Although a bit too large for Col. Cooper’s “ideal” scout rifle criteria, Savage’s Model 11 Scout does provide shooters with a firearm that is handy, adequately powerful and affordable.

It’s pretty much impossible to mention a scout-style rifle without a reference to Col. Jeff Cooper, who popularized the concept. Cooper’s Scout was designed as a “one rifle to do it all” tool for the highly mobile warrior/hunter from which the “Scout” name was derived. A scout rifle would be compact, lightweight, accurate, capable of a reasonable rate of fire and chambered in a cartridge sufficiently powerful to defeat a variety of targets. Savage Arms’ Scout aims to meet Cooper’s definition in a modern, affordable, production-ready package.

Savage’s Scout is built around the company’s Model 11 short action. This turn-bolt, push-feed design uses a floating bolt head to align the cartridge with the chamber, an element that helps contribute to Savage’s reputation for accurate rifles. The Scout feeds from a 10-round detachable box magazine that is built from a combination of stamped steel and polymer. Care must be taken to fully seat the magazine or the rifle will not feed; at numerous times during our evaluation, we thought that the magazine was seated correctly when it was not. A small sliding-plate extractor grips the cartridge rim once the round is chambered and a plunger-type ejector extends past the bolt face under spring tension. The striker protrudes slightly from the rear end of the bolt assembly when the gun is cocked.

The Scout comes with Savage’s well-regarded AccuTrigger, which has a secondary blade that must be depressed before the main lever can release the striker. The design balances safety concerns with a reasonable trigger pull weight and is user-adjustable. Our example broke at slightly more than 3 lbs. as it came from the factory and was certainly an aid in maximizing the accuracy potential of this rifle. The manual safety is on the tang, directly behind the bolt’s cocking piece, and has three positions: At its rearmost, the safety locks the bolt and the trigger; one step forward allows the user to operate the bolt with the trigger locked; and the forwardmost position allows the rifle to fire.

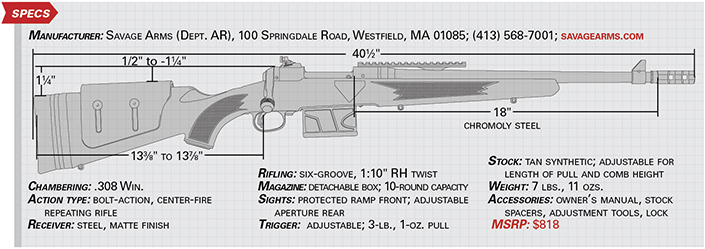

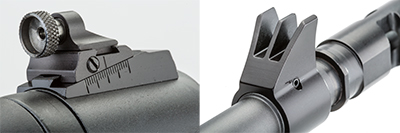

In order to maintain the scout concept’s compact overall length dimensions and light weight, the Savage Scout wears an 18" button-rifled barrel that is of a light contour. A four-port muzzle brake adds some length to the rifle but reduces recoil significantly. That reduction in recoil comes at the cost of increased muzzle blast, and double ear protection is a good idea. A key part of the scout concept is an optic mounted forward of the receiver, both to allow the shooter access to the action and to facilitate faster target acquisition. The Savage Scout uses a Picatinny rail that extends from the receiver ring onto the barrel to locate either an extended-eye-relief scope or a red-dot optic in such a position. An inexpensive 2-7X 32 mm Hi-Lux scope was used for our testing and, but for its unreliable adjustments, proved generally serviceable. Colonel Cooper’s experience taught him that complex optics were prone to failure in hard use, therefore iron sights are a requisite on any true scout rifle. The Savage uses a sturdy, serrated-ramp front sight mounted to a barrel band just behind the muzzle brake—reminiscent of the M1 carbine. Like the M1, the Scout’s front sight is protected from damage by an ear on each side of the central ramp. The rear aperture sight is an adjustable model from Williams that is mounted to the rear of the rifle’s action. These sights are far more durable and functional than the vast majority of sights found on today’s production sporting rifles. Many shooters accustomed to using a scope would be surprised at how effective a good set of iron sights can be at moderate distances.

The Scout is stocked in tan polymer with a soft recoil pad and an adjustable length of pull. A stock that has the correct amount of drop for use with iron sights is often unsuited for scope use, and vice versa. Savage corrects this conundrum on the Scout with an adjustable cheekpiece that allows the shooter to set the correct stock height for whichever sighting system is used. The cheekpiece is adjusted by loosening two hex screws, sliding the cheekpiece to the preferred setting and re-tightening the screws. Likewise, the length of pull is adjusted by adding or removing spacers that are sandwiched between the recoil pad and the body of the buttstock. The stock comes equipped with three sling swivel studs—two forward so that a bipod or three-point “Ching sling” can be used without modification—and one aft. Despite the internal AccuStock aluminum bedding block, the stock on the Scout lacked rigidity, particularly at the fore-end, which became a factor on the range. Glass bedding would vastly improve the situation.

Accuracy with two of the three loads tested was fair, though one load shot very well. Until we shot groups with the Prime ammunition, we began to suspect that the scope had failed internally. Group sizes and points of impact shifted noticeably depending on the rifle’s position on the front sandbag rest, likely due to flexibility in the fore-end. Reliability was good unless the magazine was loaded with a full 10 rounds, in which case, the top round would sometimes spring upward when engaged by the bolt, causing a stoppage.

To meet Cooper’s definition of a scout, a rifle must adhere to a rigid set of criteria which includes a maximum unloaded weight of 7.7 lbs. including a scope and sling, an overall length of less than 39", and accuracy potential of 2 m.o.a. or better. The Savage Scout is too heavy and a hair too long to completely fulfill Cooper’s standards, but otherwise meets the criteria. This modern take on Cooper’s design incorporates the core elements of the scout concept while maintaining the cost-effectiveness for which Savage is known.