This article was originally published in American Rifleman, April 1942.

By Garrett Underhill, Jr.

As the lights have dimmed, and gone out all over the world, in their fading they have al-lowed the shadow of defeat to creep across many new battlegrounds of British arms. In the past two-and-a-half years, British weapons have been in action on almost every front. Royal Marines fought in the Netherlands; entire BEF's were engaged in Norway, in Flanders, in France and in the Balkans. Garrisons have been lost in Hong Kong and Crete; mixed Imperial forces battled in Burma and Malaya, while Britishers and Australians have been among the unsuccessful defenders of the Dutch East Indies and the Solomon Islands.

Where the light of victory has shone, there, too, British arms have been on the firing line. In Libya, in Syria, in Eretrea and Ethiopia they have waged successful campaigns. Heavy British infantry tanks have backed up the Russians during the past winter, and MacArthur's Filipinos use a rifle converted from the 1914 British Enfield.

Unfortunately, a great number of Americans who have come into contact with British arms have failed to understand them. They do not recognize that, as long as each nation is different culturally, the arms which are but an expression of a national culture are bound to be different. Hence, the detail or even the general build of, say, a British 3.7-inch anti-aircraft gun may be as queer to the average American as the British habit of time out for tea under any and all conditions. And to an American used to the target-range perfection of a Springfield, the complex but speedy and practical action of the Lee-Enfield will seem equally absurd.

To a certain extent, this American attitude is purely hypocritical. Both Britain and America are great peace-loving democracies. Since Prince Albert opened the Crystal Palace in 1851, we have all been firmly convinced that each war is to be the last. The consequence is that in peacetime both our armies are scorned and denied funds. Ordnance men are compelled to achieve miracles on a pittance, and to guess with the rest of the Army on what new designs can be standardized. In the meantime, work goes forward under a heavy burden of red tape, carefully imposed by the watchdogs of a people determined that not a cent shall be wasted by those enemies of world society—the "militarists".

With such a handicap, it is only natural that trouble should result. Lack of funds is a positive bar to production orders. Again and again the American Army has warned that mass production can only be achieved by mass production; that if work proceeds with small lots and orders, production must remain on a craftsmanship basis. In short, the peoples' picayune attitude towards Congressional and Parliamentary appropriations for armies must force the same thought pattern on military personnel. The armies' fight to throw off this incubus can only be successful when the clouds of war so threaten as to make peoples less careful of their pocket-books. In England's case, the difficulties have been somewhat exaggerated, because, till recently, the social caste system precluded officers' taking great interest in the technical, operational and manufacturing details of all materiel. To do so smacked of being "in trade".

The industrial differential is still more marked in view of the fact that British industry itself has operated more on a craftsmanship basis than the American. Design tends to be a trial and error process—called "practical" by our cousins. Prolonged practical experience in colonial wars —including fighting on the Northwest Indian Frontier right up through the present—has given the British Army a penchant for this school of thought. They feel that they can boast of superior field experience, and so not infrequently they criticize the amount of Teutonic forethought which goes into our weapons. They maintain that ours have a layout too obviously "planned from the start," and that theirs, however "muddled through," are more practical.

If the American can bear in mind these facts, and look for the mote in his own eye the meanwhile, he is prepared to appreciate British weapons—even if he does find them heavy-looking, as solid as a good British beefsteak—and often too intricate for really fast production.

Undoubtedly the basic British rifle furnishes the best example of a typical British arm. This rifle is the Short Magazine Lee-Enfield of 1903. Unlike our Springfield, which was tested first in 1901 and appeared in 1903, it has a long history of gradual development. It is a direct descendant of the Lee-Metford of 1888—the first small¬bore, high-velocity magazine rifle adopted by the British. By a series of changes, carefully designated by different names, Marks and Stars (*), the Lee-Metford has muddled into the Lee-Enfield of today. Like the Springfield, the "short" Lee-Enfields are compromises between infantry rifles and cavalry carbines. As universal arms they are therefore shorter than the old rifles, and have a normal length of 3 -feet 8 ½ -inches. At present, those in wide use consist of two variations. Both are manually-operated Lee bolt-action 8-pound, 10-ounce pieces, rifled on the Enfield system, and fitted with 10-shot protruding Lee magazines fed by .303 rimmed cartridges in "chargers" (clips) of five. The older type, adopted in 1907, is the SMLE Mark III, which has a cut-off sliding from the right side in between the bolt and magazine. Another distinguishing feature—but only of the earlier Mark III's—is the long-range sight on the left side, consisting of a rear peep and adjustable front button sight graduated from 1700 to 2800 yards. These sights, useful mainly for group firing on areas where enemy personnel has been located, were dropped after 1916. The newer version, approved in 1918, discarded both the cut-off and the long-range sight. Called the Mark III* this rifle was furnished with a flat cocking piece, so constructed as to be interchangeable with that of the Mark III. Many mongrels will be found with the parts of both Marks mixed up.

After being fed with various and sundry cartridges since 1888, the British service rifle now fires Mark VII ammunition, giving a muzzle velocity of 2440 foot-seconds. Though cordite is a notorious barrel-fouler, 37 ½ grains of it propel each 174-grained jacketed bullet in Mark VII rounds. The cartridge permits a ramp sight zeroed at 200 yards, with a maximum setting of 2000 yards attainable in 25-yard increments, or by micrometer setting at 5-yard intervals through use of the worm-wheel on the right side of the sight leaf.

While it is true that the Lee-Enfield is a bulky and gadgety-Iooking weapon even to an American accustomed to the deluxe devices of our 1903 Springfield edition of the Mauser, the Lee-Enfield is still a very serviceable arm. In the course of its development, its various models and ancestors fought scores of colonial engagements. Renowned for sturdiness, its action has stood up during many a fire-fight from the sub-zero temperatures of the Arctic to the searing heat of the sandy and dusty deserts of Africa and Asia.

Perhaps because old-style British officers could be great rifle shots without losing caste, no mean attention was given to the consideration of fast, accurate fire under field conditions. Towards this end, the butt has been made removable, so that long, normal, short and even bantam butts may be issued to make the rifle fit the man. Americans may scorn the lack of sling-use and howl at the cocking-on-locking bolt action, but the combination of action design and 10-round magazine is excellent for accurate rapid fire. Dubs can soon attain 10 aimed shots in 40 seconds. Experts have gotten off a phenomenal 60 rounds in a minute.

While well muddled through, and a practical field weapon for the rifleman, the Lee-Enfield is not eminently designed for production. The gauging during manufacture is such that interchangeability of parts is unsatisfactory by American standards. The receiver is a hard machining job, and with all the complexity of fitted butts, fancy muzzle caps and odds and ends, in the four years of the last war there were never enough Lee-Enfields of the Mark III and III* variety. They had to be supplemented by older rifles, and in the Royal Navy they were actually replaced to no small extent by Japanese Arisaka rifles and carbines. The different rifles, the different Marks, stars and types of small arms ammunition all militated against good industrial and maintenance doctrine.

As is bound to happen in democracies where unpreparedness overrules armies, that the Lee-Enfield is here at all today is somewhat of a misfortune. Before the outset of the last war, the British Army had hoped to go over to a new rifle using a ballistically excellent semi-rimless .276 cartridge. The new rifle was to be a Mauser—though the bolt locked on cocking—and was called the Enfield Pattern 13 (1913). Several hundred were manufactured at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock on the Thames. These were issued to troops for service test. When the war came, it was too late to make the change, and so the new rifle was converted to .303, called the Pattern 14 (1914). It was sent to Remington and Winchester for mass production. Far easier to make than the SMLE's, it was rushed out to arm the home Volunteers, and troops abroad. So far as is known, it saw service only in the Near East.

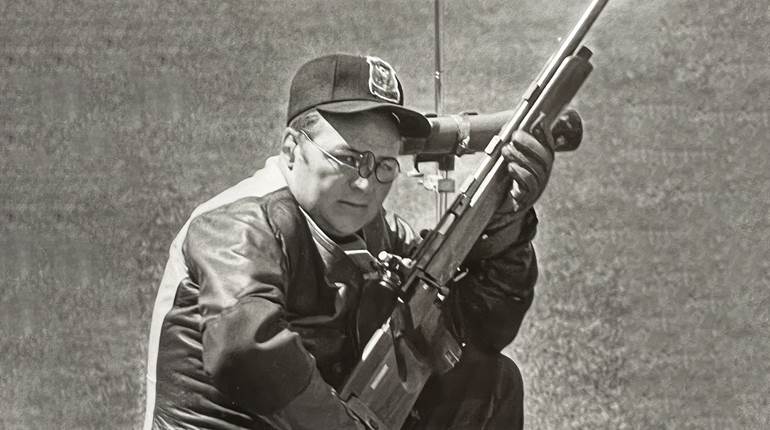

This Pattern 14 is, of course, the rifle that was smoothed up and chambered to take the .30-'06 as our Model 1917 when America joined the fight against the Kaiser. As such, it is the rifle which armed the majority of our Army when the Springfield couldn't be produced fast enough. Most Americans know it. Some—especially trench fighters—think it long and unwieldy. In reality it is only 3-feet 10 ½ inches (31/4-inches longer than the Springfield, 2-inches longer than the SMLE), though it does weigh 10 pounds. Nevertheless, it is undoubtedly an accurate and very practical weapon. The target experience of the British volunteers proved its accuracy to such a degree that after 1918 the War Office selected it as a sniper's weapon. Fitted with a telescope of the Aldis pattern, it has been issued to snipers and is in that use today.

Lack of preparedness has brought the Pattern 14 out again in this war—because once more the Lee-Enfield cannot be produced in quantity, though England, Canada and Australia all strive together. Photos show that even crack British regiments have been furnished this long rifle. When lend-lease began, America was called on to supplement the deficiency of British small arms, and so in the Canadian Royal Air Force and in the Home Guard in England can be seen the American model 1917 Enfields, carefully distinguished from their .303 brethren by a red band brilliantly painted around the forestock. Thus Enfields are now in use in our State Guard, in the Philippines, and in Canada. In England they are but another rare species among the Home Guards' Ross rifles, Lee-Metfords, Swiss Vetterlis, and other veterans too diverse to mention.

Unfortunately this war also caught the British with a new rifle in the test stage. This rifle succeeded a modification of the SMLE Mark III* which was called the Mark V (Mark IV's are conversions from Marks previous to the III). After tentatively approving the Mark V in 1922, and making a few in 1925, this Mark was superseded in 1929 by the new Mark VI now in issue. By and large this new rifle resembles the earlier Marks, but the rear sight is now a peep, and has been moved back over the receiver in order to be close to the eye as in the Pattern 14. The whole receiver has been squared and cleaned up to change the design from that of a peacetime hand-made job to a type more suited to wartime mass-manufacture. The barrel is heavier and stiffer. The method of stocking is simplified, and the safety and action likewise smoothed for production as well as improved slightly. The luxury hunters and perfectionists have also lost out in the muzzle, for now the complex muzzle cap is dropped. The sight with its dog-ear guards has been brutally roughed out and moved down so that the bayonet fixes directly to the barrel. As for the bayonet itself, it has been sensibly shortened from 15 to 7 inches. Now it can ride right on the muzzle without tieing the barrel to the forestock, while retaining enough length for thrusting effectiveness. More than 6 inches of bayonet in man is likely to bind and cause a broken blade when the stickee twists and falls in his death agony.

Under all these circumstances, it cannot be said that a completely new model has been introduced, even though the Mark VI replaces all Marks now in service in the next few years. Basically the SMLE remains the same, but in this new version indicates a growing British appreciation of manufacturable design. Certainly it shows how difficult it is for an Army to make progress in a Democracy. After almost thirty years of attempted change, spoiled by parsimony and war, the British are still relatively where they were in 1907.

Those who deny that the British are held back on semi-automatics by their mossbacks can with reason point to the rapid adoption of the tommy gun, once its worth in war had been demonstrated to British troops in the face of the enemy. When the Norwegian BEF found themselves chasing up crag and down mountain, trying to make a 22-pound Bren as handy, portable and unfatiguing an automatic weapon as a 9-pound German Schmeisser—and when their officers and NCO's had tried to make their service revolvers (almost worthless over 20 yards) compete with a tommy gun that even a nervous man can spray death with at 200 yards the British ordered the Thompson submachine gun in quantity from America. At first the drum magazines containing 50 caliber .45 cartridges was supplied. Now late types produced by the Auto-Ordnance Corporation are fed from a vertical 20-round box magazine of the type the Finns found so effective in their Suomi. This tommy, or "squirt" gun is fitted with a muzzle-brake to keep the barrel from climbing and firing at the rate of 400 to 800 rounds a minute, is ideal for the soldier who recognizes that, at close quarters, he will be too frightened to use non-machine weapons effectively.

Down in the Western Desert—the Libyan Desert—quantities of German 11.5-mm. Schmeissers may be seen in use along with the Thompsons. As a supplement to their mass-produced Thompsons, the British are supposed to have a new squirt gun of their own. Australia, too, has recently stated that she is manufacturing a tommy gun designed by a young Lieutenant, Evelyn Owen. One advantage claimed is lightness, though its 10 ½ -pounds totals a little more than the weight of the average Thompson. Australians state that it has greater velocity and penetration, but how this can be achieved without a new cartridge is not clear. Why there is need for much penetration in a man-stopper likewise is obscure. The distinguishing characteristics are easily visible from photos, and one can well understand therefrom why it is reputedly very simple to manufacture. One thing about it is certain; the Owens is an all-Australia gun. It is hoped that politics and, insularism are not involved, for if they are, and Australia survives, this gun may cause friction between Empire forces.

The British Bren light machine gun is derived from Czech designers who worked for the Czech Army. As the original gas-operated Praga or Z.B.-26 (1926) manufactured at the famous Czech factory at Brno, it has been sold to and used by Czechoslovakia, China, Lithuania, Loyalist Spain, Yugoslavia, Rumania and by Russian guerillas. The Japs have kept them for use whenever they have captured them from the Chinese, who now make them them¬selves.

When the Bren was finally selected, it was because the British wanted sustained fire. To obtain it in an air-cooled light gun, barrels must be quickly changed. With a Bren, after firing 10 magazines at the rapid rate, the operator merely raises the barrel locking nut catch found on the left. This turns the nut, frees the barrel lugs and permits the hot barrel to be drawn forward and out by the carrying handle attached to it. The whole process of removing a 6-pound barrel takes 6 to 8 seconds.

Unsatisfied with the gun as it was, the British made the barrel heavier for accuracy-—for this would prevent jumping around, and also assist in avoiding excessive heating. All the light flanges were removed, as the British did not believe them essential to cooling. Magazine capacity was upped from 20 to 30 rounds, and magazines made loadable from rifle clips by hand in 40 seconds. The fire-rate was cut from 600 rpm to a more sedate 450. The actual rate delivered with accuracy was determined to be 120 per minute, and the normal rate set at 5 bursts of 4 or 5 rounds—or one magazine per minute. To avoid disclosing the location of an automatic weapon prematurely, the Bren is fitted with a switch giving semi-auto fire.

With the change-over to the new .303 cartridge, the rear sight (a peep) was zeroed at 200 yards, and is raised in 50-yard clicks by turning the range drum on the left. As the sight leaf rises, the readings are exposed on the drum aperture. Maximum reading is 2000 yards.

In the British revision, the gas-port was moved back from the muzzle, and a handle added under the butt to hold the hinged butt-plate firmly down on the shoulder. The total weight was brought up to 22 pounds with folding bipod. In a defensive position, a 2 8-pound tubular tripod can be added. For anti-aircraft use, this tripod extends so that fire can be delivered with gunner standing. For effective AA protection of marching columns and vehicles, this tripod is mounted in a truck. Lately, an elaborately counter-sprung and balanced mount with seat is available for certain vehicles.

The above and other changes brought the weight of the Bren up, and the production engineering down. For some time the Royal Small Arms Factory had a terrible time turning out the Bren, and as late as 1939 its issue was still unsatisfactory. Since the war began, the former farm machinery factory dele-gated to build them in Canada has had another Bren-building nightmare, but in the end managed to get production flowing.

Fortunately, the Bren was not deliberated over so long that a shortage should really affect Britain's war effort. In feeling the war pressure and in acting upon it before America, England gained a significant lead. That is not saying that the light machine gun situation is so excellent that the old 27-pound Lewis light machine gun (which the Bren displaced) has not come into wide use again. Airdrome defense forces, Home Guard, Navy, Australians, Burma Defense Forces and merchantmen find great use for it. Usually it has the characteristic 47-round pan magazine and cylindrical radiator around the barrel. Frequently when only short AA bursts are required, soldiers on armored cars in the desert and sailors at sea have stripped off the radiator and made a lighter, handier weapon.

So great is the shortage of automatic weapons for miscellaneous purposes that even the old cavalry light .303 Hotchkiss may be seen. Americans will recognize in this 30-round strip-fed Buck Rogers rocket pistol what we used to call the Model 1909 Benet-Mercier light machine gun. Definitely antique, it may be found in Australian cavalry outfits, in Australian training camps, and in the Home Guard and on merchantmen. Americans who recall the unfair criticism leveled at our Benet-Mercier when ill-trained personnel failed to operate it, may hope that the men who receive these cast-off but efficient little guns have been sufficiently instructed to use them. If not, the crews will be better off using rifles.

In the concluding portion of "British Lion at Bay" Garrett Underbill will cover all of the remaining weapons of the British Army, giving RIFLEMAN readers the first complete article on British weapons to appear in the U. S.