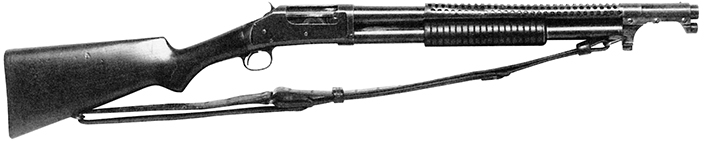

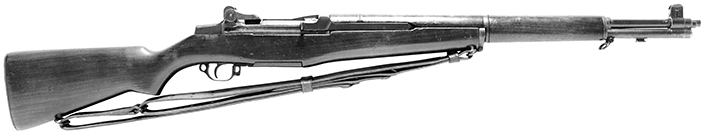

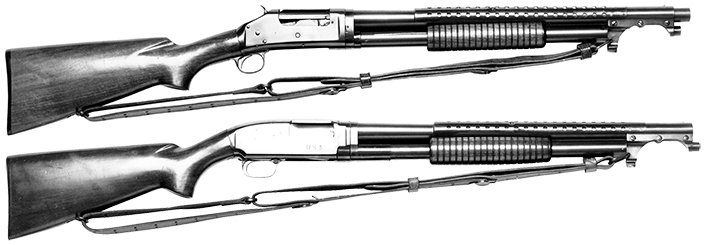

(From top) Winchester U.S. Cal. .30 M1, Winchester U.S. Cal. .30 M1 Rifle, Winchester U.S. Model of 1917 Rifle, Winchester U.S.-issue World War II , Winchester U.S.-issue World War I Model

This article was first published in American Rifleman, August 1999

Few arms makers are as well known as the Winchester Repeating Arms Co. The guns turned out by the venerable New Haven, Connecticut, firm have enjoyed a great deal of popularity with collectors and firearms enthusiasts for several generations. While the firearms produced by Winchester are indisputably an integral part of the American culture, guns produced by the firm for the United States military are often all but forgotten. Winchester was a major supplier of small arms and ammunition to the U.S. military during the 20th Century, and the company’s contribution in this area is possibly unequaled.

The forerunner of the Winchester rifle was the Henry. During the Civil War, some Union outfits utilized privately purchased Henrys, and a small number were procured under contract by the government. In 1866, the fledgling Winchester Repeating Arms Co. was organized and the Model1866 rifle was introduced. The Model 1866 was essentially a greatly improved Henry rifle, and it soon proved popular with those heading West. Though popular among civilians, the U.S. military never warmed to the idea of lever-action military arms. In fact, the only lever-actions adopted by the U.S. in the 19th Century were a small number of .30-40 Gov’t-cal. U.S. Model 1895 Rifles and Carbines. Though Winchester produced bolt-action .45-70 Gov’t-cal. Hotchkiss repeaters and Model 1895 6 mm Lee Navy straight pulls under contract, large, lucrative U.S. government contracts eluded the firm until the United States entered World War I.

U. S. MODEL OF 1917 “ENFIELD” RIFLE

As the clouds of war began to gather over Europe in 1914, most American arms makers were deluged with orders from friendly governments. Great Britain contracted with three U.S. companies, Winchester, Remington and Eddystone (an affiliate of Remington) for production of its newly adopted Pattern of 1914 rifle. The P’14 was a modified Mauser action that was initially to have been chambered for an advanced .276-cal. cartridge and was slated to replace the venerable Lee-Enfield rifle. The realities of wartime resulted in the design being changed to accommodate the standard .303 British cartridge in order to simplify supply problems.

By the summer of 1916, P’14 rifles were flowing from the three American plants, and the contracts were just being completed when the United States declared war on Germany and its allies. The U.S. military was immediately faced with a serious shortage of the standard M1903 rifles and the Ordnance Department scrambled to find a new source. Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal were already gearing up to operate at peak capacity to produce M1903s, but their combined production would be far short of requirements. It was briefly considered to have civilian manufacturers tool up to produce the M1903, but the time required to get into production would result in a crippling shortage of rifles. The decision was soon made to adopt the British-designed P’14 rifle but slightly modify it to accept the U.S. .30-’06 Sprg. cartridge. This modification could be accomplished without a great deal of difficulty, and the rifle was standardized as the “U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, Model of 1917.” The United States also adopted the British P’14 bayonet and gave it the same “Model of 1917” designation.

Since the manufacturing facilities and work force that had successfully produced the P’14 were still in place, large numbers of M1917s were soon flowing. All three makers turned out a total of 2,422,529 M1917 rifles by the time production ceased in early 1919. Of this total, Winchester accounted for 465,980 M1917 rifles and bayonets.

The M1917s were finished in bluing and were stocked with a good grade of walnut. The name of the manufacturer, designation and serial number were stamped on the receiver ring and the initials of the maker and date of production were stamped on the barrel. Most parts were also stamped with the initials of the maker (“W”, “R” or “E”). As originally assembled, all Winchester M1917 rifles used “W”-marked parts.

The M1917 soon became the predominate rifle of the “Doughboys” of the American Expeditionary Force in France during World War I. Anyone doubting the M1917’s suitability as a combat rifle should realize that the most famous Doughboy of them all, Alvin C. York, used an American Enfield when he performed the amazing feat of arms that earned him the Medal of Honor.

Following the Armistice, the M1917 was retired to the war reserve stockpile and the ’03 remained standard issue. Most of the M1917s in the government’s inventory were refurbished and issued for training use and as supplementary service rifles during World War II. In 1945, they were declared obsolete and large numbers were sold to NRA members through the government’s Director of Civilian Marksmanship Program. Many were subsequently sporterized, and unaltered examples remaining in their original 1917-1918 factory configuration are surprisingly scarce today.

While not a “home-grown” design, the M1917 provided valuable service to the armed forces and was an example of how Winchester, along with other civilian arms makers, turned out vast quantities of small arms under difficult circumstances.

MODEL 1897 12-GA. “TRENCH GUN”

The unique nature of trench warfare during World War I required the use of new and sometimes innovative arms. One of the more interesting of this type was the “trench gun.” For many years it was well known that a shotgun loaded with buckshot could be devastating at short ranges. During the Philippine campaigns around the turn of the century, several hundred John Browning-designed Winchester Model 1897 12-ga. riot shotguns were purchased by the Army for use in battling fierce Moro tribesmen.

General Pershing and other high-ranking officers had previously witnessed the shotgun’s effectiveness in the Philippines and supported the development and fielding of a combat shotgun in World War I. The proven Winchester Model 1897 was selected.

The Ordnance Department mandated that such a shotgun must be capable of mounting a bayonet. Also, some means of protecting the hand from a hot barrel while wielding the gun during bayonet fighting was required. A unique ventilated metal handguard with an attached bayonet adapter was jointly developed by Winchester and Springfield Armory. It was designed for use with the M1917’s bayonet.

The U.S. government ordered 19,196 “trench guns” from Winchester in 1918. Several thousand more were believed to have been converted from existing commercial production Model 1897 shotguns. Some long-barrel Model 97s were also procured for use in training aerial gunners. A quantity of plain-barrel riot guns were also procured during this period. A much smaller number of Winchester’s newest shotgun, the Model 12, was also acquired in trench, riot and training variations.

Following preliminary field testing, the Model 1897 trench guns were issued to front-line combat units. Under close-range conditions, the shotguns proved awesomely effective. So much so that the German government lodged a formal diploma-tic protest against the United States’ use of shotguns and threatened to execute any American soldier captured with a shotgun or shotgun ammunition (A rather novel act for the nation that introduced poison gas into warfare—The Eds.). The American government responded forcibly to this protest and stated that severe reprisals would be taken if the Germans carried through on their threats. Apparently this response resulted in the German government backing down, and the American military continued to issue shotguns for combat use as fast as production and shipping allowed right up to the time of the Armistice.

The military trench guns remained in inventory following the war and saw a fair amount of use in the 1920s and 1930s by the Army and Marines.

M1 Garand Rifle

In 1936, the Army adopted the famed M1 “Garand” rifle that was developed by John C. Garand, a civilian employee of Springfield Armory. The semi-automatic M1 was adopted when other nations still firmly clung to bolt-action rifles. The M1 was chambered for the standard .30-’06 Sprg. cartridge and fed from a sheet-metal eight-round “en-bloc” clip.

Production at Springfield Armory was initially very slow due to the change in tooling from the ’03 rifle, a change in the new Garand’s gas system and a lack of tremendous demand. By late 1939, however, it was becoming obvious that production of the M1 would have to be substantially increased. Plans were made to boost production at Springfield Armory, but a secondary source of M1 production was desirable. On April 4, 1939, Winchester was granted an “Educational Order” for 500 M1 Rifles and production tooling. The first Winchester M1s were delivered in December 1940. Even while Winchester was in the process of producing the “Educational Order,” the government ordered 65,000 additional rifles from the firm. These so-called “Second Contract” rifles were delivered between April 1941 and May 1942. As World War II progressed and the demand increased, additional M1 orders were given to Winchester. By the time contracts were canceled in June 1945, Winchester had produced 513,880 M1s.

As M1 rifle production continued, specifications were changed on many parts to speed manufacturing time or reduce costs. Interestingly, fewer of the later-pattern parts were found on Winchester M1s as compared with those made by Springfield Armory. This is because Winchester was a commercial firm, and any changes had to be negotiated with the company and additional compensation paid. Many parts of Winchester M1s remained unchanged until very late production (if at all) while newer vintage parts had been used by Springfield for several years.

The final variant of the M1 rifle made by Winchester is known today as the “WIN-13” due to the drawing number on the receiver. This “WIN-13” variant is unusual in that the serial number range is lower than rifles made by Winchester several years earlier. The “WIN-13” rifles were in the 1,600,000 to 1,640,000 range. Unlike earlier Winchester M1s, many of the “WIN-13” rifles were fitted with a number of later-vintage parts. Curiously, however, “WIN-13 rifles made very late in the production run often contained a mixture of early- and late-vintage parts. This was due to the sensible practice of using up any and all parts on hand when production contracts were canceled.

The name of the maker, model designation and serial number were marked on the receiver behind the rear sight. The barrel was marked “W.R.A” under the handguard and the right side of the barrel was stamped with the familiar intertwined “WP” (Winchester Proofed) logo. The left side of the stock was stamped with a cartouche consisting of “WRA” and the initials of the Head of Winchester’s Hartford Ordnance District. The most common cartouche was “WRA/GHD” (Winchester Repeating Arms/Col. Guy H. Drewry). The first cartouche contained the initials of Col. Robert Sears (“WRA/RS”) and the second variety had the initials of Col. Waldemar Broberg (“WRA/WB”). Two distinct types of “WRA/WB” cartouches may be found. All types of cartouches were stamped next to the Ordnance Department “crossed cannons” escutcheon indicating that the rifle had passed all requisite inspections and been accepted into government service. As was the case with Springfield Armory M1s, pistol grips were stamped with a circled “P” mark indicating that they had been successfully proof fired. World War II Winchester Garand barrels were not marked with the date of manufacture.

Most components were marked “WRA” to indicate that they were produced by Winchester. Most metal components of the M1 rifle were Parkerized but a few smaller parts were blued.

The Winchester M1s provided valuable service to U.S. troops, and after the war, most were overhauled by several ordnance facilities and fitted with new replacement parts. Very few Winchester M1s survive intact today and the majority have been rebuilt and will have few, if any, Winchester parts other than the receiver. Winchester did not resume production of the M1 rifle following World War II.

U.S. .30 CALIBER M1 CARBINE

Just prior to the America’s active involvement in World War II, a unique design by the Winchester firm was adopted: the M1 Carbine. It was destined to be manufactured in greater numbers than any other U.S. military arm in history.

The development of the M1 Carbine had its roots back in the trenches of France in World War I when a few .351-cal. Winchester Self-loading Rifles were informally tested. The compact and lightweight SLR was viewed as an almost ideal rifle with which to arm troops not assigned directly to front-line combat duty. The typical service rifle of the day was too heavy and cumbersome to be utilized by Signal Corps troops, crew-served weapons personnel and other generally non-combatant soldiers. Such troops were usually armed with handguns that were essentially useless beyond any but point-blank ranges. While the development of a “light rifle” was shelved with the Armistice, it was again resurrected when German Blitzkrieg tactics rendered the old concept of fixed front lines as a thoroughly outdated doctrine. Troops usually considered as non-combatant could be engaged by airborne or rapidly moving mechanized hostile forces with little or no advance notice. A short, lightweight and rapid-firing rifle was seen as ideal for such use.

In June 1940, the War Department issued a requirement for such a rifle, and designs were solicited from private inventors and arms makers. An Ordnance Department board was established to evaluate the submissions. Prior to selecting a design, the Ordnance Department decided to base the cartridge for the proposed new “light rifle” on a .30-cal. version of the Winchester .32-cal. SLR round. The government ordered a quantity of the new ammunition from Winchester for use in testing guns submitted for consideration. None of those initially submitted were deemed acceptable, and a second round of tests was scheduled for September of 1941. Winchester did not plan to submit a design due in large part to the burdens of getting the M1 rifle into mass production. With some high-level unofficial encouragement from the Ordnance Department, Winchester submitted a “light rifle” design based on a short-stroke gas piston. By working literally around the clock, Winchester was able to field an entry for the second round of testing. After the grueling competition, the Winchester design was selected for adoption as the “U.S. Carbine, Caliber .30, M1.” It weighed just over 5 lbs. and fired its .30-cal. cartridge semi-automatically at a muzzle velocity of 1970 f.p.s. The carbine utilized a detachable, 15-round box magazine. Soon after adoption, the government purchased the manufacturing rights from Winchester for $886,000.

Eventually, nine other commercial firms were given production contracts to produce M1 Carbines. When all contracts were canceled in 1945, 6,221,220 had been manufactured. Winchester produced some 828,059, or about 131⁄2 percent of the total. Winchester M1 Carbines were marked with the name of the company behind the rear sight. Each prime contractor was assigned a code letter. Winchester’s code was, logically, “W.” The barrels of very early Winchester M1 Carbines were marked “WRA” along with the month and year of production while later versions were simply marked “W.” As was the case with all carbine prime contractors, Winchester acquired many components from a vast network of subcontractors. Most components were stamped with “W” along with the initial of the subcontractor that actually made the part. After the war, most carbines were overhauled and fitted with later parts, thus finding a carbine today with all original matching coded parts is quite uncommon. Except for late-production carbines, the right side of the Winchester stocks were stamped “WRA/GHD” beside a “crossed cannons” ordnance marking denoting final government acceptance.

There were many changes made to the M1 Carbine during its production run including modifications to the rear sight, stock, safety and most other parts.

Compared with the pistol, which it was originally designed to replace, the carbine possessed much greater range and accuracy. It was only unsatisfactory in these respects when compared to a rifle. When used as intended, the carbine was a very good arm and markedly increased the firepower of G.I.s during World War II.

The prime contractors did a remarkable job in turning out vast numbers of carbines despite ever-increasing demand. By late 1944, the production rate of carbines was such that most of the remaining contracts were canceled. Winchester and Inland were the only two firms to remain in production in 1945 and these two companies produced carbines until all contracts were cancelled just prior to V-J day. As was the case with the M1 rifle, the vast majority of M1 carbines were overhauled after World War II and fitted with later-pattern parts. During these widespread rebuild programs, most carbines lost their originality due to the replacement of original parts.

MODEL 97 AND MODEL 12 MILITARY SHOTGUNS

After Pearl Harbor, the nation’s military was in short supply of virtually all types of small arms. This was true of the well-used 1918-vintage combat shotguns in inventory, and contracts were given for new guns of this type. Along with Winchester, the Ithaca Arms Co., Savage Arms Co., Stevens Arms Co. and Remington Arms Co. received contracts for shotguns during World War II. Approximately 500,000 were delivered to the government during the war. Most of them were Winchesters.

As was the case during World War I, Winchester produced Model 97 and Model 12 shotguns under contract. Much larger numbers were produced and issued during World War II as compared with World War I. The World War II-contract Model 97 trench gun differed from the World War I version in several respects, the most obvious being that it was a take-down rather than solid-frame model. The ventilated metal handguard found on most World War II Winchester Trench Guns had four rows of holes rather than six rows as found on the World War I-vintage guns. While the World War I trench guns had hand-stamped martial receiver markings (“U.S.” and the flaming bomb symbol), the World War II Winchester trench guns had machine-stamped barrel and receiver markings. The top of the barrel was stamped with a flaming bomb symbol and the left side of the receiver was stamped with a “U.S.” and the flaming bomb. The stock was stamped with a cartouche and crossed cannons escutcheon. Early military shotguns were stamped “WB” on the stocks and later versions had “GHD” cartouches. World War II Model 97 shotguns were blued.

The Model 12 military shotguns were fitted with the same type of handguard/bayonet adapter as the Model 97 and had similar martial markings and stock cartouches. The Model 12 had a flaming bomb symbol stamped on top of the barrel and a “U.S.” and the flaming bomb marked on the receiver’s right side. Except for some very late-production trench guns that were factory-Parkerized, all World War II Model 12 shotguns were blued. In addition to the trench guns, some plain-barrel riot guns and longer-barrel training guns—both Model 97s and Model 12s—were purchased.

The Model 97 and Model 12 shotguns saw a surprising amount of use in World War II, primarily in the Pacific Theater—a U.S. Marine Division was authorized 306 combat shotguns. In addition to combat duties, some were also used for security duty and for guarding prisoners.

Following the conclusion of the war, the Model 12 officially remained classified as “Standard” although a number of Model 97s remained on hand as well. Many saw use during the Vietnam War.

After the war, large numbers of World War II shotguns were overhauled, which resulted in many being refinished by Parkerizing as part of the rebuild process. Surviving unaltered examples retaining the original factory bluing and cartouched stocks are highly prized by collectors today.

The arms of Winchester provided valuable service to our country’s armed forces throughout this century, and their role is sometimes overlooked. Despite the lack of attention paid to them by many collectors today, military Winchesters have earned their place in American and firearms history.