The last decade of the 19th century must have been a fascinating time to be alive. New inventions and improvements on current ones arrived on scene in a staccato rivaling the firing rate of a machine gun. Two of the giants in the handgun industry—Colt and Smith & Wesson—were locked in a dogfight as to which company would garner the lion’s share of that market. Colt had the lead with its Single Action Army revolver. The company has historically relied on relatively simple, rugged designs, superbly executed to establish and maintain market superiority. Its Massachusetts-based counterpart, on the other hand, hangs its hat on intricate designs with precise execution, that is aesthetically pleasing and with an impeccable finish to set it apart.

Then, as today, customers—both civilian and military—pine for a firearm that is light in weight to lessen the burden of carrying it constantly. They also want it to be powerful enough to be effective, and they want it to be easy to shoot and hit the mark. Those of us who have been around guns for some time know the contradictions, but people still want a 4 oz. gun that hits like a .44 Mag. and is as easy to shoot accurately as a .22 LR target pistol. The companies, alas, continue to try to accommodate this dream.

Colt had already developed the concept of a double-action or trigger-cocking revolver back in 1857. Its first successful double-action revolver was the Model 1887 Lightning. These first revolvers countered Colt’s reputation for ruggedness and were rather fragile. The Model 1887 Thunderer was a similar piece in a heavier caliber, .41 Colt. Then, utilizing William Mason’s 1865 patent for a swing-out cylinder with simultaneous ejection, Colt brought out the Model 1889 Navy, a.k.a. New Navy DA Model of 1889. Three years later the less-than-stellar Model 1892 Army debuted, followed by the beefy and robust New Service in 1898. Customers liked the New Service for its performance, but, again, pined for something easier to carry all day long every day.

Smith & Wesson continued to nip at Colt’s heels, spurring the Connecticut gun maker to relentlessly pursue improving its design. Colt responded in 1896 with its New Police Revolver, a relatively small frame double-action revolver with a swing-out cylinder holding six rounds of .32 Colt cartridges. The frame was derived from Colt’s New Pocket Revolver that was introduced the year before. New York Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt chose the New Police Revolver to be the first standard issue revolver to the NYPD in 1896.

After getting its nose bloodied by Smith & Wesson in 1898 with its Hand Ejector Model, Colt hurried to add a device to allow its revolver to be safely carried with all six chambers loaded. The Police Positive debuted in 1907. “Positive” was derived from Colt’s nomenclature for the internal hammer block safety device. The marketing guys at Colt had to do something to gin up the enthusiasm beyond a safety device so they latched onto the notion of a clockwise-rotating cylinder, claiming that it was stronger and less wearing on the crane than Smith & Wesson’s counter-clockwise-rotating cylinder. Never letting a good marketing notion go to waste, they further made the unsubstantiated claim that the clockwise-rotating cylinder was more accurate.

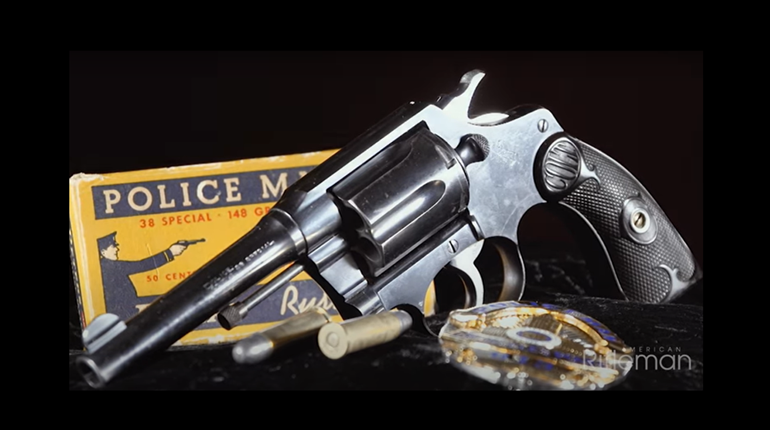

The Police Positive did find a lot of favor, especially with door-rattler cops who shot relatively little but carried daily. It carried on the .32 Colt chambering but added the .38 Colt New Police (a.k.a. .38 S&W) chambering for added punch. Sights were a fixed groove in the topstrap and a half-moon blade up front. Barrel lengths were 2 1/2", 4", 5" and 6". Grips were checkered hard rubber until 1924 when checkered walnut became standard. Finish could be blue or nickel. In 1908 the frame was lengthened a bit to accommodate longer cartridges. Chamberings included .32-20 WCF and .38 Spl. These were named the Police Positive Special. Colt’s D-frame was further beefed up in 1928, and they began serrating the topstrap to reduce glare. These revolvers are known as Police Positive Second Issue.

A target version chambered in .22 LR with adjustable sights became available in 1910. Later iterations of the target model were chambered in .22 WMR, .32 Long (and Short) Colt, and .32 Colt New Police (.32 S&W Long). Today the target variation carries an 80 percent to 90 percent premium over standard fixed-sight models in the collectors’ world.

In 1926 Colt paired down the D-frame slightly and offered the revolver with a 2" barrel chambered in .38 Spl. This was the famous Detective Special and became the mainstay for many plainclothesmen police officers throughout much of the 20th century.

Overall during its 88-year run, more than 750,000 Police Positive and Police Positive Special revolvers were made. The paradigm shift from revolvers to semi-automatic pistols fueled its demise in 1995. The Police Positive is one of the very few Colt revolvers not commanding an extraordinary premium today—except for the aforementioned target version. Nonetheless, it is a solid, accurate and serviceable revolver that doesn’t wear out the user who carries it daily, and in .38 Spl. still has enough punch to take the fight out of many bad guys.

Image from Wikimedia Commons, Michael E. Cumpston