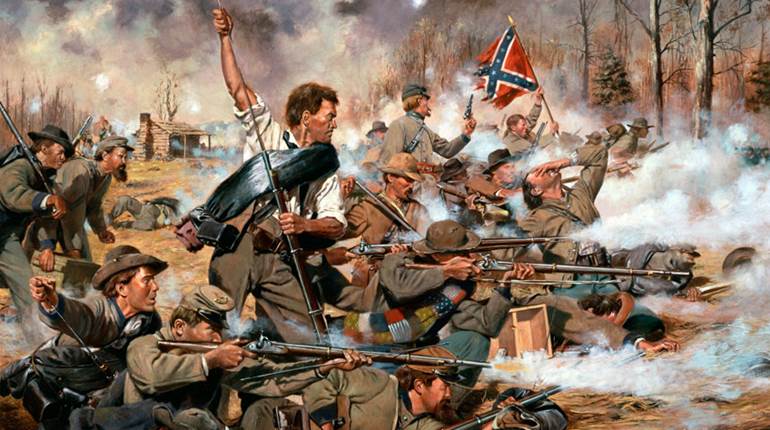

On July 1, 1863, the 6th Wisconsin Infantry—part of the “Iron Brigade”—was rushed to stem the advance of Brig. Gen. Joseph Davis’ troops. The result was fierce hand-to-hand combat over the colors of the 2nd Mississippi Infantry. By Gettysburg, about 90 percent of the infantry on both sides was using modern rifle-muskets.

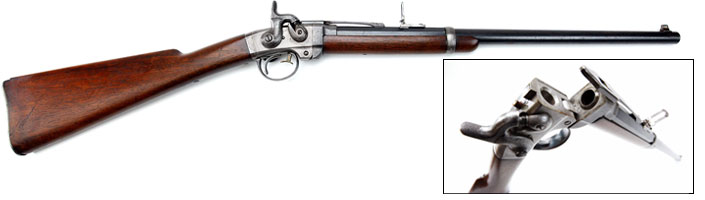

The lieutenant grabbed his sergeant’s Sharps carbine, dropped the lever, slipped a linen cartridge into the open chamber, closed the action, cocked the hammer and capped the nipple. Using a fence rail for a rest, he jacked up the sights to what he thought an appropriate height for the range and squeezed off a shot at the advancing Confederate infantry, some 600 yds. away. The bullet hit the ground in a puff of dust halfway to the Rebs. He had miscalculated, but had accomplished what he set out to do. Forever after, 2nd Lt. Marcellus E. Jones of Milton, Ill., and the 8th Illinois Cavalry could claim the honor of firing the first shot of perhaps the greatest of American battles: Gettysburg.

Unlike most of the encounters of the first two years of the Civil War, including Manassas and Antietam, Gettysburg involved significant cavalry action at both its outset and its end. As dawn broke on July 1, 1863, Brig. Gen. John Buford’s cavalry division, including Lt. Jones’ regiment, was deployed on the ridgelines north and west of the little Pennsylvania town. Buford’s job was to seek out the Army of Northern Virginia while shielding his own Army of the Potomac from prying enemy eyes. That morning both armies, primed for a climactic, perhaps war-ending, fight, were converging via roads that radiated outward from a Gettysburg hub.

The campaign began in the wake of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s “perfect battle” triumph over Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker at Chancellorsville in May. As with Second Manassas the previous year, Chancellorsville provided Lee with a springboard for an invasion of the North. The Confederate commander intended to take the war out of ravaged Virginia, supply his army off the enemy’s land, encourage anti-war elements in the Union states and perhaps capitalize on unforeseen events. Hooker followed, too tentatively for President Abraham Lincoln, who, given an opportunity, replaced him with Maj. Gen. George G. Meade.

As battle drew nigh, both forces began to concentrate near Gettysburg, where, following Jones’ shot, Buford’s horse soldiers traded fire with Confederate infantry skirmishers. The Union cavalry managed a gradual fighting withdrawal, delaying the enemy while federal foot soldiers marched to the rescue. Union infantry, the First and then the Eleventh Army Corps, arrived in the nick of time, halting the Rebel advance. As the day wore on, however, more Confederates poured into the fight and the advantage swayed back and forth until the Union line broke and defeated Yankees streamed back through Gettysburg to the high ground on Cemetery Ridge, where they rallied and set up a defensive position.

During the night, reinforcements arrived for both sides and July 2 found the Army of the Potomac deployed in a “fishhook” line, anchored on its barb end at Culp’s Hill. That afternoon Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles advanced his Third Army Corps from its position on the shank along Cemetery Ridge forward to the Emmitsburg Road, his left flank hanging in the breeze at an ancient glacial rock formation. Sickles, who thought he was improving his tactical situation by advancing, was unaware that Lee had planned an attack on the Union left. The assault, delayed by organizational difficulties, was launched late that day, and in heavy fighting at sites that would forever after be part of the American military iconography—Devil’s Den, Little Round Top and the Wheatfield—the stubborn federals were driven back to Cemetery Ridge, from where an exhausted Confederate force could push them no farther. An evening strike at Culp’s Hill failed as well.

July 3 opened without major combat, but an afternoon artillery duel preceded the disastrous Confederate infantry assault known forever afterward as “Pickett’s Charge” after Maj. Gen. George Pickett, who commanded one of the three divisions. A lesser known fight, of interest to students of firearm technology, occurred some three miles behind the Union lines as Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart, moving his cavalry division to exploit any advantages gained by the infantry attack on the Union center, engaged a federal cavalry division under Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg in a series of dismounted firefights and conventional saber charges.

Gettysburg was a small arms watershed, with every type of firearm technology available during the war, from obsolete muzzleloading smoothbore muskets to more modern rifle-muskets, breechloading, single-shot rifles and carbines, revolvers, sabers, long-range target rifles, and state-of-the-art repeating rifles in action somewhere on the battlefield during the three days of fighting.

Gettysburg was a small arms watershed, with every type of firearm technology available during the war, from obsolete muzzleloading smoothbore muskets to more modern rifle-muskets, breechloading, single-shot rifles and carbines, revolvers, sabers, long-range target rifles, and state-of-the-art repeating rifles in action somewhere on the battlefield during the three days of fighting.

By mid-1863, the Union cavalry was a heavily armed force, with each trooper carrying a breechloading carbine, saber and cap-and-ball revolver. At first glance, dismounted horse soldiers, with their faster-firing shoulder arms backed up by six-shot handguns, might seem to have an advantage over infantrymen armed with single-shot muzzleloading rifle-muskets. In reality, however, Civil War cavalry did not engage in stand-up fights with infantry, as the mounted arm’s tactical role was quite different than that of foot soldiers. In addition to not being schooled in infantry tactics, a dismounted cavalry force immediately lost a quarter of its potential firepower, as every fourth man was required to hold horses behind the skirmish line.

Breechloading carbines had long been preferred for cavalry, as they could be fired and reloaded on horseback. Such use in the Civil War was rare, however, and carbines were primarily used for dismounted skirmishing. In addition to the Sharps, the men in Buford’s cavalry screen were equipped with a variety of carbines, including the Burnside, Sharps & Hankins, Gallager, and Smith and Merrill. The guns fired .50 to .54-cal. cartridges with 40- to 45-gr. powder charges. All, save the Smith and Merrill, were operated by lowering a trigger guard lever to expose the chamber for loading. All but the Sharps & Hankins used semi-fixed ammunition—a cartridge containing powder and bullet with priming supplied by a percussion cap placed on an external nipple. Civil War carbines used a variety of non-interchangeable specialty cartridges of different shapes and materials, some of which acted as breech seals, although the Sharps and Merrill depended on mechanical breech sealing. Such ammunition diversity proved an ordnance officer’s nightmare, especially when, as was often the case, a unit was armed with several varieties of carbines.

The sturdy and accurate Sharps used a combustible .54-cal. linen cartridge (which replaced the old paper cartridge that allowed loose powder to migrate into places where it could explode), and was the most common and popular carbine. The Gallager chambered a .52-cal. brass cartridge that had to be manually extracted after firing, often with great difficulty, and was variously described as “inefficient” and “not equal to a bar of iron” in field evaluation reports by the men to whom it was issued.

The .54-cal. Burnside, as durable and accurate as the Sharps, fired a tapered brass cartridge loaded in a breechblock chamber that tilted upward and featured a primitive bump extractor that jarred the fired case loose on opening the action. The .50-cal. Smith employed a rubber cartridge that expanded to seal the chamber on firing, and then shrank for easy manual removal. A well regarded gun during the war, it has remained so in original and reproduction form among carbine shooters in the North-South Skirmish Ass’n. The .54-cal. Merrill used a paper cartridge which, like the Sharps paper rounds, was fragile and often broke up in cartridge boxes due to the “jouncing” effect conveyed by trotting horses. The majority of respondents to a late war survey of carbine effectiveness considered the Merrill “worthless.”

The most modern gun on the field that day was the Sharps & Hankins designed by Christian Sharps after he left the company that produced carbines bearing his name. It fired a .52-cal. rimfire cartridge with powder, bullet and priming compound all in one convenient water- and jounce-proof copper package. Most Sharps & Hankins carbines were purchased by the navy, but New York bought some as well, apparently including those carried by three companies of the 9th New York Cavalry at Gettysburg.

Historical myth has long held that Buford’s troopers were armed with seven-shot repeating Spencer carbines on July 1, and credits the firepower of the Spencers with delaying the Confederate advance. In reality, the fighting that morning was between loosely deployed skirmish lines on both sides. The cavalry presence forced the Confederates, who did not know where the Union infantry was, to deploy into line of battle, which took up the time needed for Union infantry to arrive. Casualties were light on both sides. One cavalryman reportedly fired only a dozen rounds from his carbine all morning.

Spencer repeating rifles (not carbines, which would not be produced until October 1863) firing rimfire cartridges were indeed used in combat at Gettysburg, but not until the July 3 cavalry fight. General Gregg’s division included Brig. Gen. George A. Custer’s Michigan Brigade. The 5th and part of the 6th Michigan Cavalry had recently been issued Spencers, and the 6th had used them for the first time in the eastern theater of war in a skirmish at Hanover, Pa., on June 30.

When he encountered Gregg, Gen. Stuart ordered the 34th Virginia Cavalry Battalion to dismount and hold the Rummel farm. After two regiments with Sharps and Burnside carbines failed to dislodge the 34th, the Spencer-armed 5th Michigan was ordered to drive the Virginians out. The 34th was actually a mounted infantry outfit armed with a mixture of muzzleloading Enfield and Richmond rifle-muskets and shorter-barreled Richmond rifle-muskets

purpose-built for such service, as well as revolvers. The outcome of the ensuing firefight between two approximately equal forces armed with old and new technology was ambiguous. The Wolverines had to withdraw when they ran low on ammunition, but the Virginians, though holding the field, suffered an astounding 75 percent casualty rate compared to the 8.7 percent rate suffered by the Michigan men—statistics that did not bode well for a Confederate future.

In the wake of the dismounted firefight, Stuart ordered a mounted charge and the subsequent series of wild melees saw sabers and cap-and-ball revolvers, mostly .44-cal. Colt Model 1860 Armies, used at point-blank range. One soldier remembered that handguns were “discharged … into the very face of the foe” as the horsemen slammed into each other. Most of the 7th Michigan Cavalry’s casualties that day were caused by sabers and revolver bullets. Confederate Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton was severely slashed in the head twice by troopers from the 1st New Jersey Cavalry before the Rebels retreated, ending the fighting for the day.

Artillerymen were issued a limited number of revolvers, mainly to dispatch mortally wounded horses, although they were used on occasion to defend a battery. Infantry officers usually carried personally owned handguns, more as badges of rank than offensive arms. At Gettysburg some of those handguns were indeed fired at the enemy, however. In the Wheatfield fight Capt. Garrett Nowlen of the 116th Pennsylvania used his revolver in close action, and Confederate Col. Franklin Gaillard of the 2nd South Carolina remembered that the fighting “was so desperate I took two shots with my pistol at men scarcely thirty steps from me.”

Although cavalry action at Gettysburg was extensive in comparison to previous major battles, the infantry bore the brunt of the fighting over the three days of combat. Blockade runner deliveries of British Pattern 1853 Enfield pattern arms coupled with captures at Chancellorsville and a small but steady domestic production, primarily at Richmond Armory, resulted in an Army of Northern Virginia that was, according to Confederate Col. Edward P. Alexander, 90 percent armed with rifled .54- and .58-cal. arms as it entered Pennsylvania. An even higher percentage of the Army of the Potomac’s soldiers were armed with imported Enfields and Austrian Lorenzes and Model 1861 Springfield rifle-muskets from vastly expanded armory production and deliveries from contractors.

With the exception of specialized units in the Army of Northern Virginia, marksmanship training had improved little in either army since the war began. Ironically, the 21st New York infantry, which took shooting practice seriously at ranges up to 500 yds., was mustered out of the service prior to the Gettysburg campaign. The 121st New York, 15th New Jersey and other regiments conducted some familiarization firing at various known distances in the spring of 1863, but ignored range estimation and marksmanship basics.

Occasional attempts at long-range fire by line outfits at Gettysburg, including a volley aimed by the 56th Pennsylvania at the 55th North Carolina at an undetermined distance on July 1, proved ineffective. Brigadier General Hobart Ward, commanding a brigade on Houck’s Ridge between the Wheatfield and Devil’s Den on July 2, ordered his men to hold fire until the Rebels were 200 yds. away, which, following modern verification by range-finder at various spots on the field, turns out to be the average infantry engagement range at Gettysburg.

Although the rifle-musket was predominant on the Gettysburg battlefield, there were older .69-cal. smoothbore muskets in service in some regiments on both sides. When the 6th Minnesota infantry charged the railroad cut west of town on July 1, a number of the Badgers suffered buckshot wounds from smoothbore “buck-and-ball” rounds. One Yankee struggling with the 2nd Mississippi’s color bearer for that regiment’s flag had “a ball and three buckshot … through the skirts of my frock coat … .” Around 10 percent of the arms captured by the Union First Army Corps that day were smoothbores, reflecting the accuracy of Col. Alexander’s arms estimate.

The New York and Pennsylvania regiments of the Irish Brigade used their smoothbores to good effect when they closed with the enemy on the slope of a stony hill adjacent to the Wheatfield, but perhaps the most significant smoothbore story at Gettysburg was that of the 12th New Jersey Infantry. In their position on Cemetery Ridge, the Jerseymen disassembled their buck and ball cartridges on July 3 while awaiting Pickett’s charge, creating massive ad hoc charges of fifteen or more buckshot for their Model 1842 muskets. The men of the 12th laid low until Confederate infantry came within 50 yds. of their position, then delivered a massive volley into the 26th North Carolina, a regiment already battered on July 1, virtually destroying what remained of the unit. Years after the war, when the veterans of the 12th erected their Gettysburg monument, it was surmounted by one large sphere and three small ones—and inscribed with the words “buck and ball.”

The combat role of Civil War sharpshooters is often confused with that of modern snipers. Although some were detailed to what could be called long-range sniping duty, most sharpshooters were intended to be expert skirmishers, deployed in front of a main line of battle in loose formation in advance or retreat. The Army of Northern Virginia formed a number of brigade sharpshooter battalions, selected from a brigade’s best shots, in early 1863. Those men were armed with rifle-muskets, but well trained to use them effectively, and did so in the Gettysburg campaign, delivering heavy harassing fire on Cemetery Ridge from the area of the Bliss barn and the town’s rooftops. A South Carolina battalion commander estimated that his men fired more than 200 rounds each on the morning of July 3.

The combat role of Civil War sharpshooters is often confused with that of modern snipers. Although some were detailed to what could be called long-range sniping duty, most sharpshooters were intended to be expert skirmishers, deployed in front of a main line of battle in loose formation in advance or retreat. The Army of Northern Virginia formed a number of brigade sharpshooter battalions, selected from a brigade’s best shots, in early 1863. Those men were armed with rifle-muskets, but well trained to use them effectively, and did so in the Gettysburg campaign, delivering heavy harassing fire on Cemetery Ridge from the area of the Bliss barn and the town’s rooftops. A South Carolina battalion commander estimated that his men fired more than 200 rounds each on the morning of July 3.

Perhaps the most famous Gettysburg incident attributed to Confederate sharpshooters was the death of Maj. Gen. John Reynolds on July 1, but a close examination of that incident by Gettysburg scholar Dr. David Martin disproves several such claims and concludes that Reynolds, who was indeed too far forward for a general, was hit by fire from the opposing line of battle. The scope-sighted British Whitworth rifle is often associated with Southern sharpshooters, but despite the unsubstantiated postwar claim of one veteran, it is unlikely any were in use at Gettysburg. Likewise, the long-told story of a heavy New England-made target rifle allegedly discovered in a Confederate position at Devil’s Den after the battle, despite the fact that the gun was on display at the battlefield museum for many years, is also, to be kind, extremely suspect.

Although there had been proposals in the spring of 1863 to create sharpshooter battalions in the Union Army, the plan never materialized. There were, however, several regiments and companies of sharpshooters distributed unevenly through the Army of the Potomac. The two regiments of Berdan’s sharpshooters, both assigned to the Third Army Corps, were armed with Sharps rifles, with one heavy barrel, long-range rifle per company carried in the regimental supply wagons for retrieval in static combat situations. Parties of Berdan’s men did good work on the southern edge of the Gettysburg battlefield, particularly in the fight for Little Round Top. Interestingly, when four companies of Berdan’s First Regiment, supported by the 3rd Maine, encountered Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox’s Alabama brigade on a reconnaissance in force into Pitzer’s Woods on the morning of July 2, the resulting 15-minute firefight, in which the sharpshooters expended 95 rounds per man, cost the Alabamans only 56 casualties.

The army’s two companies of Massachusetts sharpshooters had disposed of most, but not all, of their heavy state-supplied W. D. Langdon target rifles in exchange for Sharps rifles after Antietam, but also counted a few Merrill rifles in their ranks at Gettysburg. When Rebel sharpshooters firing from Gettysburg rooftops decimated a party of New York skirmishers, the First Company was deployed in response, and killed and wounded a significant number of their Confederate counterparts. Capt. Richard S. Thompson of the 12th New Jersey recalled watching some Massachusetts sharpshooters armed with scope-sighted target rifles firing from Cemetery Ridge at Confederate sharpshooters in the Bliss barn. Thompson’s description of their tactics, with a three-man team including a shooter and spotter, bears a striking similarity to modern sniper techniques.

Although many Confederates thought they had gained, at worst, a draw in the immediate aftermath of the battle, Gettysburg would prove, in retrospect, to indeed be the “high water mark” of the Confederacy. Lee withdrew his battered army south, with Meade tentatively following. Almost two years of bloody combat remained, but from then to the end of the war, the Army of Northern Virginia would remain on the defensive, hoping for a game-changing event that would never come.

In the years after the battle there were other contenders for first-round honors, but none seriously challenged Lt. Jones, who left the Union Army as a captain in 1865. For decades thereafter, until his death in 1900, Jones no doubt regaled the members of Grand Army of the Republic E.S. Kelly Post No. 513 in Prospect Park, Ill., with tales of his historic Sharps shot. At one point he and some comrades came back to Gettysburg and erected a small monument on the spot, then private property, now within the National Military Park boundary. It still stands.