In the nuclear age that followed World War II, America’s fleet of long-range strategic bombers began operating over thousands of miles of uninhabited terrain. The newly independent Air Force designed its first purpose-built survival rifle in 1949. Designated M4, the magazine-fed bolt-action, manufactured by Harrington & Richardson, was chambered in .22 Hornet. The rifle featured a sliding wire stock and a barrel that screwed into place at an index mark on the receiver and was secured in place by a thumb screw. The M4 weighed 4 lbs. and disassembled into a two-piece package the size of its 13.5" barrel. A few years later, a second design was adopted. The M6 was an over-under in .22 Hornet/.410 that folded to the length of its 14" barrels and was manufactured by Ithaca.

As a division of Fairchild, ArmaLite had its eye on Air Force contracts. Within a month of establishment of the ArmaLite Division, the Air Force put out a call for a new takedown survival rifle. Among the requirements specified was that the new rifle would float. ArmaLite put its engineers on the project, and within a month the Air Force had a working prototype in its hands for evaluation. Following its protocol of naming new models, ArmaLite called it the “AR-5.”

Though it mirrored the M4’s bolt-action, .22 Hornet concept (an original ArmaLite photograph shows Eugene Stoner at his work bench with an M4 lying beside an AR-5 prototype), the rest was a radical new design. The centerpiece of the AR-5 was a hollowed-out fiberglass stock, which built on George Sullivan’s experiments with synthetic stock materials, into which the action and barrel could be stowed to make a compact package that would float in water. ArmaLite called it the “pack-in-stock” concept. Its 14" barrel attached to the aluminum alloy receiver with a threaded collar, a knurled-head bolt attached the stock to the receiver and the whole thing could be assembled without tools. It weighed 2 lbs., 8 ozs. and was slightly more than 14" long disassembled.

In 1956 the Air Force adopted the AR-5 as the MA-1. Flush with its first success, ArmaLite believed its new rifle had applications beyond a survival scenario, imagining the AR-5 in the hands of paratroopers or supplied to guerilla fighters behind enemy lines. But ArmaLite’s first success in selling one of its designs to the military was short-lived. As America’s defense strategy shifted from long-range bombers to intercontinental ballistic missiles, the need for the new survival rifle faded away. Although the Air Force considered the MA-1 a superior design, it deemed its existing stock of M4 and M6 rifles adequate for its needs (it had nearly 100,000 in inventory). Only about a dozen MA-1s are believed to have been acquired.

While not a sales success, the AR-5 boosted ArmaLite’s confidence that it could successfully design firearms for the U.S. military, and the company actively began pushing its AR-10 as America’s next battle rifle. But by 1959 the U.S. had decided to adopt the M14 instead. ArmaLite licensed its AR-10, along with a scaled-down version, known as the AR-15, to Colt’s Manufacturing. In five years, Fairchild’s firearm division had given almost no return on investment to its parent company. The ArmaLite management saw the writing on the wall. As L. James Sullivan, one of the company’s designers at the time, said, ArmaLite “had no reason for being and needed one.”

With the R&D of the AR-5 on its hands and no military market for the rifle, ArmaLite sought to take the design to a larger audience. The company claimed that reports of the AR-5 in the press resulted in a flood of letters asking for a civilian version of the rifle. Initially, ArmaLite considered lengthening the AR-5’s barrel to 16" for the civilian market. That plan was dropped, and it came up with a new design that used as much of the AR-5’s technology as possible.

Like all ArmaLite products, the new rifle would be a team effort. The company’s general manager, Charles Dorchester, ordered L. James Sullivan, fresh off of the AR-15 project, to be the engineer-in-charge of the new rifle based on a design layout by head of engineering Eugene Stoner (the AR-7’s “ornamental” patent was issued in Stoner’s name). Tom Tellefson, the company’s plastics engineer, designed the floating stock made out of a plastic known as Cycolac, while Sullivan made working prototypes and finalized the internal design. The result closely resembled the AR-5/MA-1 with its steel-lined aluminum barrel and hollow stock. Where the new rifle differed was in its operating mechanism. Sullivan’s action was simple. Instead of a bolt-action .22 Hornet, the new rifle was a blowback semi-automatic in .22 Long Rifle that fed from an eight-round magazine. It was the seventh model in the company’s history. ArmaLite called it the AR-7 Explorer.

Production of the AR-7 started in late 1959, and the first rifles shipped in July 1960. All of the AR-7’s components were made by subcontractors in the Los Angeles area and then brought in-house to be assembled, inspected and tested. Ten thousand AR-7s were manufactured in the first 18 months of production. It was the first ArmaLite product to be made in-house, and it was the company’s first design offered to civilians. ArmaLite had high hopes for the AR-7. By manufacturing the rifle itself, the company hoped that income generated by its sales would cover its operating expenses, provide the funds for R&D of new products and get the Fairchild bean counters off its back.

When introduced, the AR-7 cost $59.95. Its MSRP was quickly adjusted to $49.95, the same price as Remington’s Nylon 66, another futuristic plastic rifle introduced around the same time. Early ArmaLite ads touted its “Air Force Survival Rifle” featuring the “latest technology in exotic light alloys” that was “Light, Compact, Safe for Boat, Plane, Car.” The company also extolled the “handgun convenience” of the AR-7, emphasizing that the takedown design offered a pistol-size package in areas where handguns could not legally be carried or transported. In fact, with a little practice the rifle could go from stored inside its stock to assembled and ready to fire in about 30 seconds.

The AR-7’s popularity quickly spread beyond survivalists. The light and handy rifle was perfect for a day in the field or teaching a youngster to shoot. A later ArmaLite ad recommended the rifle for “hunting and plinking” and showed a mariner using his AR-7 to fend off a frenzy of sharks as his scuba-diving buddy scrambled into the safety of the boat.

The design caught the eye of Hollywood as well. Overnight, its unique takedown capability made the AR-7 the celluloid spy sniper rifle of choice, beginning with the 1963 film, “From Russia With Love” when Sean Connery’s James Bond pulls a brown-stocked AR-7 out of his tuxedo jacket and conveniently assembles it for the camera. In the movie’s climax, Bond uses the rifle to dispatch a pesky helicopter. ArmaLite actively marketed the AR-7’s first big-screen appearance, which caused an up-tick in sales.

The AR-7’s military heritage quickly lent itself to creative minds. Some of the most unique results came from the Hy Hunter Firearms Manufacturing Co., a Hollywood-based business that, in the early 1960s, repackaged the rifles to make them resemble an M1 carbine, a 1928 Thompson and even a Broomhandle-style pistol it called the “Bolomauser.” In some of the most optimistic marketing of the AR-7 ever printed, the company stated of the “T-62 Civilian Defense Carbine,” as the faux Thompson was known, “not only does this weapon look like the ‘Chicago Typewriter,’ but it has more potential firepower than any weapon since,” making it “the perfect weapon for civilian defense, house-to-house fighting, jungle warfare” and “repulsing enemy paratroopers.” The ad showed a faithful T-62, armed husband pointing his AR-7 skyward towards a Red Dawn-esque cascade of Russian paratroopers as his wife and child ran to safety.

Despite the commercial success of the AR-7, in 1961 Fairchild parted ways with ArmaLite. The Pegasus took flight from the ArmaLite logo and was replaced by a lion, although the winged horse stayed on the AR-7’s receiver casting throughout its production. Through the ’60s, AR-7 sales kept the company afloat while it designed new products such as the AR-17 “Golden Gun” shotgun and the AR-18 rifle. In 1964, ArmaLite dropped the AR-7 into a Monte Carlo-style wood stock and offered it as the “Custom” model, which added 1 lb. to the overall weight and $15 to the price.

By the 1970s, ArmaLite had decided its destiny lay with military sales. In 1973, as part of the company’s process of eliminating civilian products and focusing on the defense industry, ArmaLite sold the manufacturing rights of the AR-7 to Charter Arms. The move gave the handgun manufacturer its first rifle product. Charter President David Ecker put one of the first AR-7s the company produced through its paces for three months before announcing its sale to the public, storing the rifle on his saltwater fishing boat and using it to dispatch the occasional shark. The new Charter-produced AR-7 stayed true to the original design and retailed for $64.95. Charter Arms ads called the AR-7 the “world’s only unsinkable, come-apart rifle” declaring it ideal for everyone from RVers to snowmobilers.

In 1980, Charter Arms expanded the AR-7 line by introducing the Explorer II pistol. Unlike Hy Hunter’s Bolomauser, the Explorer II used a modified barrel and receiver to prevent the pistol barrel from being attached to the rifle, or a rifle stock being added to the pistol. The design used a modified open rear sight for a handgun-appropriate eye-relief and made provision for an extra magazine in the pistol’s Broomhandle-style grip. Barrel lengths of 6", 8" or 10" were available and finish options included gold, camouflage and a corrosion-resistant silver, in addition to the standard black. Sales of the Explorer II were dismal, and the model was discontinued in 1986.

By the time the Iron Curtain fell, and faced with newer technology and a changing world, both the AR-7 and the Air Force’s B-52 appeared headed for the dust bin of history. In 1990, Charter Arms ended production of the AR-7, selling the rights to Survival Arms, whose notable change was making the rifle’s barrel entirely out of steel. In 1998 the design was sold to AR-7 Industries, LLC which, produced the rifles into the early 2000s.

In 1998, the single event that did the most to keep the AR-7 alive occurred. Henry Repeating Arms Co., then of Brooklyn, N.Y., started producing its own version. By then the AR-7 patent had expired, so the company reverse-engineered the design. It called the resulting product the “U.S. Survival Rifle.” In the nearly two decades since, Henry has become the most prolific AR-7 manufacturer, producing more than a half-million units.

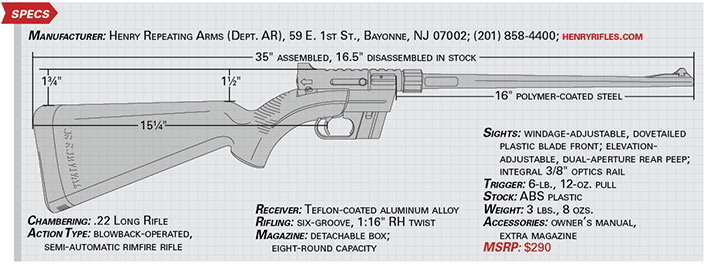

While the company touts the improvements it has made, its version stays very close to the original. The most obvious changes are external. The rifle’s stock has been given a textured, matte finish that is grooved in the grip area, a functional improvement over the slick surface of the original stock. Instead of being encased in aluminum, the steel Henry barrel is shrouded in plastic and the receiver is given a Teflon finish. The rifle is offered in matte black or a Mossy Oak Break-up camouflage finish. In 2007 an optics rail was added to the upper receiver. Though it looks like a Picatinny rail, in reality it is a 3/8" groove design for rimfire rings. Henry has redesigned the inside of the stock so that the action can be inserted with its magazine in place. This feature, in addition to space for two spare magazines, means that 24 loaded rounds can be carried, compared to previous AR-7s which had provision for only a single magazine in the stock.

The resulting rifle weighs about a half-pound more than the original ArmaLite AR-7. The weight difference is found mainly in the action, which features thicker castings than the original. Henry ships its product in a cardboard box that fits the rifle stowed inside its stock, the way AR-7s have been sold since the beginning, and it includes the company’s limited lifetime warranty.

In the field there are three questions to be asked of an AR-7; is it reliable, is it accurate and does it float? With its many manufacturers through the years, certain AR-7s have gotten a reputation for dubious quality and reliability. Henry states that reliability was its top priority when designing the U.S. Survival Rifle. To achieve top functioning, it recommends using only factory magazines and round-nose 40-gr. high-velocity ammunition. Under those conditions, I found the rifle completely reliable through 500 rounds of testing. In addition to 40-gr. fodder, I tried Remington hyper-velocity hollow point Yellow Jackets, with their truncated 33-gr. bullet, and bulk Remington Golden Bullets of the 36-gr. hollow point variety. The rifle functioned perfectly with those as well. The only way I was able to induce a failure was to go against the company’s recommendation and try other manufacturers’ magazines, which often failed to feed.

Henry also recommends cleaning the rifle every 100 rounds, solid advice for any semi-automatic .22, but I purposely neglected the rifle throughout the test. After all, it is designed for less-than-ideal circumstances. The Henry AR-7 faced hundreds of rounds and a few dunks in muddy water. In spite of the proverbial “ridden hard and put away wet” treatment, it functioned without a hitch.

The 50-yd. range at which I tested the gun is pushing the limits of the Henry’s sighting system. The front blade is easy to see through the smaller of the rifle’s two rear apertures, but at 0.08" wide, it’s not very precise. Group sizes averaged just over 2½".

The AR-7’s purpose is taking small game at relatively close ranges, and for that task its accuracy is acceptable. Out to 50 yds., it’s easy to make shots on small-game-size targets from field positions. I found the best shooting position to be a two-handed grip on the buttstock, similar to the hold for firing a handgun. There’s ample real estate in the grip area of the bulky hollow stock for such a position, which allows the elbows to be pulled into the chest to steady the ultra-lite rifle.

Does it float? Well, sort of. While the original ArmaLite AR-7 used a foamed-filled stock that made it a reliable floater, the Henry uses a hollow plastic stock. The Henry’s buttstock cap doesn’t make a waterproof seal, so the stock eventually becomes waterlogged and sinks. With the rifle stored inside, that occurs in about two minutes—or about six minutes with the rifle assembled. Either would be ample time to recover the AR-7 if it were dropped in water. (Watch the author's video, "The Unstoppable AR-7 Survival Rifle."

Nearly 60 years after ArmaLite designed it to keep its company afloat, the AR-7 is not only surviving, it is thriving under the auspices of the Henry Repeating Arms company. With the rise of “prepper” culture, a new generation of survival enthusiasts are once again discovering the unique, compact and reliable AR-7, and into the 21st century the rifle continues to find its way onto the big screen when a hi-tech, takedown spy gun is needed.

The Internet is full of anecdotes about the AR-7’s shortcomings, but most of the rifle’s perceived defects come from trying to use it for a purpose for which it was not intended, kind of like comparing your Leatherman to a full MAC toolbox or talking about how your backpacking stove is nothing like the convection oven in your kitchen. Are there other .22s out there that are more accurate, more aesthetically pleasing or more “tacticool?” Sure. Is there another rifle that fits in its own stock, assembles in half-a-minute and hits what you’re aiming at when the chips are down? No. The truth is the AR-7 is a very specialized piece of equipment and in the last 50 years no one else has come up with a design that fits its niche better. More than just a survival tool, it’s a survivor that continues to find its way into boats, backpacks and bug-out bags, and probably will for another half-century. And, by the way, those Cold War-era B-52s, yeah, they’re still flying too.

The Israeli Connection: A Mysterious AR-7 Lives Up To The Hype

It seemed like a gun myth—those too-good-to-be-true stories that circulate back and forth around Internet forums and through collecting circles until they’re taken as gospel. In the mid-1990s, strange little AR-7s featuring sliding wire stocks, foreign markings and ported flash hiders were being re-imported to the United States from Israel by Briklee Trading Company. Appearing in the pages of Shotgun News, the guns allegedly had mysterious military origins in the Middle East and were a rare piece of clandestine history. It sounded typical of the tendency among gun enthusiasts, when lacking information about an interesting firearm, to make up an extraordinary story.

Then came the headlines in 2010. Israeli authorities had negotiated a prisoner swap with Hezbollah in exchange for the personal effects of an Israel Defense Force (IDF) F-4 Phantom navigator who went down over Lebanon and had been missing since 1986. Among the items that were exchanged was the missing aviator’s weapon, which news reports identified as an ArmaLite AR-7. “We don’t know how these rifles were used, but we’re sure there’s quite a story to be told,” the original Briklee ad promised. Fifteen years after they were imported into the United States, that story began to come to light.

Through the years, the military origins of the AR-7 design inspired aftermarket accessories from extended magazines to folding stocks and barrel shrouds. Even in this world of paramilitary-modified AR-7s, the Israeli pilots’ rifle stands out. First, the rifle’s trademark hollow buttstock was replaced in an Israel Military Industries (IMI) factory with a locally produced collapsible wire stock and a pistol grip borrowed from the FN-FAL. The result was very similar to the U.S. M4 survival rifle. One only had to screw the barrel on and extend the stock to get the rifle into action, a process that takes a few seconds. Disassembled, the entire package was less than 13.5" and weighed just under 4 lbs.

The basic AR-7 action was retained without modification, along with its standard eight-round magazine. Two additional magazines were supplied and attached to the stock with a sheet metal holder. The barrel was shortened to 13.5" and equipped with a K98 Mauser hooded front sight to replace the original ArmaLite sight lost in the shortening process. An FAL-style front sling swivel was added to the barrel, to which was attached an olive drab web Uzi submachine gun sling. Most of the rifles had the ArmaLite logo and markings on the right side of the receiver removed, although other original markings, including the serial number, were left intact.

Individuals employed by Briklee at the time estimated that only a few hundred of the Israeli AR-7 rifles were imported into the United States. The company silver-soldered a 3" extension to the muzzle to bring the rifles’ barrels up to a legal length and shipped them with an original cleaning kit, consisting of an oil bottle and pull-though, and a red plastic device that fit over the receiver to block the safety and keep the bolt from being retracted. The Briklee manual warned that this AR-7 would not float.

Why did the Israelis issue a .22 to their fighter pilots? Most obviously the rifles were intended as a survival weapon, to forage for food in the event of a crash in a remote area, the task for which the AR-7 was originally designed. But it also seems the Israelis chose the AR-7 to provide their pilots with a defensive “escape and evasion” weapon. There is little spare room in the cockpit of a modern fighter jet. While the pilots of combat helicopters or other support aircraft have the space to stash a submachine gun or rifle, fighter pilots are usually restricted to a handgun. From the ’60s through the ’80s, Israeli fighter pilots were routinely issued 9 mm Luger Beretta M1951 pistols with their eight-round magazines. The AR-7 would give fliers shoulder-mounted firepower.

Compared to contemporary arms, the AR-7 was the smallest and lightest shoulder-fired, semi-automatic rifle available at the time. Israel’s own Uzi submachine gun, for example, is 18.5" in length with the stock folded, is twice as wide as the AR-7 and weighs nearly 8 lbs. Though the .22 Long Rifle cartridge seems like a strange choice for a combat arm, the IDF has a history of using .22 rimfires for offensive and defensive purposes, from Beretta Model 70 and 71 pistols to suppressed Ruger 10/22s. One advantage of a .22 Long Rifle is the ability to carry a large amount of ammunition in a small space. With 24 rounds loaded in its magazines and an extra 40 loose rounds stored in the hollow pistol grip, the Israeli AR-7 carried a payload of 64 rounds.

The Israeli AR-7s were issued to the pilots and navigators of F-4 Phantom “Kurnass” fighter jets, stowed in the survival seat packs of the aircrafts’ Martin-Baker Mk. 7 ejection seats. Ironically, Fairchild, whose ArmaLite division was responsible for the original AR-7, made components for F-4s as a subcontractor for McDonnell-Douglas.

The AR-7 gave the Israelis a solution to a problem that continues to dog military aviation—how to arm fighter pilots who may be shot down into territory where the laws of war may not apply. Last year, the Netherlands announced that it was arming its F-16 pilots flying over Syria with Brügger & Thomet MP9 submachine guns to give them a fighting chance should they have to eject over ISIS territory.

The IDF “escape and evasion” rifle is a rare and unique piece of ArmaLite and military aviation history. It seems like the rifles lived up to Briklee’s promise. Not all good stories are a myth.

AR-7 Accessories

Throughout its lifetime the AR-7 has inspired a vibrant aftermarket, starting with the companies that built the survival rifles. ArmaLite sold the Monte Carlo wood stock of its Custom model separately as an accessory for those who wanted to dress up their plastic and metal AR-7s. When it started manufacturing the rifle, Charter Arms followed suit, making a scope mount that attached through the screw hole that holds on the left receiver sideplate, giving AR-7 owners the chance to attach optics to their rifles.

Soon after it was introduced, a few companies, such as Hy Hunter, designed accessories to modify the AR-7’s appearance. In the 1980s, Mitchell Arms produced a kit that included a pistol-gripped sliding wire stock and barrel shroud, and Choate Machine and Tool made a one-piece nylon stock with a fixed butt and pistol grip. Though long discontinued, these accessories still show up from time to time on online auction sites and message boards.

Today, AR-7 Customized Accessories, LLC (ar-7.com) is the top source for aftermarket parts for the rifle. The company sells all-steel barrels in both the original profile and in heavy “target” forms with optional threaded muzzles (1/2x28) and an available cantilever scope mount that attaches to the barrel to maintain zero when the rifle is disassembled. Its adjustable tube-type stock mounts an AR-15-style pistol grip. AR-7 Custom Accessories also sells original-style parts it claims will fit all AR-7 models from the original ArmaLites to the current-production Henrys, including parts for the Explorer II pistol.

Hy Hunter was the first to attempt to increase the rifle’s capacity by taking two original eight-round magazines and welding their baseplates together to make a 16-shot “over-and-under” magazine. Ramline later made an AR-7 version of its famed 25-round plastic curved magazine. Triple K Manufacturing (triplek.com) currently makes all-metal 10- and 15-round extended magazines, in addition to original eight-round capacity models. To address the AR-7’s lack of sling mounts, Slim River (slimriver.ecrater.com) offers a sling system that attaches to the buttstock and allows for the use of single or two-point slings and has an optional magazine carrier. The slings allow the rifle to be carried assembled, or stowed using the stock like a holster.

Besides spare parts and magazines (including a five-round model for areas where that is the maximum capacity allowed by law) Henry offers a survival kit that includes everything from first aid and fire starting material to a compact flashlight and multi-tool, all stored in a pocket-size waterproof aluminum container.

The AR-7’s self-reliant vibe gives it a certain “DIY” appeal. A quick Google search of “AR-7 custom” turns up many handcrafted “hacks” from paracord slings to folding stocks. Whether purchased or homemade, adaptability remains the AR-7’s virtue. Like another well-known rifle whose name begins with “AR,” the ability for an individual to tailor an AR-7 to his or her specific needs has led to its longevity.