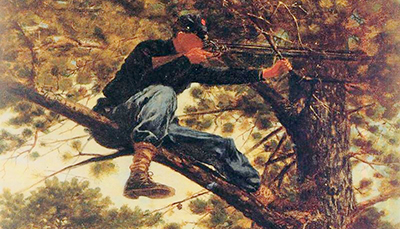

“Breechloaders and Greencoats” by Dale Gallon depicts men of the 2nd Regiment of U.S. Sharpshooters at Gettysburg. This is the third article in a series by former curator of the Royal Armouries Martin Pegler. The previous installment can be read at americanrifleman.org/genesis2.

When the war between the Union and Confederacy began in 1861, men flocked to the ranks from every walk of life. Invariably, there were a large number of very competent shots, but initially no attempt was made to harness their skills. From the outset, it was obvious that equipping the ordinary soldier of either side with an accurate rifle was not going to radically change the methods of fighting. As witnessed in the Crimea (August 2016, p. 56), having a rifle capable of accurate shooting in excess of 500 yds. was of little use if the men using them had not been properly trained, and the tactics on the Civil War battlefields remained unchanged from those of Napoleon.

In the bloody clashes between North and South the battlefield was, as ever, quickly blanketed by thick smoke generated by blackpowder, obscuring any potential targets. Frightened, inexperienced soldiers in serried ranks loaded and fired their muskets as fast as possible without resorting to aiming or adjusting their sights. In fact, many longarms examined after combat were found to contain multiple loads, the men not even realizing they had failed to discharge their arms.

The Northern Army was mostly (but not exclusively) armed with Model 1855 rifle-muskets, primarily manufactured by the Springfield and Harper’s Ferry arsenals—although these were gradually supplanted by the improved Model 1861. Confederate forces had a more disparate selection, including Model 1855 copies made by Fayetteville and Richmond arsenals as well as other state-made longarms by smaller companies, such as Cook and Tyler. There were also large numbers of obsolete smoothbore muskets held in store, including many flintlocks, and large numbers were converted to percussion ignition.

Union Sharpshooters

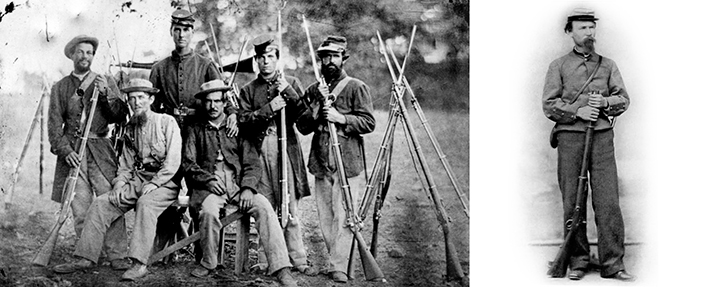

The one exception to this organized chaos was the equipping of sharpshooters, scouts and pickets whose positions on the flanks or in advance of the main forces permitted them to see and engage the enemy before any other soldier. Of course, to enable them to do this they needed accurate rifles. One of the first senior officers to appreciate their value was Gen. Hiram Berdan, a very skilled shot in his own right. He organized the recruitment of 10 companies of sharpshooters, organized as the First (and later, 2nd) Regiment of United States Sharpshooters (U.S.S.S.). Those who applied had to pass a tough shooting test to be considered. From the shoulder, they had to place 10 consecutive shots in a target at 200 yds., the group not exceeding 5"—and many men could better that. Once enlisted in the ranks, men were taught range estimation, observation and camouflage in a series of classes that would not be unfamiliar to today’s snipers. Although Berdan was disliked by the military establishment (he was arrogant and opinionated), no one could argue that he did not know exactly what he wanted when it came to equipping his sharpshooters.

Like the British rifle regiments of the Napoleonic war, Berdan’s men were clothed in practical green frock coats and trousers with black buttons, which blended with both summer and winter foliage. But most importantly from the perspective of both the general and his men was the requirement for them to be armed with the best possible rifles then available. This brought Berdan into direct conflict with the conservative Brig. Gen. J.W. Ripley, chief of ordnance. Berdan wanted nothing but the breechloading New Model 1859 Sharps rifle; Ripley did not, although in his defense it must be said that the Sharps was three times the cost of a Springfield and required a non-standard caliber of cartridge. After a disastrous period in which the Sharpshooters were issued the much-detested Colt Model 1855 Revolving rifle, Berdan went over Ripley’s head, obtaining the incontestable backing of both President Lincoln and the venerated Gen. Winfield Scott.

The Sharps was a breechloading caplock that chambered a combustible .52-cal. cartridge, and it was renowned for its long-range accuracy. The special-order rifles purchased for the 1st and 2nd U.S.S.S. had 30" barrels, and most sported double-set triggers with sights marked for 700 or 800 yds. Around 2,000 were supplied, and in the hands of the Sharpshooters they proved devastatingly effective. Berdan’s men routinely shot at ranges of 500 yds. and beyond, and, given good conditions, 1,000-yd. shooting was not uncommon. One Sharpshooter, having watched with frustration as a group of Confederate artillery observers stood on a raised observation platform at an estimated 1,200 yds. distance, added extra graduations made from card to his rear sight. He settled himself into a comfortable position and began firing. Whilst it is not recorded that he actually hit anyone, observers commented that the Confederates quickly abandoned their lofty perch. In an equally remarkable feat of marksmanship, two Berdan men, Corporal Abner Johnson and George Fisher demonstrated what a Sharps was capable of at Kelly’s Ford on Nov. 7, 1863. As rebel troops retired, Johnson was urged to try and hit a distant straggler. He raised his rifle and said “I’ll try him,” and, allowing two feet for windage, set his rear sight at 700 yds. and fired. Meanwhile, George Fisher also responded to pleas to “down that fellow.” He, too, loaded his Sharps and simultaneously fired at the same unfortunate Confederate soldier. The man threw up his hands and fell. Upon advancing, the Union soldiers were amazed to find him still living, albeit with one bullet through the right thigh and another through the left hip.

Of course, issue rifles were not the only arms used for sharpshooting, and many hundreds of men joined the army carrying their own favored rifles. As a type, these most often comprised bull-barreled target guns, with Malcolm or Morgan James pattern telescopic sights fitted. They were certainly accurate, but were invariably of non-standard calibers, typically between .36 and .45, which meant the riflemen had to make their own ammunition. They could also be monstrously heavy, 25 lbs. not being uncommon, but were generally too fragile to stand up to the rigors of the battlefield. Berdan commented dryly that he had a wagon full of these rifles, which were of little practical use in combat. That was not always the case, however, for sharpshooter Truman Head—universally known as “California Joe”—frequently used his own massive bull-barreled rifle for dealing with enemy marksmen. The make of the gun is unknown, but was described as being six feet in length, weighing 32 lbs., with an octagonal barrel, silver mounts and a full-length scope that “… will make a man who is a mile away look as though he was only 200 or 300 yards off.” During the Siege of Yorktown (April 5–May 4, 1862), Joe singled out a troublesome Confederate field gun and Chaplain W.H. Cudworth of the First Massachusetts Regiment later wrote, “He obtained such perfect control by picking off the men as fast as they endeavoured to load and fire it, that he called it ‘his gun’ and as long as he remained in front, it truly seemed to be; for it was very seldom discharged, except at night.”

Confederate Sharpshooters

The belief that the Southern states were unable to field sharpshooters of the same standard as the Federal army is an erroneous one, although shortages of rifles and training initially hindered their development. The Southern troops wore a practical butternut or gray uniform, which blended well with the foliage, and a range of shapeless slouch hats did a fine job of obscuring distinctive facial features. Their sharpshooter units differed from the North in being raised from local units. So, rather than a specific regiment of sharpshooters such as Berdan’s 1st U.S.S.S., there existed 16 sharpshooter battalions, which comprised units made up from regiments raised across the Confederacy. Initially they did not perform well but, as the war progressed under the guidance of good commanders, they began to excel in their work. Their training was every bit as intensive as the Northern sharpshooters with great emphasis placed on range estimation, as Maj. William Dunlop wrote “… until every man could tell, to a mathematical certainty, the distance to any given point on the compass.” Shortages often meant that the Confederate sharpshooters wore an eclectic mix of issue, civilian and captured clothes often resulting in soldiers who were, as one Union soldier put it, “Scare recognisable [sic] … in a variety of common clothing fit only for scarecrows.” Frankly, for the job they undertook, such a mix of clothing proved to be of more help than hindrance.

The problems that the Confederacy faced in obtaining good rifles were manifold. Not only did the ships delivering guns have to run the Union naval blockade, the risks of which were reflected in astronomical delivery costs, there was also the fact that many of the rifles purchased by the South were obsolete models that their former European owners were only too delighted to sell at inflated prices. The Southern armies were equipped with a broad range of Confederate-made rifles, but foreign imports were a vital part of their arsenal. Of these the most widely available and highly-regarded were the .577", Pattern 1853 Enfield rifles. Contrary to some current beliefs, these were not British government manufactured guns but were all purchased from contractors in London, Birmingham and Liege in Belgium. More than 1 million were supplied to the Confederacy during the war, and all were made to a very high standard. Major Dunlop, responsible for much of the intensive training that was given to the Confederate sharpshooters, wrote of a comparative test undertaken between a number of issue rifles including Springfield and Richmond rifle-muskets and the Pattern 1853.

“The superiority of the Enfield at long ranges, from 600 to 900 yards, was clearly demonstrated both as to force and accuracy of fire. The Enfield proved reliable and effective to a distance of 900 yards, while the other rifles could only be relied on at a distance of 500 yards.”

Although the P’53 was greatly prized, the shorter, 30"-barreled two-band Enfield Musketoon, the Model 1861, was also highly popular. Although not having the extreme range of the longer rifle, it was lighter, easier to carry and, in experienced hands, accurate up to about 600 yds.

Far rarer were the expensive Whitworth rifles, which gained almost mythical status among Confederate sharpshooters. Sir Joseph Whitworth, a brilliant British engineer, had been requested to design a replacement rifle for the Pattern 1853. The result was, even by the inventive standards of the time, a truly exotic firearm. It employed a unique .451 bullet that was hexagonal, requiring naturally enough, a hexagonal bore from which to shoot it, barrel lengths being normally 36" or 39". It was extraordinarily accurate, in part because every cartridge manufactured was made by hand to the most exacting standards. In British army tests during 1856, at extreme ranges, the Enfield proved capable of hitting a 12-ft. square target at just more than 1,400 yds. A Whitworth was able, repeatedly, to strike the target at a phenomenal 2,000 yds. If there were problems with the Whitworth it was that it suffered from a very high level of fouling and required meticulous cleaning—and it was four times as expensive as an Enfield rifle to manufacture. Unsurprisingly, the British government rejected it, but Whitworth found an unexpected market with the Confederacy, who bought as many of his rifles as they could afford. Whilst a locally made Confederate rifle such as a Fayetteville cost perhaps $25, an imported Enfield, whose normal commercial retail price would be $125, could cost the South $600. A cased Whitworth with 1,000 rounds of ammunition was a staggering $1,000 (or around $15,000 at today’s value). If the Whitworth had a telescopic sight, then that price rose by another $200, or the equivalent cost of eight issue rifle-muskets. Out of the production run of approximately 1,500 rifles, exactly how many were supplied to the South is unknown, but one Confederate division alone was recorded as having received 30 Whitworth rifles and “16 Kerr’s.” (The .442 Kerr was also a highly accurate rifle, albeit firing a more traditional cylindrical bullet). Overall, the Confederacy purchased anywhere between 100 and 500 Whitworths.

The Value Of Sharpshooting

Exactly how one can quantify the value of sharpshooters during this, or any war, is nearly impossible. Union marksman killed no fewer than six Confederate generals, whilst some 60 officers over the rank of major were killed on both sides by sharpshooters. Probably the most celebrated victim of a sharpshooter’s prowess had to be Gen. John Sedgwick, whose dismissive attitude toward men who were dodging the distinctive hissing noise of the Whitworth bullets was to cost him dearly. As one man took cover, Sedgwick asked: “Why are you dodging like this? They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.” At which point a bullet, most likely fired by a Whitworth-armed sharpshooter named Sgt. Ben Powell, struck him below the left eye, killing him instantly. The distance of the shot, though still disputed, is believed to have been around 800 yds. As a broader example of the effective use of sharpshooters, during the First Battle of Dalton, (Feb. 22-27, 1864) 46 rebel sharpshooters, mainly Whitworth-armed, defeated a determined attack by Federal troops. It was later remarked that “So galling was the fire, that any man who attempted to rise, was shot dead.”

If the loss of senior commanders was incalculable, so too was the psychological impact on the ordinary soldier, knowing that at any given moment a hidden marksman could end his life. The tactics learned by sharpshooters proved to be of inestimable value in the conduct of the war. Of course, neither should it be forgotten that as a result of the conflict and the recognition of the value of accurate shooting, a scant six years after the conflict ended in November 1871 the National Rifle Association of America was founded.

The question as to whether the experience gained in sharpshooting during those terrible years was to prove of future military value will be the subject of a future article.