The American target shooter still may be having a few difficulties getting what he wants, but some of the boys in other lands, who have just as ardent a love for target shooting, really know what troubles can be. Take Denmark, for instance.

On a military mission to Denmark in late summer of 1945, I, was being driven from Copenhagen to the Mosede Proving Ground. It was a lovely day and my fellow passengers, all civilian executives of a large Danish plant, were telling me of prewar Denmark. Riding down the coast, we were attracted by a familiar sound overhead. Looking up, we saw a beautiful flight of wild ducks heading South. A plant, director sighed audibly.

"They're flying early," he said, sadly. "I wish I had my guns back."

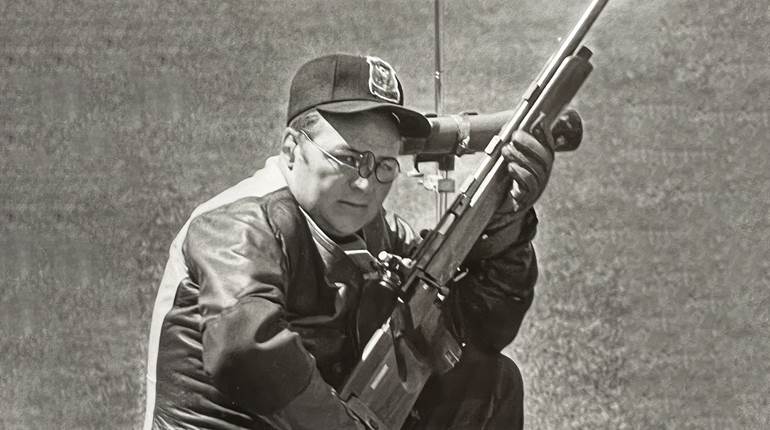

Another of my good friends, Erik Saetter-Lassen, a captain of the Royal Danish Air Force, sub-director of the Madsen (automatic weapons) plant in Copenhagen, and former Danish small-bore rifle champion, told me the real story of Danish shooting—or lack of it.

Besides the hunting of birds and small game—there is little big game in Denmark—the sport of rifle shooting has always figured prominently among shooters in all walks of life. There are two organized groups of riflemen, the Union of Danish Riflemen and the Association of Riflemen and Gymnasts. Their competition was both national and international. The short distance between Denmark and Norway, Sweden and Finland made possible frequent team visits to nearby countries.

On the ninth of April, 1940, Germany invaded the country of King Christian, placing nearly everything under military law. Within a few days an order was issued prohibiting all kinds of sport shooting.

Denmark, like many other foreign lands, had long required the registration of all kinds of firearms except military weapons. The invaders promptly confiscated records and set up headquarters in various centers, chief of which was the Shell Oil Building in Copenhagen  taken over by the Gestapo. They publicly proclaimed that the Danes must immediately turn in all weapons, with severe penalties for failure to do so. Holding Danish police registration records, they were in a position to enforce their demands.

taken over by the Gestapo. They publicly proclaimed that the Danes must immediately turn in all weapons, with severe penalties for failure to do so. Holding Danish police registration records, they were in a position to enforce their demands.

The Danes loved their late King Christian. He had a way of ignoring the Germans and forcing many of his demands for a small amount of freedom for his peoples. As a result of his pressure, members of the two shooting organizations were permitted to retain their small-bore target rifles. They were also permitted limited practice. It is believed that Denmark was the only invaded country to receive such permission.

Naturally Danish riflemen and target shooting activities were under extremely rigid control, but the obstinate Danes kept shooting until August 1943. At that time, the Danish government, taking exception to the heavy and increasing demands made on them and their resources by the invaders, suddenly refused any kind of cooperation with the Germans. As a result, the officers of the Danish Army and Navy were placed under arrest and an order went out prohibiting all kinds of shooting.

The seizure of registered rifles followed immediately, and in September 1944 the Gestapo captured hidden police records, not previously turned in, of other sporting weapons. The weapons were picked upand the lot was shipped to Germany. Naturally all available ammunition went with the guns.

When Germany surrendered and the last invaders left their soil, Danish sportsmen and riflemen found themselves stripped of their weapons. But the shooting fan never gives in.

There is only one good gun plant in Denmark—the. Schultz & Larsen factory in Otterup, on the middle island of Fyn. The plant is old—Larsen rifles antedate the American Civil War—but their precision match rifles are known throughout the world. Although the Germans had closed the plant during the war—it was a sporting rifle firm, retooling for military production was impossible, and the Danes refused to produce for the Germans—limited production began again in 1946.

The demand for the Schultz & Larsen product is high in Denmark, but the American shooter is not confronted with the headaches of the Danes. In order to keep the plant running, the plant imports steel. In order to keep steel coming, they are compelled to export their guns. Only a tiny percentage of their product is permitted to be sold to Danish riflemen.

By mid-summer 1947, Schultz & Larsen were producing two models of rifles, the low-priced number in .22 caliber selling at Kroner 125 (about $27.50 at current exchange) and their famous competition rifle, also a .22, selling for Kroner 500 (about $100).

I have one of these rifles—a heavy-barrel, falling-block, high sidewall number with a heavy stock. With a 31-inch barrel, Redfield-type micrometer extension rear sight, a hooded front sight with removable inserts, and an adjustable aluminum buttplate, the rifle weighs 13 pounds 4 ounces. I picked it up in Germany, and on a visit to the United States in 1946, Captain Saetter-Lassen looked it over fondly. "It's a good rifle," he murmured, "I had one like it ..."

The captain tells me that American match .22 ammunition has been the favorite among Danish riflemen for a generation. Yet, lack of foreign exchange prevents the Danes from buying the good brands they need.

Denmark does not make .22 ammunition. In 1939, .22 ammunition imports of that country, all types from the regular .22 short to match .22 long rifle, ran over nine million kroner—about two and one-quarter millions of dollars. This represents an estimated 300 million rounds.

In 1946, with the shooting game slowly reviving, Danish imports of .22 ammunition ran only about $200,000, or about fifteen million rounds—with today's demand far in excess of 1939. Little of the imported ammunition came from the United States because of the shortage of American dollars.

In June 1947, despite the shortage, there was little hiking of prices on ammunition such as was noted in this country during 1946. Ordinary .22's sold in Denmark for about thirteen dollars a thousand. Match grade .22 long rifle, mostly ICI (British), sold at eighteen dollars. With these handicaps, the Danish small-bore shooter is trying his best to keep in training. Where the; American shooter would consume 500 rounds in practice, the Danish rifleman must be content with one ten-shot string. He does not waste ammunition in fouling and for sighters.

The Danes are not discouraged. They are fighting hard to get back on their feet. And they sadly recall the 'advantages' of firearms registration, which, I am told, was also 'to prevent crime.'