10/31/2012

By 1859 the stage was finally set for accurate long-range shooting. But the Crimean War had showed that the British Army had not yet figured out how to train riflemen—as opposed to musketeers. Massed musket fire was a drill movement; accurate rifle shooting was a personal skill.

Britain’s Volunteer Movement rifle corps was a grass-roots response to its concern for the national defense. Units sprang up around the United Kingdom, but most volunteers had no rifle-shooting skills either. In the fall of 1859, representatives of the Hythe Volunteer Force and the London Rifle Brigade met at the home of Earl Spencer and proposed a National Rifle Association, for “the promotion of Rifle Shooting throughout Great Britain.”

Britain’s NRA was formed before the end of the year. Lord Spencer solved the problem of where matches would be held by inviting the NRA to use his front yard, Wimbledon Common. On July 2, 1860, the opening shot of the first match was fired by Queen Victoria herself, and the winner of the long-range competition would be awarded the Queen’s Prize.

In 1860 America had national defense concerns, too, and much larger ones. Early in the Civil War, there was a strong feeling in some quarters that the press was undermining Union efforts. In response, the United States Army and Navy Journal and Gazette of the Regular and Volunteer Services was launched in June 1863. William C. Church, who had been a newspaper editor, resigned his captaincy in the Union Army to manage the new publication. It would become an encyclopedia of things military, emphasizing rifles and marksmanship.

The Civil War sped the development of breechloading rifles and center-fire ammunition, but it did little to improve the state of rifle marksmanship. In 1870 and 1871, Church published six installments of George Wingate’s Manual for Rifle Practice. (Gen. Wingate noted, “The general ignorance concerning marksmanship which I found among the soldiers during the Civil War appalled me, and I hoped that I might better the situation.”) Church also hosted a meeting at the offices of the Army and Navy Journal on Aug. 19, 1871, to discuss marksmanship. His group researched target shooting and drafted rules and bylaws, and then, on Nov. 17, 1871, they incorporated the National Rifle Association of America.

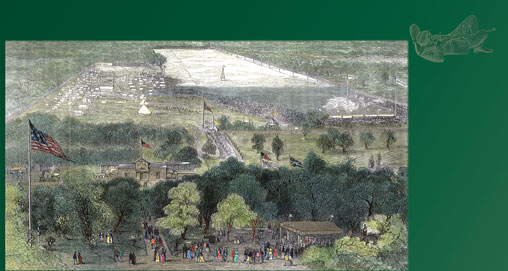

Legislative lobbying is a critical function of the modern NRA. In America, it began on Feb. 7, 1872, when the NRA drafted a bill requesting a $25,000 grant to build a shooting range. The bill passed, and in July the NRA purchased 70 acres of moorland on New York’s Long Island from a family named Creed. The American NRA’s first annual matches were held at the new Creedmoor Range on Oct. 8, 1873.

Arthur Blennerhassett Leech was an Irish attorney who made his fortune in Bombay. He returned to Ireland around 1860 and then moved to London. A dedicated rifleman, Leech established the London Irish Volunteers, in which he gave himself the rank of major. He was also a client of the Dublin firm of John Rigby & Son, which by 1866 had a shop in London, too. In 1867 Leech transformed the Dublin Shooting Club into the Irish Rifle Ass’n, and he successfully petitioned to allow the Irish team to shoot for the Elcho Shield, a trophy at Wimbledon.

A Rigby rifle had taken the Queen’s Prize in 1865; in 1873 an all-Rigby-equipped Irish team captured the Elcho Shield for the first time. Leech was the captain of that team and John Rigby a member. Buoyed by this feat, Leech wrote to the editor of the largest newspaper in the United States, the New York Herald:

“Sir,

“In matters of enterprise your name occurs to me before any in America, as most likely to bring to a successful issue an International Rifle Match, which I beg to propose between Ireland and America. At the great meeting held annually at Wimbledon, a team of eight Irishmen shooting with Irish-made rifles, this year beat the picked eights of England and Scotland. As the great American nation has long enjoyed a world-wide reputation for skill in rifle shooting, it occurs to me that the enclosed challenge from Irish riflemen, now the champions of Great Britain might be accepted, and if so, a team would be organized to visit the United States in the summer of 1874. I enclose an account of the match at Wimbledon, and the proceedings on the reception of the Irish Eight in Dublin.

“I have the honour to remain,

“Your faithful servant,

“Arthur B. Leech.”

The match would be comprised of 15 shots at 800, 900, and 1,000 yards from any unsupported position. The rifles could weigh no more than 10 pounds, and both telescopic sights and “hair” (less than a 3-pound pull) triggers were prohibited. American team members were to be native-born and their rifles of American manufacture.

Leech’s letter was published on Nov. 22, 1873. George Wingate, who was both the secretary of the NRA and president of the Amateur Rifle Club of New York City, accepted the challenge. The match was set for Sept. 26, 1874, at Creedmoor. The Irish would use Rigby muzzleloading match rifles, while Remington and Sharps developed breechloaders for the home team. Smokeless propellant was not yet in use.

The Irish team, accompanied by dignitaries that included the Lord Mayor of Dublin, set sail on Sept. 6, 1874. In New York the Irish went through a whirl of high-profile social engagements before practice started. On September 26, the day of the match, the winds were light, the sky clear, and a crowd of 8,000 had gathered. The first stage, at 800 yards, took about 90 minutes. The American team scored 326 points to the Irish 317. Herald and other newspaper reporters telegraphed the results to their offices, where they were posted on public bulletin boards, and from there they were relayed to Britain by cable.

Then it was time for lunch and speeches. Leech surprised the crowd by announcing that he would like to leave a souvenir of the Irish team’s visit and uncovered a large and ornate silver tankard in the shape of “the old towers of Ireland.” It was inscribed: “Presented for Competition to the riflemen of America, by Arthur Blennerhassett Leech, Captain of the International Team of Riflemen, on the occasion of their visit to New York.” The cup was graciously accepted by Col. Wingate. It became a perpetual trophy for the NRA of America, and is still competed for today.

The competition resumed. At 900 yards, the score was Ireland 312, America 310. The Irish lead would have been greater but for an error by one of their members. J.K. Millner bull’s-eyed his first shot at 900 yards—but on the wrong target, thus earning a zero on the shot. Total scores now were 636 for America, 629 for Ireland.

At 1,000 yards, the Irish caught and passed the Americans. The match came down to the last shot, by Col. Bodine of the United States. Bodine was about to sip a fizzy drink when the glass bottle exploded in his hand. In spite of the bleeding, he got into position and fired the decisive shot. A white disk rose in front of the target: bull’s-eye! The Irish had prevailed at the distance, 302 to 298, but lost the match by just three points—931 to 934. John Rigby posted the highest score for the Irish, but the American team had the Leech Cup.

A week later, the NRA held its own long-range match, which provided the Irish a chance to recoup. Again the scoring was very close, but this time the Irish won, by six points. The high overall individual was John Rigby.

The Americans cleaned the fouling from their barrels after every shot, while the Irish fired the entire match without cleaning their muzzleloaders. This led to an impromptu 1,000-yard match between Rigby rifles and Sharps. The Herald reported: “Mr. John Rigby’s challenge for a trial of the comparative merits of the famous Irish rifle with the American breech-loader, 25-rounds without cleaning, virtually proved no contest. The lowest Irish score was higher than the best American.”

The score was 321 to 201, with John Rigby again posting the highest numbers. Rigby then personally challenged one of the top American shooters, Gen. T.S. Dakin, to an unusual competition: five shots from the standing position at 1,000 yards Rigby outshot Dakin, 11 points to 7.

The matches at Creedmoor generated huge interest. Invitations came to the Irish team from across the United States and Canada. They visited Niagara Falls, Montreal, New Orleans, Louisville, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia and Chicago.

Chicago was memorable. The Irish stayed at the Palmer House, which Leech described as “the finest hotel in Chicago, and perhaps in America”—rooms cost $4 and meals were available at all hours. President Grant and his wife were also at the Palmer House for the marriage of their son. “The President having been informed that we were lodged under the same roof as himself, did us the honor of intimating his wish to receive us for the evening,” wrote Leech, adding, “The President gave us a most friendly reception, and conversed with us for some time, expressing his regret that he had been unable to be present on the great occasion at Creedmoor, and speaking of the performance of both teams in terms of the highest praise.”

A member of Leech’s party noted: “In the evening Major Leech spent some time with the President and Mrs. Grant, and afterwards introduced us to General Custer and others on the President’s staff. The general, who is an enthusiast about rifle shooting, here accepted a highly finished Rigby match rifle, the gift of Major Leech ... .”

In 1875 Custer and some of his staff posed for photographs at Ft. Lincoln, Dakota Territory. One photo, reproduced in John S. du Mont’s Custer Battle Guns, shows what appears to be the Rigby on a rack in Custer’s room. As the world knows, on June 25 and 26, 1876, Custer and his entire command died at the Little Big Horn River in the Montana Territory.

Custer’s wife Elizabeth—Libbie—lived until 1933. She gave at least two of her late husband’s firearms to their godson, George L. Yates, whose father died with Custer. One was a Webley .44-cal. revolver that Lord Berkley Paget had presented to Custer in 1869 in thanks for a Kansas buffalo hunt. The other gift was the Rigby, for which Yates thanked his godmother in a letter dated Sept. 5, 1913.

In her book Boots and Saddles, Libbie Custer describes her husband’s firearms as “a collection of pistols, hunting knives, Winchester and Springfield rifles, shotguns and carbines, and even an old flintlock musket.” Could the Rigby, with its tall hammer and fixed breech, have been the “flintlock?” Perhaps somewhere in America, forgotten in a gun safe, is the Rigby match rifle that Arthur Leech gave to George Custer as a result of the kindness shown to a group of visitors by President Ulysses Grant.

Arthur Leech retired from the Irish Rifle Ass’n in 1885. When he died, in 1892, The Irish Times wrote: “Every Irish rifleman who may enter into friendly competitions in England or America in the future will, like those in the past, have the best reason to cherish the memory of Major Leech.”

Today the Creedmoor Range is gone, swallowed up by the Borough of Queens, but the National Matches are still shot, now at Camp Perry in Ohio. The Leech Cup, the oldest target-shooting trophy in the United States, is hotly contested every year. The match now is fired at 1,000 yards, prone and unsupported, with iron sights, and its 20 shots are fired with bolt-action or semi-automatic rifles. But the change that would surprise Leech, Church and Rigby the most is the nature of the competitors. Those first shooters were a whiskered bunch. In 2011 the competitors included shooters named Maureen, Jennifer, Anette and Cindy.

As it did in 1874, victory in the 2011 Leech Cup hung on the last shot. Nancy Tompkins, of Prescott, Ariz., edged out the second-place finisher by one point. Since 1995 Tompkins has won the Leech Cup six times—and lost it once to her daughter, Michelle.