Such was the case last November when a runaway nine-point whitetail caused a dispute that was reported by a Wisconsin television station. After shooting the deer, an 11-year-old hunter and his dad were blood-trailing it when they heard shots from the neighboring property. There they found the landowner with the dead buck.

Legally it was the neighbor’s kill, but nonetheless a debate ensued, colored by the fact that it was the youngster’s first deer. It came down to a coin flip, which was won by the landowner, a conclusion that rankled the dad, who said, “I wish [the neighbor] would have done the right thing to begin with. All my son wants is his deer.”

The story went viral, and comments streamed in by the hundreds. Some took the youngster to task for not shooting straight, while others chastised the landowner for not giving the kid a break. And yet another, more sympathetic, group acknowledged having similar experiences, some posters asking, “What hunter hasn’t had a deer run off?”

The outcome was hardly unique. “The number one request we receive is for a load that will drop a deer in its tracks,” says Winchester Ammunition’s Greg Kosteck. “That’s what hunters ask for, and so we’ve worked hard to come up with a solution. And this time we believe we’ve got it.”

The solution is Winchester Deer Season XP, the company’s key product introduction for 2015, one that’s been in the works for several years and whose name clearly announces its purpose. Not coincidentally, the deer-hunter customer base is also targeted by the new Winchester XPR, one of an emerging class of hunting rifles that American Rifleman Editor-in-Chief Mark Keefe recently dubbed, “… the affordable, modern bolt-action.” With common elements such as push feeding, molded synthetic stocks, blued metalwork, and limited action lengths, barrel lengths and caliber options, these basic rifles may lack the workmanship that once made a big difference to riflemen, but are nonetheless proving themselves pretty darned capable.

The co-branding of the two Winchester introductions is also no accident, despite the fact that Winchester guns and Winchester ammunition are made and marketed by two completely separate companies. Along with other firearm and ammunition makers, Winchester Ammunition (Olin Corp.) and U.S. Repeating Arms (FNH USA-Browning) saw opportunity in the marketing tea leaves. Data issued by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that nearly 80 percent of the 17 to 20 million Americans who hunt are, first and foremost, deer hunters, and then in the wake of the 2008-2009 economic slump, there was an uptick in hunting license sales. Apparently renewed interest in venison was creating a demand for new guns, but those guns would have to meet certain specialized criteria. In addition to delivering practical utility at 1970s-era pricing, the designs had to be compatible with the so-called “lean” manufacturing processes that have revolutionized many heavy industries.

Ammunition lends itself to even greater specialization—take, for example, frangible varmint loadings, solids for dangerous game and short-action magnums that fit lightweight rifles, all of them tools for specific jobs. And so with the robust deer hunter segment showing signs of growth, Winchester Ammunition decided the time was right for the knockdown load its customers wanted.

Hunter dissatisfaction with terminal performance has actually been a force for change in the ammunition industry, motivating product developers to devise various successful methods for improving performance. Most noteworthy are do-everything, controlled-expansion, big-game bullets that rely on attributes such as stoutly constructed jackets, internal partitions, jacket-to-core bonding or copper/monometal composition, all of which help ensure these premium bullets hold together on impact and mushroom incrementally and consistently over a wide range of impact velocities on game ranging from pronghorns to grizzlies.

Focusing solely on deer, Winchester’s goal was different. Penetration remained important, but the degree needed to punch through the heart/lung vitals of deer meant that the bullet’s nose could expand more violently. However that expansion couldn’t occur immediately, as was too often the case with earlier bullets (especially when driven at magnum velocities) that fragmented on the hide and failed to reach vital anatomy. In a sense, Winchester sought to reverse engineer the controlled-expansion model, sacrificing nose integrity and weight retention to lethal disintegration even as an intact shank plowed into and through vital organs.

Partly because long-range accuracy and flat trajectory are important to today’s hunters, Winchester felt that a tipped bullet with a high ballistic coefficient (BC) had to be its starting point. Cost containment was also a prerequisite, since the company knew the product would sell only if priced competitively with existing popular deer loads.

The end result is the Extreme Point (XP), and it’s easy to see the tip is considerably bigger than customary plastic points. As intended, the BCs compare favorably with the highest available. Using the .277-cal. 130-gr. as an example: the XP’s BC is 0.45, the Nosler Ballistic Tip is 0.433, and Federal Trophy Copper is 0.459. Accordingly, the XP should be among the flattest-shooting hunting bullets.

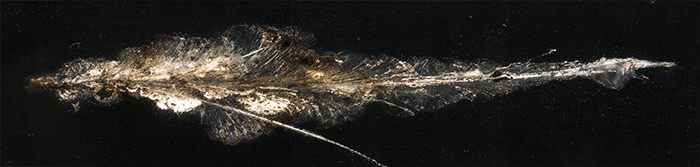

XP jackets taper from very thin at the nose to a somewhat stouter base contour, and unlike many other tipped bullets, the XP’s base is flat rather than boat-tailed. The flat base combines with the progressive jacket taper to check initial expansion and ensure a substantial core remains to drive through inner tissue.

We first learned about the project in December 2013 during a north Texas whitetail hunt with Winchester’s Greg Kosteck, who supplied pre-production cartridges topped with bullets bearing an unusually large tip.

The loads grouped nicely in our rifles, and our threesome proceeded to take three mature bucks, a hog and a coyote. Impressively, all were dropped right where they stood. Upon closer examination, it was evident that tissue damage was just as extreme as intended. Even so, we recovered just one bullet, the rest completely passing through. My buck, a broken-racked 5x4, was hit behind the shoulder at 130 yds., and the .308 Win. 150-gr. XP’s exit through the off-side rib cage tore a 3" hole, penetration on par with any well-made bullet.

In fact, extreme tissue destruction and excellent penetration have been in evidence in all of the 20 or so deer and hogs I have either examined firsthand or discussed with fellow hunters using this ammunition. Winchester has received scores of similar reports from its field testers. Not every animal was dropped in its tracks, but I know of only one instance where the hunter lost sight of his quarry after the shot.

That hunter was me, as Kosteck and I reunited last season in Oklahoma for a second field-test hunt. Also present was NRA’s Chris Sprangers, who quickly dropped a great old-timer buck that had come to feed in a wheat field. Kosteck scored too, killing a dandy 10-point. In both cases Deer Season XP met the drop-’em-right-there objective.

I knew beforehand that not every deer shot with the new ammo would tip right over, and folks from Winchester certainly know that, too. First, the hunter has to make a killing shot, and for XP to realize its true potential, those shots should be through the heart/lung area where the bullet can exert maximum effect. Even then, there will be exceptions, and in my case it produced a blood trail that made it very easy to recover the deer.

XPR–A Successor To The Model 70

With web pricing currently running in the $450 to $500 range, the Winchester XPR isn’t the category’s least expensive, but it is the only one that comes with brand equity going back to the Model 1894 lever-action, an affordable deer rifle in its own right. The succeeding Model 70, likewise was a favorite with deer hunters even if most iterations weren’t exactly inexpensive. However, in the early 2000s, Winchester actually did anticipate the coming trend via a pair of cut-rate Model 70s, the Black Shadow (push-feed) and Super Shadow (hybrid controlled-round/push-feed). Priced at around $500, they certainly raised eyebrows—and in fact the Super Shadow won a Rifle of the Year Golden Bullseye from NRA’s American Hunter magazine—but didn’t stick long in the Winchester catalog. Likely the Model 70’s production costs, high regardless of the action types, were to blame.

To compete in the hot market segment, Winchester had to come up with a new design and a new manufacturing scheme resulting in a lower unit cost. It did so, even while incorporating premium performance features.

Like a lot of current bolt-actions at low- and mid-level price points—but unlike the Model 70—the XPR is built on a round-bodied receiver joined to the barrel by a lock nut. This design, originated by Savage in the 1950s, requires fewer machining or hand-fitting steps to regulate the critical headspace dimension, and, thus, is favored by cost-conscious manufacturers. Cylindrical receivers are plenty strong, but because of their shape and limited surface, provision must be made to reinforce how they are mated to the stock. To check flexing or slippage, it’s common practice for the barrel nut washer to double as a recoil lug. In the XPR, a steel plate embedded in the injection-molded stock engages a lateral slot in the front of the receiver. The design bears some similarity to the system used on some Sako and Tikka rifles, however the XPR lug provides less bearing surface, and so it’s questionable if chamberings can ever exceed the .338 Win. Mag.

Another trendy touch is the action’s stout bolt, whose 0.877"-diameter body is larger than the 0.853" lug diameter, just the opposite of perennial favorites whose slender bolt stems end in prominent protruding lugs. The new thinking is that these smooth-riding fat bolts, especially when equipped with a short-lift, three-lug lockup like the XPR’s, make it that much quicker and easier to stroke the action.

Winchester states the XPR barrels are the same as those found on today’s Model 70s, forged from chromoly steel, button-rifled and “thermally stress-relieved to ensure accuracy.” Also premium is the firm’s MOA Trigger, introduced a few years ago to make the Model 70 more competitive. It is touted as having, “zero take-up, zero creep and zero overtravel,” and while that may be overstating things, it is solid, fast and controllable. Our test rifle’s trigger broke at a consistent 4 lbs., which is ideal for a hunting rifle mostly fired from a rest, a perfect example of why clean breaks are more beneficial than super-light pulls in exciting encounters with game. I think these two high-value components are key to the rifle’s accuracy, but it also deserves high marks for the solid two-position safety and the adjacent bolt-release tab that allows the shooter to work the action with the gun on safe.

The molded black polymer stock on our test model is styled with sculpting that “outlines” a comb and beveled edges along the barrel channel. The stock also bears impressed stippling in long fore-end strips, left and right, plus four small panels bracketing the pistol grip, as well as a cushy InFlex buttpad. I have seen Internet chat appreciative of the XPR’s looks, and I understand that sentiment, but agree only that its lines are pleasing for molded polymer.

The trigger guard/bottom unit and magazine are polymer as well, save for one metal part, the follower spring. The guard is generously shaped for big fingers, and the three-round-capacity, single-stack, detachable magazine locks snugly but does bump out about 1/4" below the stock for a look that might have been criticized at one time, but which presumably won’t be a turn-off to shooters now accustomed to high-capacity magazines.

XPRs were made available for the Oklahoma hunt where they paired with the corresponding Deer Season XP ammo. Kosteck, Sprangers and I all used the co-branded rifle and ammo to rack up one-shot kills on three deer and a hog. Further bench work produced 100-yd. groups averaging under 1.5", the best coming from the companion Deer Season XP at 1.23", indicating the shared development has legs.

It’s tough to predict if the recent wave of affordable bolt guns will become the new normal for deer hunters. As Winchester’s entry, the XPR has a tough act to follow—eight decades of Model 70s—but it certainly appears to have all the necessary features.