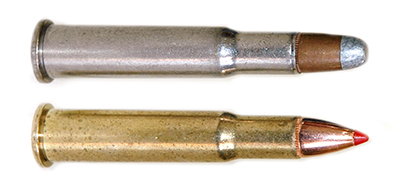

This illustration reveals the inner construction of some of today’s best-known bullets in .30 caliber and demonstrates how today’s big-game hunter has a variety of choices in projectiles that meet a wide range of performance requirements.

America’s hunters are passionate about their bullets. And they should be, because ultimately it’s the bullet that does the work of taking down game. This is nothing new. The jacketed bullet was a parallel and enabling development along with smokeless powder in the late 1880s because the lead bullets used for centuries couldn’t handle the new propellant’s unprecedented velocity. By the mid-1890s, it was learned that a bullet could be made to upset—expand or “mushroom”—by exposing some of the lead core at the nose. As velocities gradually increased toward 3000 f.p.s. in the 1910s, it was also discovered that the early jacketed soft-points were erratic in performance, all too often coming completely unglued on impact.

Hunters handled this problem differently. Doing most of his hunting before World War I, W.D.M. “Karamojo” Bell wrote that the barrel of a favorite .275 (7x57 mm Mauser) was never “polluted by the passage of a soft-nosed bullet.” In his youth, Elmer Keith returned to large-caliber blackpowder single-shots for a time, but throughout his long career consistently touted heavy-for-caliber bullets as a hedge against poor performance. Fortunately, expanding bullets got better between the two world wars. Thicker jackets and the amount of exposed core made a difference. So did mechanical devices such as Remington’s Core-Lokt, introduced in 1938, and Hornady’s InterLock, in 1939, which helped hold jacket and core together. The Nosler Partition, dating back to 1948, was a landmark achievement then and remains a good bullet today—a “dual core” concept with the two cores separated by a wall or “partition” of jacket material.

When I was a kid, we shot Core-Lokts and Winchester Power Points and Federal Hi-Shoks in factory ammunition, and if we handloaded, we used mostly the Interlock, Speer Hot-Core and Sierra GameKing. Sometimes, for something special, we sprung for the pricier Partitions. Most of the time, we did pretty well; who knows how many millions of deer and elk fell (and continue to fall) to these bullets. Today, though, we have a lot more choices. So many, actually, that it’s a bit confusing. As it was in the “old days,” we all have our favorites; but let me state a simple fact: There are so many bullets out there today that nobody can claim more than passing knowledge of all of them.

Also, although we tend to have strong opinions regarding bullet performance, and our campfire arguments often get heated, the reality is that most of us bring limited first-hand experience to the campfire circle. If anything goes wrong, we are quick to blame the bullet. (After all, it couldn’t be shot placement, could it?) If a recovered bullet isn’t beautiful, we’re quick to howl. But here’s the deal: If an animal is hit and not recovered, we cannot know exactly what happened. Was it poor bullet performance, or was it bad shot placement? Maybe either, possibly both. And if a bullet is recovered from game, then perhaps we should ask the question my old friend Chub Eastman often asked when he was handling customer relations for a bullet company: “At exactly what point in the death of the animal did the bullet fail?”

CONCEPTS

Now let me state three principles that haven’t changed for a century. First, velocity is the blood enemy of bullet performance. A given bullet that performs wonderfully in the 7 mm-08 Rem. may become an unreliable bomb in the 7 mm Rem. Ultra Mag. This works the other way, too: Really tough bullets that expand well at high velocity may not expand at all “way out there” where velocity has decreased.

Second, bullet expansion is the enemy of penetration. The more a bullet expands, the greater resistance it encounters. This isn’t bad, it’s just true. Bullet expansion creates a larger wound channel, doing more damage. Varmint bullets are designed to be very frangible, literally coming apart on impact. This reduces ricochet and is desirable for explosive effect on non-edible pests. Big-game bullets, on the other hand, must hold together well enough to penetrate into the vitals. Obviously, the requirement is different for an elk than for a pronghorn, and on the world’s largest game (elephant, hippo, rhino) we use non-expanding “solid” bullets to guarantee the greatest penetration possible. With expanding bullets, some are designed for limited expansion and maximum penetration, while others are designed to expand rapidly and radically.

You can’t have it both ways: Expansion limits penetration. There are two schools of thought in play. Some hunters want through-and-through penetration, arguing that exit wounds leave a better blood trail to follow. Others prefer the bullet to stay inside the animal, arguing that energy expended on rocks and trees on the far side of the target is wasted. Those who want penetration will gravitate toward tougher bullets that retain much of their weight and expand less. Those in the other school demand penetration at least into the vitals, but seek more expansion and will probably accept a bit more weight loss. Their ideal is to recover the bullet “against the hide on the far side.”

There is merit to both schools of thought. Personally, I’ve come full circle. In my younger days I wanted full penetration. Today I’m not so sure. Exactly how an expanding bullet transfers energy during its passage remains a bit mysterious. However, while it’s absolutely true that the trail left by a bullet that exits is easier to follow, I think it’s equally true that you’ll do less tracking when an animal is shot with a bullet that creates a larger wound channel through the vital organs and expends its energy during its passage.

Third, bullet weight covers a lot of sins in bullet performance. This, of course, was Elmer Keith’s mantra. He wasn’t altogether wrong. A 180- or 200-gr., .30-cal. bullet of simple construction may shed some weight at higher velocities, but it can afford to shed more weight than a 150-gr. projectile of the same caliber. Without pretending to do the impossible—meaning cover all of today’s hunting bullets—let’s talk about some basic design concepts.

SHAPE

When the tubular-magazine lever-action was king, most hunting bullets were either flat-pointed or round-nosed. Today most of us use sharp-pointed bullets, spitzers, because they are more aerodynamic and thus retain velocity better. But not everybody needs a bullet that retains velocity well. In fact, millions of deer hunters don’t. Savvy big-woods hunters know that blunt-nosed bullets tend to deal a heavier blow on impact than a sharp-pointed bullet. No doubt remembering that principle, Remington’s 75th anniversary of the Core-Lokt (1939-2014) featured a good old 180-gr. round-nose .30-’06 Sprg. load. That isn’t a 300-yd. load, but a lot of folks don’t need a 300-yd. load. In general, however, most of us shoot spitzers.

These days, with long-range shooting all the rage, bullet aerodynamics are improving and ballistic coefficients (BCs) are going up. More about that later, but, more than ever, boattail bullets are “in.” Okay by me, I shoot a lot of boattails, but keep in mind they were developed before World War I for extreme-range “plunging” machine gun fire. At long range you need all the help you can get. But at the normal ranges practical for most of us, the actual difference in trajectory between a boattail and a flat-based bullet is insignificant.

Boattails do have one drawback: Absent some of the design features we’ll talk about, the boattailed base does have a tendency to squirt the core out of the jacket. It isn’t uncommon to recover a boattailed jacket with the core entirely missing. This is not as significant as some folks make it out to be, as it usually happens at the very end of penetration, when the bullet is slowing to a stop and tumbling. You can generally assume that the core is somewhere nearby; because, absent the core, the light, expanded jacket is incapable of much penetration.

CUP AND CORE

The simplest expanding bullets are created by a series of dies that draw a copper disk into a cup that is then filled with a lead core. We have already named several of these bullets. Expansion and weight loss can be somewhat controlled by the jacket’s thickness, alloy composition and the amount of exposed core. Also, some have mechanical features that aid in locking the jacket and core together. The primary advantages to simple cup-and-core bullets are that they are inexpensive to make and, perhaps, the easiest of all designs to make extremely accurate. Cup-and-core bullets may have open tips, as in many varmint and match bullets, or traditional exposed lead tips. All will offer significant, and sometimes violent, expansion.

In these days of “designer bullets” the disadvantage, as such, is that these bullets, if recovered, often aren’t very pretty. At least some, and often considerable, weight will be lost as part of the lead core “wipes away” during penetration. Keep in mind that pretty is as pretty does. I tend to like “plain old bullets,” or POBs as I refer to them, especially for deer hunting and often, because of accuracy, even for mountain hunting. Reliable bullet expansion is not a bad thing, so long as you can absolutely get penetration into the vitals from any reasonable shot angle. This is somewhat controlled by bullet weight and caliber, and also by velocity, as previously explained. Examples: I had a .300 H&H Mag. that just loved Sierra GameKings. For deer and sheep I used a 150-gr. bullet; for larger game I used a 200-gr. bullet. Another favorite “POB” is the Hornady InterLock. With a 180-gr., .30-cal., I’ve used it all over Africa in .30-’06 Sprg., and have always experienced consistently outstanding performance. I’ve used the same bullet in .300 Wby. Mag. to hunt mountain game. But, since ranges average farther, impact velocities for that faster cartridge are probably similar, and performance has remained consistent.

TIPPED

Nosler’s Ballistic Tip, introduced in the early ‘80s was probably the first modern bullet with a polymer tip. Today, almost every manufacturer offers “plastic-tipped” bullets, but the concept isn’t new. Remington’s old Bronze Point, dating to the 1930s, was probably the first “tipped bullet,” and, in the 1960s, the Canadian Sabre Tip from C.I.L. was probably the first plastic-tipped bullet. With tips in a wide variety of colors, the tipped bullet looks sexy and doesn’t batter in the magazine like an exposed lead tip.

Just keep this in mind: Upon impact, the tip is driven down into the bullet, initiating and often expediting expansion. So, absent additional design features such as core-bonding or homogeneous construction, the tipped bullet will usually expand radically, and probably won’t be gorgeous when recovered. The old Bronze Point was one of Jack O’Connor’s favorites for deer and sheep, but many thought it expanded too quickly. Today, exactly the same can be said of simple tipped bullets such as the Ballistic Tip and Hornady’s SST. Rapid expansion and weight loss is somewhat mitigated by jacket thickness and always by bullet weight and velocity, but some will love them and others will judge them too volatile. Again, I have no issues with bullet expansion provided the vitals can be reliably penetrated. So I find this type of bullet decisively effective on mid-size game such as deer, pronghorn and sheep, but I prefer a tougher bullet for larger game.

BONDED

Chemically bonding a bullet’s core to its jacket allows for fairly dramatic expansion without weight loss. Essentially handmade, Bill Steiger’s Bitterroot Bullet, another 1960s development, was probably the first bonded-core bullet, legendary though relatively unavailable. Jack Carter’s Trophy Bonded Bearclaw, developed in the early ‘80s and long made under license by Federal, popularized the legend. Today, most manufacturers offer a bonded-core bullet. Examples include: Federal’s Trophy Bonded Tip, Hornady’s InterBond, Norma’s Oryx, Nosler’s AccuBond, Remington’s Core-Lokt Ultra, Swift’s A-Frame and Scirocco, Winchester’s Power Max Bonded, and more. Some expand more than others, and some tend to be more accurate than others. In general, although some rifles always seem to defy the rules, the bonded-core bullet is usually not the most accurate choice. And because it is complex to make, it will also always be more expensive. Because core-bonding allows radical expansion, the bonded-core bullet may not be the deepest-penetrating design, but since it retains the vast majority of its weight during penetration, it can be considered a good combination of expansion and penetration. If you prefer to recover good-looking bullets “against the hide on the far side” you will probably like the bonded-core bullet.

Of course, various design features can be combined. Some bonded-core bullets, such as the original Bearclaw, Core-Lokt Ultra and Oryx, have exposed lead tips. Many have polymer tips, including the AccuBond, InterBond, Scirocco and Trophy Tip. Winchester’s Power Max Ultra has a hollow point in front of a bonded core. Swift’s legendary A-Frame, probably the most complex hunting bullet to manufacture, is a dual-core bullet, the two cores separated by a wall of jacket material, with the front core bonded to the jacket. Though costly, the A-Frame probably has the highest weight retention of all lead-core bullets, as high as 98 percent.

HOMOGENEOUS

The Barnes X was the first successful commercial expanding bullet made entirely of copper alloy—with no lead core. Today there are several, including Barnes TSX (Triple Shock eXpanding) and TTSX (Tipped Triple Shock eXpanding), Federal’s Trophy Copper, Hornady’s GMX (Gilding Metal eXpanding), Nosler’s E-Tip and Winchester’s Razor Boar XT. Most such bullets today have polymer tips, but all expand because of a skived nose surrounding a nose cavity. The homogeneous-alloy, or monolithic, projectiles are all “penetrating” bullets. Expansion is limited by the depth of the cavity, and is generally less than the expansion of lead-cored bullets. Upon impact the nose splays into petals. The only way the homogeneous bullet can shed weight is by having petals shear off. This can happen, but weight retention can be almost 100 percent when all petals remain.

As with all bullets, some rifles will group extremely well with these bullets and some will not, but early issues with copper fouling and finicky accuracy have been solved by driving bands. Lacking a lead core, these bullets tend to be long for caliber, so cartridge overall length can be an issue with some actions. This is mitigated by the simple fact that these bullets break the rules. They hold together so well that less initial weight is needed to ensure penetration. If you like exit wounds you will love them, but you won’t often recover them. One drawback might be simply that, as a design feature, expansion is limited, but that’s not a drawback if you prefer penetration above all else. An actual drawback is that, like all bullets, expansion is reduced as bullet speed drops, so these bullets are generally not ideal for long range.

THE NEW FRONTIER

Whether I agree with extreme-range shooting at game doesn’t matter. The current fascination with long-range shooting is driving manufacturers to produce bullets that are more aerodynamic and that expand reliably across a greater velocity spectrum. Walt Berger’s match bullets have long been legendary for accuracy, but Berger’s VLD is an anomaly, a hollow-point bullet intended for big game. I have found them to be excellent at longer ranges, but volatile when close range is combined with high velocity. A Berger specialty has long been high BCs, and they offer a wide range of bullet weights, including extra-heavy bullets in the more popular calibers.

Thanks to the magic of computer-aided design, bullet aerodynamics can be enhanced. This is a primary point to Nosler’s new ABLR (AccuBond Long Range) line, coupled with expansion across a wider velocity range. This is one bullet with which I have zero field experience, but that is clearly from a long-proven product line, and Nosler is a time-honored name.

Some years back, Hornady revolutionized ammunition for tubular-magazine lever-actions with its FTX (Flex Tip eXpanding) bullet, which featured a “squishable” polymer tip that, for the first time, allowed safe use of cartridges carrying aerodynamic spitzer bullets in a tubular-magazine gun since the rounds’ soft points couldn’t detonate the primers of the cartridge ahead of them under recoil. That isn’t new, but it suggests that not all polymer tips are equal. Just now released is a brand new Hornady development, the Extremely Low Drag-eXpanding, or ELD-X (January 2016, p. 66). Initial design criteria were maximum flight characteristics and extreme accuracy, plus consistent expansion across a wider velocity spectrum. Using Doppler radar to track bullet speeds (and thus establish true BCs), company ballisticians discovered some anomalies. Something was changing during flight. The only thing it could be was the polymer tip changing shape. After going back to the drawing board (for years), they came up with a final result having a tip of different material that remains inert during flight.

At this writing, the ELD-X is probably the world’s newest hunting bullet. I have not experimented with it at extreme range, but I did use it in Africa last year in a 180-gr., .300 Win. Mag. load. Expansion seemed very consistent from up close to 450 yds. (the longest shot I took), but one thing I did notice: Beyond 300 yds. my data for a 180-gr., .30-cal. at that velocity was off, with all strikes a bit high. So bullet development continues, but the new frontier is almost certainly enhanced long-range performance.