The U.S. Model 1918A2 BAR served G.I.s well in World War II and Korea and was a modified version of Browning’s original design. Accoutrements courtesy Chris J. Anderson and Ivan F. Ingraham. M1918A2 courtesy National Firearms Museum.

This article was first published in American Rifleman, August 1997

Without question, America’s most prolific and revered arms designer was John Moses Browning. The Utah native’s contributions to the field of small arms development are unparalleled. The guns he invented for the commercial and sporting market are almost too numerous to list and many of his designs are still made today. While sometimes overlooked, Browning-designed military arms are even more impressive. One of the most important U.S. military arms of the 20th century will forever, fittingly, bear the name of its designer, the Browning Automatic Rifle.

Generally referred to by its initials, the BAR set the standard for automatic rifles from its inception during the First World War and for several decades afterward. Few U.S. military arms elicit as much widespread admiration as does the venerable BAR. Many veterans of the Second World War and Korea remember the BAR as a reliable and very effective arm. While many gripes were lodged against the gun’s weight, few complaints were heard when the chips were down in actual combat. The BAR proved its worth on countless battlefields around the globe for over three decades.

The BAR had its roots in the trenches of France during World War I when both sides were mired in bloody and protracted trench warfare. When the U.S. entered the war on April 6, 1917, it soon became painfully obvious that our armed forces were woefully unprepared to fight a modern war. With the exceptions of such excellent arms as the Springfield M1903 rifle and the Colt M1911 .45 pistol (both, incidentally, in short supply), our troops were primarily equipped with obsolete and generally unsatisfactory arms.

One of the most serious gaps in our armament capability was the lack of a satisfactory light machine gun. An automatic that could be used by troops moving to the assault was desperately needed. Our French allies had attempted to fill this void with the Fusil Mitrailleur Modele 1915 ‘CRSG’ (Model 1915). Chambered for 8 mm Lebel, it was generally referred to as the “Chauchat.” Our doughboys soon fractured the French pronunciation and called it the “Sho-Sho.” The U.S. purchased some 16,000 Chauchats from the French, and our troops quickly discovered that it was extremely unreliable, and found it ineffective and unpopular. Clearly, a better arm of this type was needed by our troops.

Fortunately, the legendary John M. Browning had quietly been working on a design of his own for a reliable and effective automatic rifle. Browning had previously entered into a working agreement with Colt Patent Firearms Co. which had obtained the rights to the design from the inventor. On May 1, 1917, the Secretary of War convened an ordnance panel to test and recommend for adoption a light machine gun or automatic rifle. Browning’s was quickly adopted. It was known as the “Browning Automatic Rifle” and was soon referred to primarily by its initials “B-A-R.” The BAR was chambered for the standard M1906 (.30-’06) cartridge and was capable of semi-automatic or fully automatic operation at the rate of some 550 rounds per minute.

Since the Colt plant at Hartford, Connecticut, was already operating at peak capacity, the firm wished to establish another manufacturing site in Meridian, Connecticut, to produce the BAR. The Ordnance Department did not agree as a maximum number of BARs had to be produced in the minimum period of time; and a new factory would have required training an entirely new work force. The logical solution was to seek other sources, and, to this end, the government reached an agreement with Colt and John Browning to acquire the patent rights to the gun “for the duration” of the war.

In September 1917, the Marlin-Rockwell Corp. and Winchester Repeating Arms Co. were awarded BAR production contracts. Colt also received a BAR contract within the rather strained capabilities of its Hartford plant. All three firms were already heavily involved in arms production, but the new automatic rifle was deemed a priority and the firms began to tool up rapidly. There were no engineering drawings or even detailed specifications for the gun since the only working model in existence was Browning’s handmade prototype. Winchester’s engineering department was allowed to borrow the prototype from Colt for just one weekend. Working literally around the clock, they made the necessary production drawings and blueprints from the prototype and returned it to Colt the following Monday morning. Winchester then assisted the Marlin-Rockwell Corp. in setting up its own production line.

Winchester began delivery in December 1917, Marlin-Rockwell in January 1918 and Colt in February 1918. Although the BAR was actually adopted in 1917, it was designated the “Model of 1918.” This was presumably done to prevent confusion with the Browning Model of 1917 water-cooled machine gun. BARs began to flow from the production lines, and limited issue to our troops overseas began by the late summer 1918. Interestingly, it was first demonstrated in France by Lt. Val Browning, the inventor’s son. After familiarization and training, the BAR began to be issued to front line troops and used in actual combat.

The first recorded U.S. Army use of the BAR in combat was on September 12, 1918, in the hands of the 79th Infantry Division. The BAR immediately proved to be an unqualified success as a combat arm. Compared to the wretched Chauchat, it was a godsend. As stated by the Assistant Secretary of War in 1919:

“The [BARs] were highly praised by our officers and men who had to use them. Although these guns received hard usage, being on the front for days at a time in the rain and when the gunners had little opportunity to clean them, they invariably functioned well.”

Our troops were still in the process of fielding the BAR in quantity when the war ended in November 1918. At the time of the Armistice, some 52,238 Browning Automatic Rifles had been delivered. It remained in production until the latter part of 1919 by which time 102,125 M1918 BARs had been manufactured.

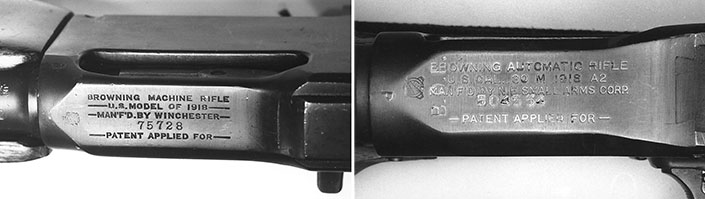

The M1918 BAR was gas-operated and weighed some 16 lbs. While this might seem heavy, it was actually a lightweight compared to contemporary automatics of the day. The BAR had a 24" barrel with a screw-on cylindrical flash hider. The top of the barrel was marked with the initials of the manufacturer and the month and year of production. The model designation, manufacturer and serial number were stamped on top of the receiver. All metal was finished in an attractive commercial grade bluing and the stock and checkered forearm were made of walnut. The BAR was robust and its entire receiver machined from a solid block of steel. The non-reciprocating charging (cocking) handle was on the receiver’s left side. The rear sight and buttplate were the same type as used on the U.S. M1917 “Enfield” rifle. Unlike later versions, the original Model of 1918 was not fitted with a bipod. The BAR was equipped with a 20-round detachable box magazine. It has been reported that larger capacity versions were tested, but none have been observed.

The BAR was also issued with a special cartridge belt with a metal “cup” on the right side into which the butt was inserted. This enabled it to be used in the “marching fire” mode of operation that was envisioned for the BAR. The belt also had four pockets that held two magazines each and a pouch for two M1911 .45 pistol magazines. Grommets on the belt allowed for a pistol holster, canteen, first aid pouch and similar items to be carried on the belt. An “Assistant Gunners” belt was also produced that had four magazine pockets and several more pockets for rifle stripper clips. The BAR was issued with a leather sling similar to, but longer than, the M1907 rifle sling and with three metal adjustment hooks.

After World War I, the BAR stayed on in Uncle Sam’s inventory and saw a surprising amount of service in various small-scale military actions around the globe in the 1920s and 1930s including China, Haiti and Nicaragua. Colt produced a commercial version of the Browning Automatic Rifle known as the “Monitor,” but sales were limited due to the ready availability of standard military BARs. Some BARs were stolen from National Guard armories and other sources and used by some criminals during the turbulent times of the ’20s and ’30s. The BAR played a prominent role in the downfall of two of the most notorious criminals of the era, Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, and one was in the hands of the law enforcement officers who fatally ambushed the infamous duo.

In 1922, a smaller and lighter experimental BAR was tested by the army for cavalry use but not put into production. In 1937, the first major variant was adopted as the “M1918A1.” It was identical to the M1918 but had a hinged bipod with spiked feet attached to the gas cylinder. It was also fitted with a folding buttplate to help keep the gun on the shoulder when firing full-automatic. The handguard was cut down in height to expose more of the barrel for better cooling. M1918A1s were modified from existing M1918 BARs, so there was no separate production.

Just before America’s entry into World War II, the final and most widely produced version of the BAR was adopted as the “Model of 1918A2.” The M1918A2, like the M1918A1, was fitted with a hinged bipod, but the latter’s was attached to a special flash hider on the barrel rather than on the gas cylinder. A modified buttstock with a folding buttplate and provision for a monopod was also adopted, although the monopod saw very little use. The fore-end was reduced in height and length and the rear sight was replaced by one similar to the type used on the M1919A4 air-cooled machine gun. Metal guide ribs were added to the front of the trigger guard to assist in changing magazines. Unlike the M1918 and M1918A1, the M1918A2 was not capable of semi-automatic operation. It fired only in full-automatic and had a slow and fast rate of fire; approximately 300-450 r.p.m. and 500-650 r.p.m. respectively. The modifications and additions added substantially to the BAR’s weight and the M1918A2 weighed some 20 lbs. as compared to M1918’s 16 lbs.

Initially, M1918A2s were produced by converting M1918s, and thousands were converted to M1918A2 specifications primarily by Springfield Armory during the early 1940s. A number of unaltered M1918s were sent to Great Britain under Lend-Lease (often seen with red bands painted on them) and escaped conversion. Also, some M1918s were never converted to the ’A2 specs and were issued and used during World War II.

After Pearl Harbor, BAR demand increased dramatically and new production sources had to be found quickly. The government contracted with two commercial firms; International Business Machines (IBM) and New England Small Arms for M1918A2 production. These two firms delivered a total of 208,380 BARs to the government during the war. This was in addition to the earlier BARs.

The BARs were soon in the thick of fighting and they once again proved to be effective and reliable. An illustrative example of the BAR’s performance is contained in a 1943 Marine Corps report:

“Browning Automatic Rifle, cal. .30, M1918A2. The weapon continues in popularity. It functions under all conditions with few exceptions and stoppages, and has the striking penetrating power desired in the jungle.” Despite the BAR’s weight, it provided excellent service to our troops during World War II and was widely praised. The biggest advantage of the BAR over .45 cal. submachine guns was the penetrating power of the .30 cal. cartridge. The BAR’s rate of fire and reliability were much appreciated by our combat troops."

The most common complaint lodged against the M1918A2 was its weight, which exceeded 20 lbs. To help reduce the weight some removed the bipod. Lt. Col. John George commented on this situation in his book Shots Fired in Anger:

“Two weeks after we were on Guadalcanal we had thrown away all the gadgets (bipod, etc.) and were using the guns stark naked ... the way old John Browning had built them in the first place.”

The BAR’s role had shifted somewhat from providing “marching fire” to troops in trench warfare to becoming the standard squad automatic weapon. Many unit commanders sought to obtain as many BARs as possible for their troops. The only other automatic rifle fielded by the United States during the war was the M1941 Johnson Light Machine Gun. The Johnson had some innovative design features and was much lighter in weight than the BAR. However, it was only modestly used during the war.

The BAR was the U.S. squad automatic weapon of the war. Although it was a superb performer in many applications, it had a number of deficiencies as well. Its weight prevented it from being used as a true automatic rifle, and it essentially played the role of light machine gun. However, due to its design, it was not capable of sustained automatic fire as were the Browning M1917A1 and M1919A4 .30 cal. belt-fed machine guns. The BAR’s limited magazine capacity was one detriment, but the fact that the barrel could not be easily removed and replaced was a serious drawback. Sustained automatic fire could rapidly burn out a barrel. The BAR’s barrel could only be removed and replaced by an ordnance depot. Some experimentation with adapting the BAR to belt feed and a more readily replaceable barrel was done, but required extensive modification of the receiver and was not practical. Due to these factors, it was actually somewhat of an anachronistic arm by end of the Second World War.

After World War II, the BAR was extensively used in Korea where it provided excellent service within its limits. It was again placed back into production during the early 1950s when several thousand were manufactured by the Royal McBee Company. These Korean War-vintage M1918A2s were very similar to late production World War II BARs and were fitted with a carrying handle attached to the barrel. This made carrying it for short distances a bit easier but further increased its weight. The “all purpose” M60 machine gun was adopted in the late 1950s as a replacement for several arms including the BAR. However, a number of BARs remained in inventory well into the Vietnam War era, and many were supplied to the South Vietnamese and other allies.

The BAR’s days as a front line automatic rifle are over. However, few U.S. military small arms have garnered a better reputation or are looked upon with more respect than John Browning’s automatic rifle. From its baptism of fire in the trenches of France in 1918 to the steaming jungles of Guadalcanal or the frozen Chosin Reservoir, the BAR has served this nation with distinction.

![Winchester Comm[94]](/media/1mleusmd/winchester-comm-94.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=770&height=430&rnd=134090756537800000&quality=60)

![Winchester Comm[94]](/media/1mleusmd/winchester-comm-94.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=150&height=150&rnd=134090756537800000&quality=60)