The last Monday in May each year provides a moment when most Americans pause to think about people who are no longer with us. Sure, a visit to the beach or a cookout might be on the docket for the long weekend, but the message is still there despite the distractions: Memorial Day is our chance to turn our national attention to those who served and sacrificed—to those who answered the call and placed cause and comrades ahead of self. It is the time to reflect on the men and women who laid the costliest sacrifice at the altar of freedom.

As we look back 72 years to the last Monday in May 1944, the U.S. First Army was about to go to war. At camps and air bases across southern England, it was in the final stages of preparation for the D-Day invasion. On June 6, First Army would send a force of over 70,000 U.S. troops into combat in terrain dominated by beaches, canals and dense hedgerows. During the opening days of this battle, seven U.S. Army divisions were locked in intense combat, one of which was the 82nd Airborne. Although it committed three full parachute infantry regiments to the fight, part of the division traveled to France by glider, and that part would eventually make an enormous contribution to the campaign.

Men of the 325th Glider Infantry/82nd Airborne Division prepare to

board British-made Horsa gliders at an airfield in England.

From the very start of the invasion, the 82nd Airborne Division was heavily engaged with enemy forces primarily in the area between the town of Ste.-Mère-Église and the Merderet River crossing at La Fière. By D+2 (June 8), the division was in a tenuous position: with the German 91st Division swarming the hedgerows throughout the area, a stalemate had descended across the battlefield. U.S. forces were holding the east bank of the river at La Fière, and the Germans were holding the west bank at the settlement of Cauqigny. But the tactical situation for the 82nd Airborne was made all the more complicated by the fact that two pockets of paratroopers were trapped on the German side of the Merderet, and they could be overrun at any time. In the interest of cracking the impasse and relieving the two surrounded pockets, it was decided that the 1st Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry Regiment would cross the inundated area of the Merderet using a submerged stone road in a flanking maneuver that, it was hoped, would drive the Germans out of Cauquigny. The 325th had come in by glider beginning at 7 a.m. on D+1 (June 7) and had not by that point been committed to heavy action.

That night, the battalion successfully negotiated the swollen river crossing and, during the pre-dawn hours of June 9, engaged in a brief exchange of gunfire with Germans at the "Gray Chateau"—a stone manor house dominating the area. A small detachment from the battalion remained behind to neutralize the German force in the chateau while the rest of the battalion continued on, although much delayed by what had happened. Thereafter, the glider infantrymen linked up with one of the groups of surrounded paratroopers and prepared to assault Cauquigny at daybreak.

But the push toward Cauquigny ran into problems from the start. One column of troops became disorganized in the darkness, fragmented, and could not join the attack. Although lacking this additional firepower, the men of 1st/325th nevertheless began their assault before first light. Moving south, the battalion at first advanced steadily toward the north side of Cauquigny against sporadic resistance, but as the sun began to rise, the German defenders quickly organized themselves.

The counterattack that followed overwhelmed the inexperienced American glider infantrymen by sheer numbers. German infantrymen swarmed out of the hedgerows around Cauquigny and smashed into the men of 1st/325th. The numerically superior German force quickly pushed them back with torrents of small arms fire from Kar98k rifles and MP40 sub-machine guns. In addition to that, concentrated automatic weapons fire from MG42s was directed at the glider infantrymen, and in the face of that kind of firepower the men of the 1st Battalion/325th could not maintain the momentum of the advance.

The weight of the German counterattack was so great that the battalion faced certain annihilation. For that reason, the 1st/325th began a tactical withdrawal: pulling back to avoid disaster. This put one squad from the 325th’s C Company in a particularly disadvantaged position. This squad had penetrated an outer perimeter of defending riflemen and machine guns during the first phase of the assault, and was still moving to outflank Cauquigny when the German counterattack struck. The direct result of its’ far forward position was that this squad was cut-off as the rest of C Company fell back to the north. Pinned-down, the isolated squad of glidermen sought cover in a shallow ditch 400m southwest of Cauquigny.

Hostile fire was being directed at them by rifles to the left in the direction of Cauquigny, and from a machine gun in a farm compound 168m to their front. Although the men were temporarily safe from that machine gun, the position in the ditch was far from perfect because they could not move. Their only hope was to fall straight back to the north without delay, but there was one complicating factor that interfered with that move, and it was a major one: the hedgerows limited their options. In order for the squad to pull back to a safer position, each man would have to filter through a break in the hedgerow, cross a road, and then pass through another break in another hedgerow. It was obvious to the men of the squad that, because the Germans had so many troops and weapons in the area, any such movement would be greeted by a swarm of bullets. The situation had become absolutely critical for the small band of glider infantry.

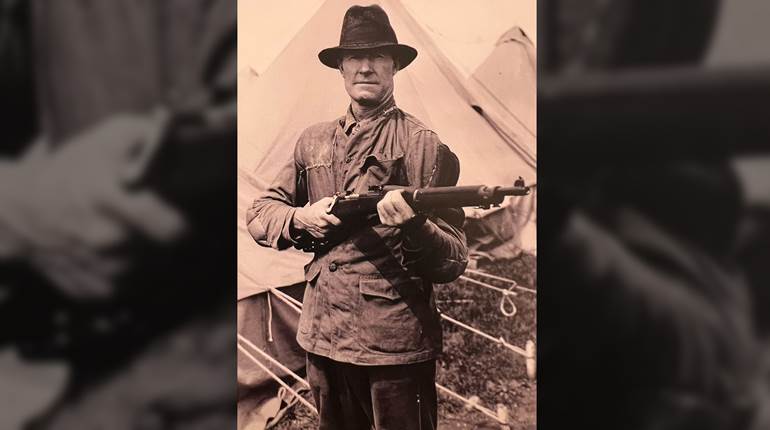

PFC Charles N. DeGlopper was one of the men in that squad. A 23-year old native of Grand Island, N.Y., DeGlopper was big: 6', 6" tall, 240 lbs. with size 13 feet. He had the perfect bulky and powerful stature for hefting the considerable weight of the weapon he carried: the 19.4-lb. M1918A2 Browning Automatic Rifle. Where such a weapon would have exhausted a soldier of slighter build, DeGlopper could carry the BAR with relative ease. The only problem was that his size also made him an easy target. Detecting the danger associated with making a dash for the break in the hedgerow, PFC DeGlopper volunteered to support the withdrawal of the squad with fire from his BAR. He obviously reached the sober realization that the only way his comrades stood a chance was if someone were to draw the enemy’s fire while they made their escape. Unhesitatingly assuming that responsibility, DeGlopper shouted to the others to go and that he would cover them. After that he went to work.

"Scorning a concentration of enemy automatic weapons and rifle fire, he walked from the ditch onto the road in full view of the Germans, and sprayed the hostile positions with assault fire."

The M1918A2 Browning Automatic Rifle—the weapon DeGlopper used during his Medal of Honor action at Cauquigny on June 9, 1944.

Shouldering his BAR in the open, the big 23-year-old instantly attracted the enemy’s attention. German fire was directed at DeGlopper from several different sources and within moments, he was hit. Ignoring his wound, he remained on his feet and continued firing at the enemy. Then, DeGlopper was hit by German bullets again and began to stumble. Although he dropped to one knee, he steadied himself and then amazingly still found strength enough to load a fresh 20-round magazine into his BAR, and then level it at the enemy one last time. Weakened by his grievous wounds, he continued to fire burst after burst at the Germans while the men of his squad fell back through the break in the hedgerow and across the road. While still kneeling in the middle of the road, a burst of concentrated gunfire finally killed DeGlopper outright. By drawing the enemy’s fire, he had saved the lives of all of the men of his squad. In the spot where he made his stand, his comrades later found the ground “strewn” with dead Germans. DeGlopper was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for what he did that morning at Cauquigny.

For decades, historians and tour guides used to say that Charles DeGlopper’s was the only Medal of Honor received by a soldier of the 82nd Airborne Division during the Normandy campaign. Then in March of 2014, that changed when 24 Jewish American and Hispanic American veterans from World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War were upgraded from lower awards. Among them was Private Joe Gandara, an M1919A4 machine gunner with D Company, 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment. His Medal of Honor action took place just a few hours after and a few hundred yards away from where Charles DeGlopper sacrificed his life earlier in the day. Gandara’s citation reads much like DeGlopper’s:

"When his detachment came under devastating enemy fire from a strong German force, pinning the men to the ground for a period of four hours, Private Gandara advanced voluntarily and alone toward the enemy position. Firing his machine gun from a carrying position as he moved forward, he destroyed three hostile machine guns before he was fatally wounded."

Like Charles DeGlopper, Joe Gandara knowingly sacrificed his life in the hedgerows around Cauquigny on June 9, 1944 and, like DeGlopper, he did it to save the lives of his brothers in arms. Within days, both men were buried at the temporary U.S. Military Cemetery at Blosville just 3.5 miles southeast of where their lives ended. Then in 1948, their remains were exhumed and moved to the U.S. Military Cemetery on Omaha Beach. During the 1950s, both of their families chose to have them returned to the U.S.A.

Today, Charles DeGlopper remains buried in Maple Grove Cemetery in his hometown of Grand Island, N.Y., and Joe Gandara is buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in Santa Monica, Calif. Although they may have come from different backgrounds, and although their graves are separated by 2,205 miles, the fate of war brought them together in a tiny Norman village on Friday, June 9, 1944. Under similar circumstances and with Medal of Honor citations that are very much alike, they brought honor upon themselves through self-sacrificing actions that saved the lives of others. The last Monday in May is their day: one man glider infantry—one man parachute infantry—both men the pride of the 82nd Airborne Division.