Emir Faisal gave this Short, Magazine Lee-Enfield, Mk III (below), to T.E. Lawrence after it had been captured by the Turks at Gallipoli. It was engraved with “Part of our booty in the battles for the Dardanelles” before being presented to Faisal by Turkish leader Enver Pasha. Lawrence subsequently presented it to King George V. Lawrence who also had a penchant for Colt semi-automatics.

If you have ever seen David Lean’s majestic film “Lawrence of Arabia,” you probably remember the scene (or the movie poster) that shows Lawrence leading an attacking swarm of Arab rebels. His piercing blue eyes are filled with hate and bloodlust, while he carefully aims his revolver, a .455-cal. Webley Mk VI, at the enemy.

It is a riveting image that captures the popular essence of “Lawrence”—except that it is not Lawrence, it is actor Peter O’Toole. For many, that image is more readily recognizable as “Lawrence” than the man himself. But just as O’Toole doesn’t resemble Lawrence, the Webley is not the pistol that “Aurens” carried.

Let’s go back to July 1917 in what would become today’s Jordan, and take a look at what arms Lawrence really carried.

The Bedouin raiders had been in the field for nearly two months and were nearing their target: the port city of Aqaba. Capturing it would permit the Arab Revolt to move north to act as flank security for General Edmund Allenby’s army as he moved forward into Palestine. The Arabs’ British advisor was Thomas Edward Lawrence, soon to be known as “Lawrence of Arabia.” He was the only foreigner on this mission, and knew the move would put the Arabs in position to capture Damascus, the final objective of the revolt.

Following a route designed to deceive their Ottoman-Turkish enemies, the raiders reached Aba el Lissan on July 2, 1917, where they found a Turkish battalion blocking their way forward. The Turks were poorly positioned and camped in a valley near a well; they had just arrived in the area and appeared to be inexperienced based on their lack of security. Either that or maybe they felt safe in their own territory. Bedouin raiders would never attack a 600-man Turkish infantry unit—or would they?

Led by Auda Abu Tayi, one of the fiercest raiders of the Howeitat tribe, 550 Arabs moved into position above the enemy before dawn, occupying the high ground that surrounded the valley. As the sun rose, they began to shoot down upon the Turks. Often armed with antiquated .577/450 Martini-Henry, Lebel and Berthier rifles (both chambered in 8x50 mm R), they fired and fired again. Through the day, the air and ground on which they lay grew hot. Their rifle barrels, hotter still, blistered their hands, and many suffered from sunstroke, requiring that they be withdrawn from the line and placed in the shade to recover.

The Turks responded with ineffective rifle and howitzer fire. With the sun in their eyes, their sights couldn’t find targets and the cannon shells flew over the hills, exploding in the void beyond and hurting no one.

In the afternoon, Lawrence was also overcome by the heat and lay down in the shade trying to drink water from a small hollow in the hill. Auda found and challenged him, saying, “All talk and no work!” Lawrence cheekily answered that Auda’s men “shoot a lot and hit little,” prompting an enraged Auda to respond “Get your camel if you want to see an old man’s work!” Then Auda rallied his men and charged down the hill directly into the midst of the Turks.

Lawrence jumped onto his camel to follow and plunged down the hill with the howling fighters. The first indication that something was wrong was when Lawrence’s camel went tumbling heels over head down the long slope of the hill. He flew over the animal’s head and hit the ground hard, knocking himself unconscious. Seconds later he awoke to find himself in the middle of a gun battle. And, for some reason, he was reciting a poem while Turkish soldiers fired their German-supplied 1903 Mauser rifles at the screaming Bedouin rebels. The Arabs replied with their old rifles, most of which they had carried long before the British arrived. Swords flashed as Turkish officers tried to defend themselves in the onslaught. The Turk soldiers turned and ran or died fighting the raiders.

Lawrence thought he would be impaled on a Turkish bayonet as the fight swirled about him. He was defenseless, as he had lost his own gun when he was thrown from the camel. Then a shadow passed over him and Lawrence turned to see Auda Abu Tayi grinning at him from his mount. Auda’s cloak had been pierced by numerous bullets, his binocular destroyed and his sword scabbard bent where it was struck by a Turkish Mauser bullet. The battle was over.

Lawrence glanced across the field and saw many Turks dead or dying, while others were being pursued over the next ridge line. They too would soon fall. He would have preferred more prisoners, but there was little he could do at that point.

He looked at his camel. She had been a splendid beast, but he was even more dismayed when he discovered the wound that felled her was to the back of her head. In the fever of the charge, he had accidentally shot his own mount with his pistol—probably a .45-cal. Colt Model of 1911 or Government Model. Lawrence could mourn the loss only briefly, as there was work to be done. The captured Turkish arms were gathered up, and the prisoners of war were marched west, down the valley. Lawrence and his brothers in arms were on the way to Aqaba.

With the help of American journalist Lowell Thomas’s book and lantern show, Lawrence became famous. With President Woodrow Wilson’s authorization, Thomas had gone searching for a story that “would encourage the American people’s support” of the war. He first went to France where there was nothing inspirational. Then it was off to the Middle East, where he found Lawrence. Captivated by “the uncrowned King of Arabia,” Thomas created a show that was seen by more than 3 million people and wrote a book called With Lawrence In Arabia, launching Lawrence’s fame and making him one of the first media “superstars.” It must be said, however, that Thomas spent only a couple days with Lawrence, and much of his story is embellished.

Before his fame and stardom, Lawrence accomplished much in the Arab Revolt that helped Allenby to defeat the Turkish army in Palestine and Syria. Lawrence was a guerrilla advisor, one of a number of officers assigned to the “British Military Mission to the Hejaz” who worked with the army of Grand Sharif Hussein ibn Ali al-Hashimi, Emir of the Holy Cities of Medina and Mecca, Protector of the Hajj, and de facto ruler of the Hejaz. Hussein had long wanted to rid “Arabia” of its Ottoman oppressors, and got his opportunity when he saw he could ally himself with England against them.

In June 1916, Hussein launched his uprising. In the early months it was unclear if it would survive. Only with an influx of foreign aid in the form of arms, food and gold—along with a few British and French advisors and Royal Navy gunfire support—did the revolt begin to gain traction. Lawrence was the principal liaison and advisor to Emir Faisal, Hussein’s third son and the commander of the Arab Northern Army. Faisal and Lawrence worked well together. Lawrence’s linguistic skill and cultural acumen, along with a deep empathy for the Arab cause, brought him trust that was accorded to no other British officer in equal measure. And it was Lawrence’s counsel (as well as bags of gold sovereigns) that helped Faisal to build an alliance of tribes that would enable the advance north to Damascus. But Lawrence was an enigma—an amateur officer who eschewed British military traditions and discipline, and who loathed its seemingly mindless adherence to rules, regulations and conventions. Yet, when needed, he embraced its leadership, organization and resources to achieve the ends he desired.

Lawrence realized early that his small guerrilla army stood little chance of success defending fixed positions or attacking larger, better-equipped and -trained formations of the Ottoman-Turkish military. After Gallipoli, the Allies realized their enemy would not be a “pushover,” as many had thought.

He advocated that better arms should be given to the Arabs, but what they ended up with were leftovers—old British military surplus rifles, antiquated cannon and obsolete aircraft withdrawn from the front in France because they were too slow. It was only after Aqaba—and with Allenby’s blessings—that the Arabs began to get better arms in large quantities.

The advisors improvised, but none more so than Lawrence. He had already shown a technical aptitude and desire for modern arms and gear. As a young archaeologist in the region some years earlier he had purchased and become quite proficient with a Mauser C96 and a Colt Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless pistol.

Lowell Thomas would have us believe Lawrence carried “a Colt revolver of an early frontier model.” In his book, Thomas wrote that Lawrence told him a story about a thief who jumped him: “He sat on my stomach, pulled out my Colt, pressed it to my temple and pulled the trigger many times. But the safety-catch was on. The Turko-man was a primitive fellow and knew very little about revolver mechanisms. He threw the weapon away in disgust, and proceeded to pound my head with a rock. Since then I’ve always had a profound respect for a Colt and have never been without one.”

Lawrence with a revolver was perhaps Thomas’s romantic idea and an image that would be readily understood by Americans. After all, cowboys carried revolvers. But while Lawrence was romantic where political and social ideals were concerned, guns were another matter altogether. Furthermore, Colt revolvers did not have safety catches.

In actuality, Lawrence obtained two Colt pistols from America in September 1914 from Emily Rieder, who he knew from the nearby American Mission School. He sent one of the pistols to his brother Frank, who would later be killed leading his men on the Western Front. The letters he exchanged with his brother and father that discussed ammunition and takedown procedures make it clear that Lawrence carried a Colt .45 M1911 semi-automatic pistol. There is only one photograph known that depicts Lawrence with a pistol and, although the photo is grainy and the image small, it appears to show him in 1917 with a Colt semi-automatic. He also said he preferred the pistol because “only an expert could use a rifle” while mounted.

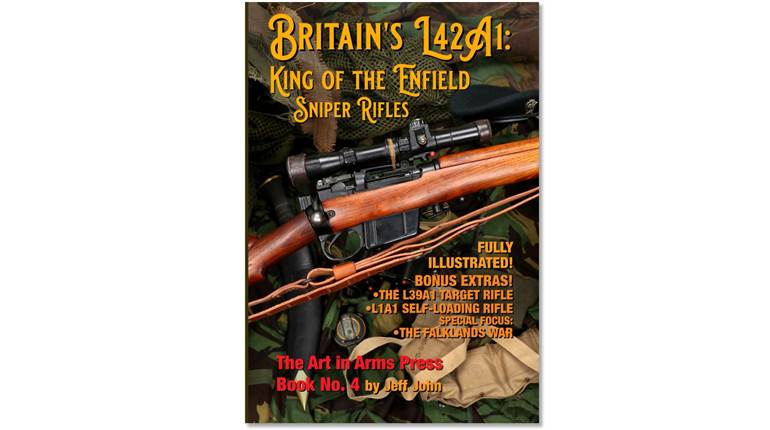

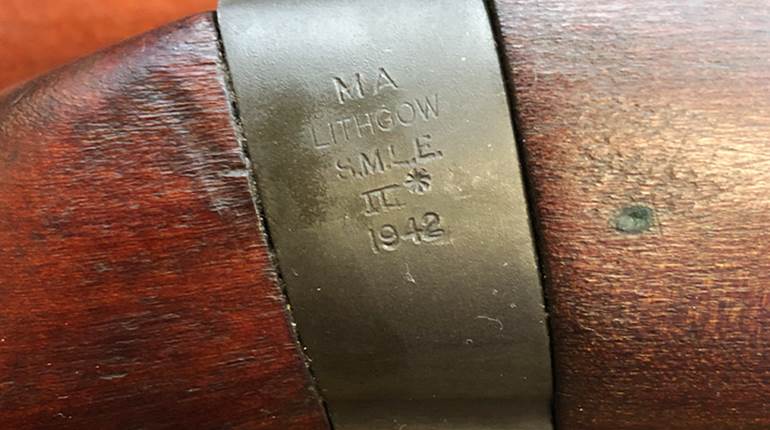

The pistol was not his only gun. Emir Faisal gave him a British .303-chambered Short, Magazine Lee-Enfield or “SMLE.” The successor to the longer and heavier “Long Lee” Lee-Enfield Rifle, the SMLE was the most famous British infantry rifle of the 20th century. Indeed, it was a venerable rifle, with Lee-Enfields serving the Empire in every one of its military confrontations from the Great War to the Suez Crisis of 1956/1957 and into the 1960s. Even after the No. 4 was replaced by the L1A1 Self-Loading Rifle (SLR), it could be found in variants such as the L42 sniper rifle, and was still in service with the Canadian Rangers as late as 2016.

Lawrence’s rifle had been captured from the British by the Turks at Gallipoli in 1915, and could be traced to the Essex Regiment. Ottoman leader Ismail Enver Pasha gave it to Faisal before the Arab Revolt began—perhaps as a warning to stay loyal to the regime. Faisal, in turn, gave the rifle to Lawrence in 1916, who kept it through the end of the war. It was engraved, and, when Lawrence presented it to King George V after the war, he explained that its inscription read “Part of our booty in the battles for the Dardanelles.” Another chilling reminder of the nature of war was left on its stock: five notches signifying the men Lawrence shot with the rifle until he sickened of keeping tally of the killings. The rifle can be seen in the Imperial War Museum in London.

But the SMLE was not his only long gun, and he carried different arms throughout the campaign. Lawrence was fascinated with another American design: the Lewis light machine gun. The Lewis was developed by Col. Isaac N. Lewis, and was based on an earlier gun by Sam Maclean. Lewis improved and lightened it for ease of use. Although it initially failed U.S. Ordnance Dept. tests, it was adopted by the Belgians and British prior to World War I. The British version was made by Birmingham Small Arms Co. in .303 British, under license from Armes Automatique Lewis SA in Belgium. The SMLE fired a 174-gr. bullet at 2440 f.p.s. (Mk VII cartridge) and had an effective range of 500 meters.

Lawrence carried the “Air Lewis” version of the gun that he apparently appropriated from one of the Royal Flying Corps’ obsolete B.E.2c fighter aircraft and fitted with a wood stock. The gun had no cooling jacket, lightening it significantly. The Lewis was also chambered in .303, and fired around 550-600 rounds per minute. He carried it in a special leather scabbard tied to his camel saddle, and favored it over his other arms. He thought that all of his raiders should be so equipped, making them a camel-mounted, mobile machine gun corps. Limited supply and the lack of the requisite training necessary kept that idea from fruition.

Lawrence’s guns were not limited to his personal pistol, rifle or machine gun. He combined those with other means to accomplish the mission. After all, having good arms means nothing if your tactics are bad. Lawrence summed up his ideas in a number of articles, but is best known for his autobiography, Seven Pillars Of Wisdom. In it he writes, “The few active rebels must have the qualities of speed and endurance, ubiquity and independence of arteries of supply. They must have the technical equipment to destroy or paralyze the enemy’s organized communications.”

He did not invent guerrilla warfare, nor did he need to teach it to the Bedouins; they were well-versed in “hit-and-run” operations long before the British came along. What he did was to take advantage of their skills and provide them the means to harass the Turks and destroy their supply lines without being destroyed themselves. He also provided the gold that permitted Hussein and his sons to unite the disparate tribes into a formidable force to fight a common enemy. They would never win the war alone, but they did serve as an important auxiliary force that distracted, diverted and often fixed the Turks to one position, preventing their deployment to locations where they were needed more.

With dynamite, gun cotton and gelignite, the British advisors taught the Arabs how to destroy railway lines using the same techniques Boer Commandos had used against the British in South Africa. In fact, the first demolitions used the same ignition system: a cut-down Martini-Henry rifle action. Placed under a railroad track, a cartridge ignited the explosives when the trigger was actuated by a passing train.

Beyond ideas and explosives, another innovation was exploited by Lawrence. It was what we today call the “technical”—a civilian vehicle weaponized for military purposes. One was a simple Talbot truck that was used as a mobile gun platform. Organized as the Royal Field Artillery (RFA) 10-pounder Motor Section, the unit consisted of two trucks (plus others to offer support) that each carried a Breech Loading 10-pounder Mountain Gun. An antiquated gun weighing 900 lbs., it was chambered for a 2.5" shell and had an effective range of 3,400 meters. The relatively short range was a problem, as the Turks they faced used German or Austrian guns that had a longer reach. The guns were normally offloaded and fired from the ground, but they could also be fired directly off the rear beds of the trucks, making the Talbots one of the first mobile gun platforms. The guns were first employed in attacks on Tel al Shahm and Wadi Rutm along the Hejaz Railway, in early 1918, and most successfully in the August 1918 battles at Mudowwara, where the section supported the Imperial Camel Corps’ successful attack that captured the large fortress.

Probably the most unique “technical” used in the campaign was the 1914 Admiralty Pattern Armoured Car. Based on the Rolls-Royce 40/50 “Alpine Eagle” model (later known as the “Silver Ghost”), it was powered by a six-cylinder 7,428-c.c. engine producing about 75 b.h.p. with a four-speed transmission. Each had two tons of 3/8" steel armor, along with extra spring leaves and dual rear-wheel assemblies to carry the weight. The cars had a rotating turret with a Maxim or Vickers .303 machine gun. The gun could be quickly dismounted for ground use on a tripod when necessary. The Vickers/Maxim was fed with a 250-round belt and had a sustained rate of fire of 450 to 500 rounds per minute. It was accurate to around 2,200 meters, although it was often used at longer ranges. Even with all the extra weight, the armored version could hit 60 miles per hour. But, at around 4 miles per gallon, gas mileage wasn’t their best feature.

The cars were used primarily to attack strongpoints—forts and rail stations—as well as to provide overwatch when demolitions teams set charges on rail lines and bridges. Unarmed Rolls-Royces, called “tenders,” accompanied the armored cars and carried personnel, fuel, water and the demolition materials needed to support each mission, as the armored cars had little room to carry supplies. It was the tenders that were used for long-range reconnaissance; four days’ worth of supplies meant the raiders could reach areas with a speed not otherwise possible. Moreover, the Rolls-Royces rarely had breakdowns, and, when they did, it was usually because the vehicles’ suspensions were subjected to extremes far beyond factory expectations during cross-country driving.

The Rolls-Royces, and even some Ford Model T cars, were very effective in the campaign and inspired the use of armed raider jeeps in World War II by units such as the Long Range Desert group and the Special Air Service.

Of course, Lawrence—ever the odd man out—often used an older 1909 Rolls-Royce tender he had himself appropriated from a British diplomat in Cairo. He was photographed in the car, nicknamed “Blue Mist,” in Damascus at the end of the war. That image has survived as one of the most iconic of Lawrence.

While the Arab Revolt did not single-handedly win the war in the Middle East, it did assist Allenby to win his campaign. Lawrence had a talent for employing the Great War’s new technologies: semi-automatic pistols, airplanes, electric detonators, machine guns and motorcars. The equipment used by T.E. Lawrence and his colleagues against the Turks was innovative, as was his untraditional approach to the employment of intelligence, aerial reconnaissance and mobile gun platforms. His methodologies were game-changers and would heavily influence what would later be known as special operations in the British military, not to mention guerrilla leaders such as Mao Zedong and Võ Nguyên Giáp.

This article is adapted from the book Masters Of Mayhem: Lawrence Of Arabia And The British Military Mission To The Hejaz—The Seeds Of British Special Operations by James Stejskal. Printed by Casemate Publishers, it is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble booksellers.