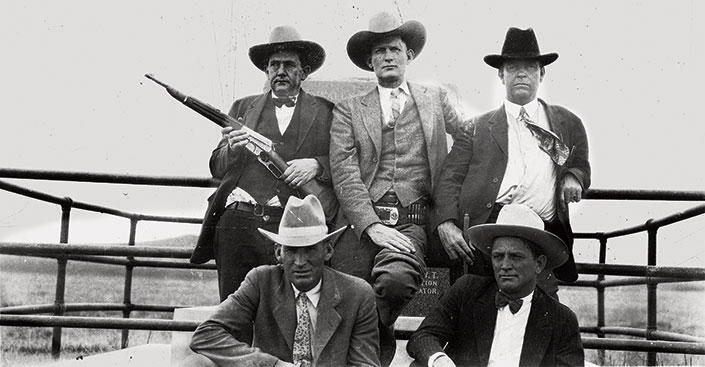

Ranger Frank Hamer along the Rio Grande on Bugler in the early days of his career.

The early years of the 20th century were a time of transition in the Southwest. This was especially true for law enforcement. Men who had started their careers riding horseback in pursuit of rustlers and bandits soon were called upon to deal with fast cars, Tommy guns and gangsters. Some of the lawmen couldn’t make the change while others who did became legends. One of those was Texas Ranger Capt. Frank Hamer.

Hamer was born on March 17, 1884, in Wilson County, Texas, down below San Antonio. While still a child, his family moved to San Saba County, in the Texas hill country, where his father ran a blacksmith shop. Hamer grew up helping his father in the shop, but the lure of the cowboy life soon took hold of him. Fully grown, Frank Hamer stood 6-feet, 3-inches tall and weighed more than 200 pounds.

By the early 1900s Hamer was working on ranches along the Pecos River in far western Texas. On several occasions he was instrumental in catching some of the rustlers who plagued the area. He was so successful that one of the western Texas sheriffs sponsored him for a place in the Texas Rangers. Frank Hamer enlisted in the Ranger service on April 21, 1906, joining Company C, commanded by the cool and professional Capt. John H. Rogers.

As a private in Co. C, Hamer worked the country along the Rio Grande from horseback. In those days, a Ranger company traveled around its assigned area, usually hundreds of square miles, just as they had done in the 1800s. They investigated reports of cattle rustling, smuggling from south of the border, and were continually on the lookout for wanted outlaws. It was still very much a frontier undertaking.

Back in those days, being a Texas Ranger was not the glorious job to which it has come to be regarded. Rangers generally camped out, could be sent anywhere in the state, were discouraged from being married and having a family, and they did it all for $30 to $50 per month, assuming the state treasury wasn’t broke. Enlistments were generally for two-year periods, and Rangers often decided not to re-enlist due to better job offers in other branches of law enforcement.

Although Hamer carried a Texas Ranger commission from 1906 until 1933, there are a number of periods during which he had resigned for better pay. During those times, he served as the city marshal of Navasota, Texas, as a special officer for the city of Houston, Texas, and as a federal Prohibition officer. Another factor in this job skipping was that Rangers served under the direct control of the state governor. And, especially during the early 1900s, governors used Ranger commissions as political plums. In certain administrations, corruption was rampant. In fact, Hamer and the entire Ranger force resigned in 1933 when Miriam “Ma” Ferguson took office.

In spite of these breaks in service, Hamer was a Ranger captain by the early 1920s. He had been involved in more than 50 gun battles and had been wounded a number of times. Throughout his lifetime, he was a private man. He would not discuss his gunfights and adamantly refused to say how many men he had killed. Legend takes over when a man like Hamer won’t talk, and the claim was often made that he had killed more than 40 men and one woman. I once told his son, Frank Hamer, Jr., that I thought the actual number was probably less than a dozen, and he told me I was right.

For a man to have survived this much gun smoke, he had to be good with a firearm, and Hamer was certainly that. In a time when most men shot well, he was known as an expert. He practiced long-range handgunning because he said a man didn’t know when he might have to shoot at a distance and not have a rifle handy. He was an avid hunter and known for his ability with a rifle. In fact, given a choice, Hamer preferred to do his fighting with a rifle.

Throughout his lengthy career, his favorite handgun was a single-action Colt .45 that he called “Old Lucky.” It’s unknown when he first acquired the gun, but it is described as a C-engraved, 4 3/4-inch-barreled, blued revolver. Like many lawmen of his era, Hamer adorned Old Lucky with carved pearl stocks, Gen. Patton’s injudicious remark notwithstanding. Hamer once told an interviewer that he rarely shot from the hip, preferring instead to bring the gun to eye level and use the sights. He didn’t think much of any officer who sprayed the countryside with lead when one good shot would do the trick.

But Hamer was also a believer in carrying a backup gun when the situation warranted it. One handgun that was a favorite of his was the Smith & Wesson 1st Model Hand Ejector (mfg. 1908-1915), which has come to be called the Triple Lock, in .44 Spl. Being a southpaw, Hamer carried Old Lucky on his left hip and often strapped the Triple Lock on his right hip, or in a shoulder holster.

Another favorite backup gun, as will be seen, was the Colt Government Model in .38 Super (introduced in 1929). Like many of his contemporaries, Hamer didn’t completely trust autoloading pistols. But he chose the .38 Super because of its ability to penetrate car bodies and the early “bulletproof” vests that some gangsters used.

Early photos of Capt. Hamer show him armed with a Winchester Model 1894 carbine, probably in .30-30 Win., and also a Savage Model 1899. Hamer likely was experimenting with various rifles to try to find the one that best suited him.

In about 1920, he found that gun in the Remington Model 8 autoloading rifle, manufactured from 1906 to 1936. The Remington Model 8 was chambered for the .25 Rem., .30 Rem., .32 Rem., and .35 Rem. cartridges. A John Browning design, the recoil-operated rifle featured a full-length steel sleeve that covered the entire barrel.

Hamer’s first Model 8 was in .25 Rem., and he used it during most of his Ranger career. The Ranger’s prowess with the rifle, however, soon came to the attention of Remington, and it presented him with a factory-engraved Model 8 in .30 Rem., which he prized. Of one gunfight down on the Rio Grande, a fellow officer once said that, when Hamer got his Model 8 into action, it sounded like a machine gun going off.

One of the best examples of Hamer’s ability to deal with a deadly encounter was a gunfight that occurred Oct. 1, 1916, in the western Texas town of Sweetwater. Although the fight was not connected to law enforcement, it is a good example of the man’s coolness under fire.

For some time, western Texas had been in the throes of a feud between the Johnson and Sims families. Hamer, who had recently married W.A. Johnson’s daughter, Gladys, was serving as a bodyguard for Johnson during a series of trials relating to some killings. Another former Ranger, Gee McMeans, was a son-in-law on the Sims side of the dispute.

When court proceedings were continued in Baird, Texas, Hamer started the drive back to his home in Snyder. In the car with him were his wife, Gladys, brother Harrison Hamer, and Gladys’ brother, Emmett Johnson. The quartet drove into Sweetwater and stopped at a garage on the town square to have a flat tire fixed. Gladys stayed in the car, Harrison and Emmett went off to find a restroom, and Frank went in to the garage office.

While Frank Hamer was in the office, another car drove up, occupied by Gee McMeans and H.E. Phillips. McMeans and Hamer came face to face on the sidewalk as the latter exited the garage. Without further ado, McMeans pulled a Colt .45 semi-automatic pistol and shot Hamer in the left shoulder at close range. Hamer slapped at the big auto with his left hand and the gun went off again, hitting Hamer in the right thigh this time. With that, Hamer took the pistol away from his assailant and began beating McMeans about the head and shoulders.

While this was going on, H.E. Phillips was sneaking up on Hamer with a shotgun in his hands. Seeing this, Gladys Hamer began shooting at Phillips with her Colt Pocket Auto. When Mrs. Hamer ran out of ammunition, Phillips closed for the kill. However, his shotgun blast, fired at close range, missed Hamer entirely. It merely tore off most of Hamer’s hat brim. And Hamer, stunned, went to the ground.

McMeans and Phillips, seeing that their plan hadn’t worked quite like it was supposed to, beat a hasty retreat back to their car. About this time, Hamer jerked his .44 Triple Lock and went after them. Seeing McMeans pull another shotgun from the car, with one shot Hamer hit him in the chest and killed him. Phillips, shotgun in hand, took off down the sidewalk, looking for a climate that had a little less lead in it.

At this point, Harrison Hamer showed up, rifle in hand, and took aim at the fleeing Phillips. Frank pushed the gun barrel up as the rifle went off and told Harrison he didn’t want Phillips shot in the back. At that point, the fight was finally over. Hamer had been shot twice, had killed McMeans and stopped his brother from shooting Phillips in the back. What is amazing is that the Nolan County grand jury was in session and had watched the whole fight from an upstairs window. While Hamer was being doctored, the grand jury met, heard his testimony, and “No Billed” him on the spot, declaring it self-defense.

By the 1930s, there was no deadlier gang operating than Clyde Barrow, Bonnie Parker and their associates. Across the country, they pulled numerous robberies and escaped several shootouts with law enforcement agencies. Not quite as famous as John Dillinger, Bonnie and Clyde were still a high priority for lawmen.

On Jan. 16, 1934, the clamor to stop Bonnie and Clyde heightened when they pulled a daytime raid on the Eastham prison farm to help Raymond Hamilton and three other convicts escape. A prison guard was killed during the attack.

Less than a month later, the director of the Texas prison system contacted Hamer and asked him to bring the pair to justice. Hamer, who had quit the Rangers due to gubernatorial politics, was commissioned as a Texas highway patrolman so that he would have legal authority to make an arrest. He chose another ex-Ranger, B.M. “Mannie” Gault, as his partner. The pair hooked up with two Dallas County deputies, Bob Alcorn and Ted Hinton, who knew Bonnie and Clyde personally. One of the greatest manhunts in the Southwest was on.

In a short while it was learned that the robbers frequented an area of northwest Louisiana, which was the home of one of their associates, Henry Methvin, who was traveling with them full time, but his parents farmed near the town of Gibsland in Bienville Parish. The four Texans quickly joined forces with the Bienville Parish sheriff, Henderson Jordan, and his deputy, Prentis Oakley. Also involved in this phase of the pursuit was New Orleans FBI agent L.A. Kindell.

During his lifetime, Hamer had very little to say about the Bonnie and Clyde investigation. And, unfortunately, after his death some of his biographers made it sound as though Hamer was leader of the investigation, rarely mentioning the six other lawmen involved. It should be noted that the four Texas officers had no legal authority in Louisiana, and it’s a good bet that Sheriff Henderson Jordan was the actual team leader. However, it appears that all of the officers got along well and that each contributed to the investigation.

A plan was soon hatched, probably by Sheriff Jordan, with the Methvin family to lure their son away from Bonnie and Clyde and set the pair up for an arrest. In exchange for this help, Hamer would get the Texas governor to issue a pardon to Methvin for the crimes that he had committed in Texas. The officers felt that the arrest should be made in an isolated area due to the probability that Barrow and Parker would elect to resist and shoot it out.

Shortly before May 23, 1934, Methvin’s parents lured Henry away from his outlaw friends. They knew that Bonnie and Clyde would come back to the area of the Methvin farm to try to hook back up with Henry. With that in mind, the officers selected an ambush site on the Gibsland-Sailes road not far from the Methvin farm. They had Henry’s father park his truck on the side of the road and take off one of the tires, believing that this would cause the outlaw couple to stop and check on him.

Across the road, behind some brush, were Ted Hinton and Bob Alcorn, Henderson Jordan and Prentis Oakley, and Hamer and Gault. At least one man in the group, Hinton, had a BAR. Gault was carrying Hamer’s Model 8 Remington, in .25 Rem., while Hamer was armed with his Model 8, in .30 Rem., Old Lucky and a Colt .38 Super.

On the morning of the 23rd, the officers were about to call off their ambush when Barrow and Parker drove up to the scene. Sheriff Jordan and Capt. Hamer both called on them to surrender, but Clyde, who was driving, put his car in gear and attempted to drive off. Bonnie and Clyde died in a hail of bullets.

Years ago, I knew two old Texas Rangers, Dan Westbrook and Lee Trimble, who had worked with Hamer. On separate occasions they both told me the same story. They said that when the Barrow car started to pull away, Hamer fired two quick shots with his Model 8 and then sat down and lit a Camel. Autopsy photos clearly show two head shots on the pair. While there is no way to document this tale, it is certainly within Hamer’s ability to have made those shots.

In the wake of the ambush, Hamer and Gault were heralded as heroes in the state of Texas. Hamer refused all interviews and would not even attend a banquet set up to honor the officers; instead, he returned to his family and avoided the spotlight. The next year, the Texas Rangers became part of the Texas Dept. of Public Safety in an attempt to remove them from the chaos of political payoffs. Unfortunately, the new Texas governor, James Allred, disliked Hamer and would not restore him to his rightful place in the organization that he had served so well.

Above the other lawmen of his time, Frank Hamer had successfully made the transition from the days of boots and horseback patrol to suits and Ford automobiles. He was as skilled at conducting criminal investigations as he was at gunfighting. For the rest of his working years, Hamer was part owner of a lucrative private investigation and security firm. He passed away on July 10, 1955. To the very end, however, he was known as a Texas Ranger, a man at arms, who helped bring the lawless frontier to a close.