

“Yes, I held these frames in my hand. I’m looking at my hand—the pistol wasn’t much bigger. And I have pretty small hands. By the time the frames made it to my station, a lot of operations were done on them, and mine was one of the last ones. The job was to punch a square hole, about the size of a child’s nail, in the top part of the frame. For each frame, I had to manually lower the machine to check that it did not come out of alignment and that the punch was going to make a hole in the right place. After checking the alignment, I would turn on the machine, and it went on its own. You could hear a series of punches as it made the hole.”

What were your working conditions like at the factory?

“I don’t remember much of the working conditions from this station. I don’t remember any people or how the production line was set up. You were supposed to stand by your station and keep to yourself, so there was no interaction with other workers. I only had to punch holes in 75 frames during my shift, so the job was very boring. You had nothing else to occupy your mind with, except that little hole. At the same time, the responsibility was enormous. The frames were almost finished, and a single mistake at my station would spoil the whole work. That would be considered sabotage, and I was in no position to do that. Furthermore, we worked alternate shifts: day and night. During the day it was tolerable, but at night it was a disaster. I struggled to stay awake at the factory, and then I could not get any rest back in the camp, because there were other people there and it was noisy.”

What happened if there were defects on a pistol?

“I don’t know first-hand, because I never had any defects. I did not see anyone abused at the factory, although I’m sure it happened. I think I had it easier, because I was a woman, but if I were to spoil a pistol frame, I would probably be severely beaten. It was very traumatic, I was afraid all the time.”

How did you manage to get a different assignment?

“I was so famished from just standing there for hours that I asked to be reassigned. I don’t remember whom I asked, but it was some Jewish elder. I was extremely relieved that they found another place for me.

“My new assignment didn’t carry as much responsibility. Another woman and I were making these tiny metal cubes. The cubes were made of gold-colored metal and were less than half inch in size. We were making about 300 of these each, and only had to work during the day. The work happened in a large hall. It was open on one side, which led to another part. There was an aisle in the middle, and on each side there were machines where Jewish men were working. At the end of that aisle, off to the side, was the station where the other woman and I were working.”

How did you get along at that new job at the factory?

“My co-worker was a Polish woman who was not in the concentration camp. At the end of the day she went home. She was extremely mean to me, because I was Jewish. I did not talk to her and kept to myself. Our foreman was Ukrainian, and he hated us both: me, because I was Jewish, and her, because she was Polish. He didn’t talk to us except for telling us what we had to do. The head of this small department was an ethnic German by the name Adler. He was a civilian who could understand Polish. Him, we were most afraid of. Nobody spoke a word when Adler was walking by. Fortunately, he wasn’t around much.”

As the front line was creeping closer to Radom, do you remember any air raids, electricity outages or any other interruptions?

“No, I don’t recall any disruption of production. We were hearing rumors about the Russians getting closer, and one day we heard they crossed the Vistula River and were in the village of Kozienice, about 20 miles east of Radom. The following day, some time in July of 1944, we were told to get our things, and were marched, on foot, towards Auschwitz. It appeared that the factory was functioning normally the day before, and no preparations were made for evacuation.”