The artillery barrage began at 0530 hours when more than 600 German guns opened all along the line. It was Saturday, Dec. 16, 1944—the opening day of the massive offensive known to the Germans as Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein (or Operation Watch on the Rhine). To the 800,000 American soldiers who ultimately prevailed against the enemy onslaught, it was known as the Battle of the Bulge. Conceived as a means of recapturing the port city at Antwerp, the German plan called for a massive offensive that would punch through American lines in the remote Ardennes forest area of northern Luxembourg and southeastern Belgium. They hoped to drive a wedge between British and American Army Groups. Hitler hoped to force the British and the Americans to reach a separate peace with Germany. Central to the success of the operation would be the rapid movement of the mechanized elements of the Sixth SS Panzer Army, which would advance from the Losheim Gap in Germany to the banks of the Meuse River in the vicinity of Liège and then turn to the north to drive toward Antwerp.

While the attack’s spearhead overwhelmed many American fighting units, others held their ground heroically and slowed the German advance. A platoon from the 394th Infantry Regiment, 99th Infantry Division held off German paratroopers at Lanzerath for almost the entire day before being overrun. The 2nd Infantry Division held the line at Elsenborn Ridge, and the 7th Armored Division did the same at St. Vith when the Fifth Panzer Army struck. To the south, another dramatic clash unfolded when the 2nd Panzer Division crossed the Our River, entered Luxembourg and slammed into the forward outposts of the 11oth Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division near Clervaux. After struggling with and being delayed by the spirited defenders in these locations, German forces broke out into the maze-like roads of the Ardennes. To make matters worse for the defenders, the attack came amid the dense fog of a winter storm that grounded Allied airpower and reduced visibility to hand-grenade range.

As German units swept through town after town, they took prisoners by the thousands and began committing atrocities. In Honsfeld, they shot 19 POWs. At Büllingen, they shot 59 more. On Dec. 17, grenadiers from the 1st SS Panzer Division’s Kampfgruppe Knittel murdered 11 soldiers from the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion in the village of Wereth. That same afternoon, grenadiers from the division’s Kampfgruppe Peiper gunned-down 86 prisoners from the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion at the Baugnez crossroads near the village of Malmedy.

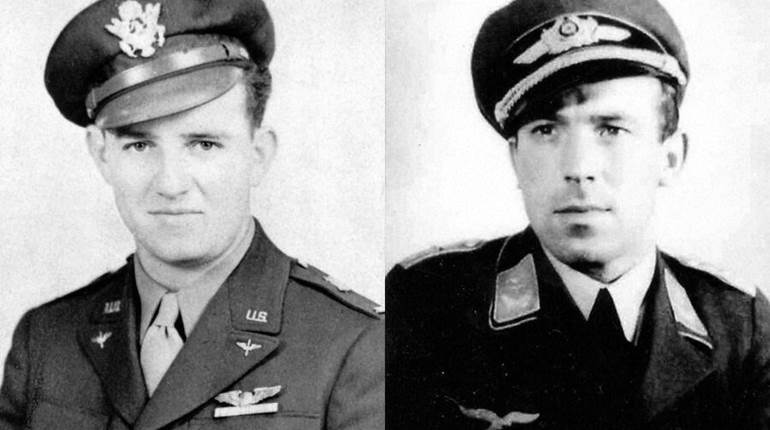

The following day, the 1st SS Panzer Division shot-up a column of American vehicles from the 14th Cavalry Group near the village of Poteau. A series of now-famous propaganda images taken there afterward show the armament typical of German troops in late 1944. In the photographs, SS and Luftwaffe troops can be seen armed with K98k Mauser bolt-action rifles, MP40 submachine guns, MP44 select-fire carbines and MG42 belt-fed machine guns. Surprisingly, one of the SS men in the photos is armed with a Fabrique Nationale 9 mm Hi Power pistol while another is armed with a captured M1 Carbine. The photographic record from elsewhere in the Ardennes reveals an interesting diversity of guns being used during the Battle of the Bulge. German paratroopers can be seen armed with G43 semi-automatic rifles and at least one captured Sten Mk II submachine gun. American soldiers can be seen armed with captured German arms in addition to guns designed by the three Johns: John Browning, John Thompson and John Garand. Although .30-cal. machine guns in both M1917A1 water-cooled and M1919A4 air-cooled versions, Thompson submachine guns and M1 rifles appear most frequently in the combat photography, U.S. Army soldiers can also be seen carrying M3 Grease Guns and Winchester Model 12s.

Although initially thrown into disarray, the American units that reeled in the face of the German breakthrough nevertheless did what they could to oppose the enemy’s advance. On Dec. 18 Kampfgruppe Peiper reached the village of Stavelot a day behind schedule only to find stubborn American defenders. Seeking a spot to get their vehicles across the Amblève River, Peiper’s forces then proceeded to the town of Trois Ponts where retreating U.S. Army combat engineers had already destroyed the bridge. They pushed on to La Gleize and then Stoumont, only to find yet another blown bridge. Although Kampfgruppe Peiper captured the Meuse River bridges at Huy, it would go no further and would ultimately have to abandon its vehicles and retreat. To the south, the Fifth Panzer Army streamed forward, encircling two regiments of the 106th Infantry Division on Dec. 19, capturing more than 7,000 prisoners. It also drove the 28th Infantry Division from Wiltz in northern Luxembourg, entered Belgium and closed in on the crossroads town of Bastogne.

With the XLVII (47th) Panzer Corps approaching the city on Dec. 19, the Army responded to the crisis by rushing elements of the 10th Armored Division and the 101st Airborne Division to its defense. The reinforcement of Bastogne came just in time as three German divisions moved in and surrounded the city by noon on Dec. 21. The following day the German corps commander, General der Panzertruppe Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz, sent a note through the lines demanding the surrender of American forces in Bastogne and threatening to “annihilate” them should they refuse. When that note made its way to the ranking officer present, Brig. Gen. Anthony C. McAuliffe of the 101st Airborne, he replied succinctly: “To the German Commander, “Nuts!” The American Commander.” Despite its ruthlessness, the German assault had not shaken the fighting spirit of the men encircled in Bastogne. However, with all roads in and out of the city cut off by the enemy it had become necessary to send a relief force to break the siege. General George S. Patton’s Third Army, more than 100 miles to the south, received the order to turn to the north and fight through to Bastogne.

As the Third Army began its epic drive north, the fortunes of war began to turn. On Dec. 23 the skies cleared, allowing American air power to begin flying in support of the troops on the ground. By that time the Germans had outrun their supply lines, and shortages of fuel and ammunition created a critical situation. On Christmas Eve the German advance stalled 10 miles short of the Meuse River near Dinant, Belgium. Then during the early evening of Dec. 26, a Sherman tank named Cobra King by its crew from the 37th Tank Battalion reached soldiers of the 101st Airborne near Assenois—breaking the encirclement of Bastogne. Although the German offensive had lost its momentum, it drove a large salient into the U.S. First Army.

In early January 1945, an Allied counter-offensive struck the salient and produced still more intense combat in the bitter cold. At this time, the 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion was attached to the 82nd Airborne Division fighting on the north shoulder of the “Bulge” near Trois Ponts. Pvt. Joe M. Cicchinelli of A Company, 551st was one of those cold, shivering paratroopers, and he looked on as the men of B Company began an attack on the village of Dairomont on Jan. 4, 1945. When that attack ran into enemy machine guns concealed by heavy mist and fog, it began to stall. Cicchinelli’s platoon leader quickly realized that blindly firing into the mist might result in friendly fire casualties, so he gave the only command that made sense: “Fix bayonets!” Cicchinelli obediently drew his bayonet from its scabbard and mounted it on the lug at the muzzle of his M1 Garand rifle. At the command of “Charge,” they all rushed toward the Germans yelling and shouting. “We reached the enemy position, and leaped from foxhole to foxhole, thrusting our bayonets into the startled Germans,” Cicchinelli recalled. It was over in minutes and 64 enemies lay dead on the battlefield. Dairomont had been captured by a handful of determined American riflemen at the point of the bayonet.

Meanwhile on the opposite side of the “Bulge” salient, the 80th Infantry Division attacked the left flank of the German Seventh Army near Ettlebruck, Luxembourg. On Jan. 8, the 1st Battalion, 394th Infantry advanced to a plateau three miles southeast of the city of Wiltz with B Company occupying the tiny farming village of Dahl. As the company moved in, a nine-man squad lead by Staff Sgt. Day G. Turner was sent to establish a flank outpost at Am Aastert, a farm on the northeastern edge of the village. There, Turner’s men dug foxholes in the frozen pasture facing north toward the neighboring village of Nocher, less than a mile away across a gently sloping ravine.

Shortly before noon, German artillery began to fall on Am Aastert and enemy infantry advanced from Nocher into a stand of pine trees in the ravine. When the enemy emerged from the tree line and charged uphill toward the farm, Turner’s men began to drop them with accurate fire from their M1 rifles at 300 yards. Having failed with the first attack, the Germans pounded the farm again with a mortar and rocket barrage that drove the nine Americans from their foxholes and into the farm house.

Under the cover of the renewed barrage, enemy infantry attempted to cross the ravine and overrun Am Aastert again. This time, Turner and his men directed accurate rifle fire on them from open windows on the second floor—repulsing the second assault with heavy German losses. Undeterred, the Germans sent forward a third assault, this time with tank support. The enemy quickly stampeded toward Am Aastert as accurate mortar fire rained down around the house, killing one of Turner’s men. When German infantry finally reached the farm, the mortar fire lifted, and they closed in on the eight surviving Americans.

From his position on the second floor, Turner heard a German voice order some of the troops to charge the building. Determined to keep them out, he rushed to the top of the stairs and fired into a mass of five Germans as they attempted to climb them. But his Garand only gave him two shots and then locked open with a ping as the empty en bloc clip ejected from the rifle. The survivors pushed the bodies of the two dead aside and continued climbing the stairs toward Turner with his now-empty rifle. Out of ammunition, the 24-year-old staff sergeant reached for the closest object that could be used as a weapon: a nearby oil lamp. Turner hurled the lamp down the stairs at his antagonists, and when it shattered it engulfed them in flames. They immediately fled the building on fire, but then a second wave of attackers rushed in.

Turner tossed a grenade down the stairs toward them and dashed into another room to shelter himself from the explosion. After the blast, Germans stormed into the hallway of the second floor and Turner met them in the doorway where he bayoneted two of them before they could raise their weapons. Turner then grabbed an MP40 from one of the dead Germans and used it as he fought from room to room. Although five of his men had been wounded, he refused to surrender and led the remaining two unwounded soldiers as they mopped up what was left of the German assault force.

When they emerged from the house, they found dazed and wounded Germans anxious to surrender—25 in all. The bodies of 11 German dead littered the farm—most killed by Turner himself. His exceptional actions ultimately resulted in Turner being awarded the Medal of Honor on June 28, 1945, but he never wore it or knew he had received it. One month to the day after his heroic actions at Am Aastert, Turner was killed in action.

By the end of January, the Bulge salient had been reduced, and American lines returned to where they had been before the Germans launched their offensive. It was the largest battle that the U.S. Army fought during the Second World War, and the cost was enormous, with 19,000 killed in action and almost 50,000 wounded. The German casualties were even worse: 91,000 killed, wounded and missing. But for all the enormity of it, the Bulge was very much a rifleman’s battle where soldiers such as Joe Cicchinelli and Day Turner marked the difference between defeat and victory.