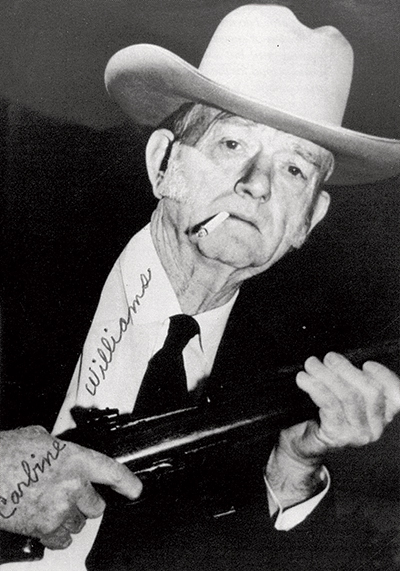

The M1 carbine of World War II, such as this example made by Winchester, gained great favor and fame among American G.I.s and was the result of several creative minds, including that of David Marshall Williams. Williams is shown holding an M1 Carbine in a “publicity” photo signed “Carbine Williams.”

There are many stories involving iconic figures in the history of the United States that are known by generations of Americans but which, to be charitable, may be less than 100 percent factual. For example, we’ve all heard that George Washington chopped down a cherry tree (and didn’t lie about it), Betsy Ross was responsible for sewing the first American flag and Al Gore invented the Internet. However, these stories have all been proven to be more apocryphal than factual or, in the current vernacular, “urban legends.” Along these same lines, one enduring story regarding firearms is that of David Marshall Williams, a.k.a. “Carbine” Williams, who is widely credited with “inventing” the M1 carbine of World War II fame. According to popular folklore, reinforced by a 1950s Hollywood movie, Williams invented the carbine using scrap metal and crude machinery while serving a stint in a Southern prison in the 1920s.

Like many “urban legends,” this one contains at least a grain of truth. Born on Nov. 13, 1900, in Godwin, N.C., David Marshall Williams, known as “Marsh” to his friends and family, dropped out of school in the eighth grade. He worked for a brief period on the family farm but eventually sought a job at a blacksmith shop where he displayed an affinity for metalworking and machinery. Williams joined the U.S. Navy but was discharged when it was discovered that he misrepresented his age and was actually too young to serve. After leaving the Navy, he spent one semester at Blackstone Military Academy in Virginia before being expelled. Williams returned home to North Carolina where he married and later had one child.

Williams was “augmenting his income” by operating an illegal still and turning out moonshine when, in 1921, the bootlegging operation was raided by law enforcement officers and, in the course of the raid, a deputy sheriff, Alfred J. Pate, was shot and killed. David Williams was charged with first-degree murder, but the trial ended in a hung jury. Rather than risk a second trial, Williams chose to plead guilty to a lesser charge of second-degree murder and was sentenced to 20 to 30 years at the Caledonia State Prison Farm in Halifax County, N.C. While serving his sentence, Williams spent hours sketching diagrams for various firearm mechanisms. As he gained the confidence of the prison superintendent, H.T. Peoples, Williams was given access to the prison workshop where he spent his spare time repairing and maintaining the equipment and working on some of his firearm ideas. Friends and relatives began a campaign to have the governor commute his sentence. These efforts proved to be successful as Williams was granted parole in 1929 and totally released from prison in 1931.

He returned home and continued refining his ideas. Two of the more significant inventions hatched by Williams while in prison were the “floating chamber” and the short-stroke gas piston. The floating chamber (sometimes called a “moveable chamber”) device permitted a .22 LR cartridge to generate sufficient force to cycle a large caliber semi-automatic or full-automatic mechanism.

A few years later, Williams felt that his plans were developed sufficiently for presentation to the War Department. Ordnance officials were impressed with Williams’ floating chamber design as it enabled arms ranging from the .45 automatic pistol to heavy machine guns to fire .22-cal. rimfire ammunition for training purposes.

Williams And Winchester

Williams’ efforts and obvious talents did not go unnoticed, and he soon caught the attention of one of the nation’s largest firearm manufacturing firms, Winchester Repeating Arms Co. The personal files of Edwin Pugsley, the long-serving chief executive of Winchester, contain quite a bit of information regarding David M. Williams’ association with the company. Among the earliest references to Williams found in Edwin Pugsley’s files was the following: “My attention was first directed to Williams by General Hatcher of the Ordnance Department in 1938. Hatcher told me that in his opinion Williams showed the greatest native ability of anyone he knew of. [Hatcher] was particularly impressed by the changes [Williams] had made to make the heavy Browning machine gun operate as a training weapon using .22 Long Rifle cartridges and the moveable chamber principle.”

General Hatcher apparently arranged a meeting in Washington, D.C., with the inventor and Winchester’s Edwin Pugsley. As Pugsley subsequently wrote: “From the meeting with Williams, and the general investigating I did in Washington, I also was impressed with him and subsequently asked him to bring us his .22 automatic machine gun in order that we might look at it. He did this and the workmanship was outstanding.”

David M. Williams’ talents and ability were obvious, and Winchester was interested in possibly employing him in some capacity. As related by Pugsley, however, the subsequent negotiations did not go smoothly. There was apparent misapprehension on both sides as Williams showed some reluctance to the idea of working for the corporation. On the other hand, Pugsley was not sure that Williams had the temperament to fit into the firm’s corporate structure. This was revealed in a candid memo written by Pugsley to the parent company’s “Operating Committee” dated April 21, 1939:

“With respect to the services of D.M. Williams, I think the matter largely will be determined upon the decision of the New Haven organization as to whether or not it will be possible to live with Mr. Williams. He is a peculiar individual, I think he has ability, but whether or not he can be worked into an organization is a question to be determined.”

Despite these misgivings, Pugsley recognized Williams could potentially be a valuable asset to Winchester and he continued efforts to come to terms with the inventor. This was related in a subsequent report by Pugsley: “We … entered into negotiations with Williams during which I learned one of his outstanding characteristics; namely his slowness in committing himself on anything. I met him in Washington several times and he came to the plant at least twice before he was willing to accept the idea of being an employee. He entered the employ of the company on July 1, 1939 on a one year contract.”

One of the first tasks assigned to Williams was a project to refine a .30-cal. semi-automatic rifle designed by Ed Browning (John M. Browning’s brother) designated by the company as the “Caliber .30 M2 Browning Military Rifle.” Browning had been working on the rifle at the time of his death, but the mechanism had not been perfected and the rifle would not function satisfactorily. As reported by Pugsley: “Williams swung into the … Browning Military rifle (project) and we finally determined that the cause of our difficulty was the uncertainty of action due to the unique piston device which Browning was using, consisting of a doughnut shaped piston sliding over the outside of the barrel which was given the initial blow by the gas.

“At a conference one morning Williams informed me that he believed he could make the gun work, but if he did he would have to employ a device on which he owned the patents and hence if we used this device we would have to settle with him. He then described his proposal to put the short stroke piston on this gun and I told him to proceed.”

Williams’ modification of the Browning rifle to utilize the short-stroke gas piston proved to be successful. When the U.S. Marine Corps announced trials to be held in San Diego for the possible adoption of a semi-automatic rifle, Winchester submitted the improved “M2” rifle to be tested along with the M1 Garand and a recoil-operated rifle developed by Melvin M. Johnson, Jr. While the Winchester rifle did not fare well and was eliminated from consideration because of design deficiencies unrelated to its gas system, Pugsley remarked that “This model showed the very decided possibilities of the short stroke piston.”

Even though the “M2” rifle did not acquit itself well during the testing in San Diego, Winchester was encouraged enough by the improvements made by Williams to continue development. Although the M1 Garand had been adopted as the standard U.S. Army service rifle in 1936, nagging functioning problems resulted in much criticism of the design and Winchester harbored hopes that its semi-automatic rifle might be improved sufficiently to be considered as a replacement for the widely denounced (at the time) Garand rifle. As events transpired, most of the complaints against the M1 rifle were eventually resolved and the Garand was firmly ensconced as the standard U.S. service rifle. Even though the “M2” rifle did not succeed in Winchester’s quest to replace the M1 Garand, Williams’ efforts in improving the rifle by means of his proprietary short-stroke gas piston were soon to pay dividends to the company.

The M1 Carbine

During this same period, the U.S. Ordnance Department announced plans for the procurement of a “light rifle” (weighing not more that 5 lbs.) that was intended to replace the .45 ACP M1911A1 pistol and the Thompson submachine gun. Firms and individual inventors were solicited to submit designs for the proposed new arm. Initially, Winchester was uninterested in entering the design competition for several reasons, including the fact the firm was now in the process of manufacturing the M1 Garand rifle under government contract. Ordnance officer Col. Rene Studler had been impressed by the improved “M2” rifle, however, and personally lobbied Winchester to submit a “light rifle” design based on it. As stated by Pugsley: “Studler was taken by the way the big gun (M2) worked, and also the fact that it only weighed seven pounds, and demanded that Winchester build a carbine. He intimated that the models they had tested to date were unsatisfactory and they were in great need of such a gun.”

Winchester relented and agreed to proceed with a design but since the company had entered the “light rifle” competition late in the game, it had only 13 days to come up with a satisfactory entry before expiration of the mandated time period. In order to meet this abbreviated time frame, Winchester fabricated a design that was little more than a scaled-down “M2” rifle incorporating the Williams-designed short stroke gas piston. Even so, numerous changes were required and the Winchester engineering team went to work, literally around the clock, in order to fabricate a working prototype in time to satisfy the government’s requirements. Unfortunately the misgivings the company initially harbored regarding Williams’ ability to work within an organized corporate structure began to be realized.

As stated by Pugsley: “Williams was extremely upset by the Winchester organization proceeding with this gun in spite of him, and he warned me several times that he would not be responsible for anything concerning it, that he did not wish his name associated with it in any way, and notified me that I was doing this entirely on my own responsibility. I accepted this situation and we proceeded to get the gun to operate without any help whatsoever from Williams. We did, however, practically copy the .30 M2 seven pound Winchester Military Model which Williams had previously worked out, using the short stroke piston, general arrangement of the bolt, receiver, and slide as demonstrated in that gun.”

Obviously, Williams was unhappy with the manner in which Winchester chose to proceed with the development of the new gun, and he reportedly even threatened the life of a key company employee. This was related by Pugsley as follows: “When I returned from Washington to find nothing done, I was urged to go immediately to the Experimental Shop as Williams was supposed to have threatened to shoot Humeston because of his having gone ahead on some cuts without asking Williams. I found Williams under the impression that the company was going to try to steal the short stroke invention. I assured him there was no such thought and told him that instead of shooting Humeston he (Williams) stood to gain if the gun worked. This quieted the situation but Williams still refused to have anything to do with the gun. We therefore again cut loose from him and he worked on another model of the carbine which he finally finished in about December, 1941.”

Interestingly, despite his obvious irritation and dissatisfaction with the Winchester organization, the different model carbine that Williams had worked on after having been dismissed from the original “light rifle” project again demonstrated his true talents for firearm design. Although this design was completed too late for submission to the Ordnance Board, Pugsley stated, “The carbine he (Williams) produced was unquestionably an advance on the one that was accepted … .”

Despite the turmoil and hard feelings his presence at Winchester often engendered, the company was astute enough to realize that David Marshall Williams possessed a great deal of natural ability as a firearms designer and wished to salvage its relationship with him. To this end, Pugsley related the following: “When the gun was ready, I called Studler and asked him to come up to see it and he agreed to be up the next morning. I then went up to have a talk with Williams, told him Studler was coming and that we were going to show this gun to him; that I would be glad to have Williams demonstrate the gun if he would cooperate and demonstrate the rifle to the best interest of Winchester, but that unless he would agree to this I would not have him present and would demonstrate the gun myself. Williams agreed to cooperate and accordingly Williams, Humeston and I took the gun to Pine Swamp and Williams demonstrated it in a very satisfactory manner.”

While the rather crudely fabricated prototype was intended only to demonstrate the basic design premise, the Ordnance Department was impressed enough to encourage Winchester to develop an improved model for additional testing and evaluation. The company had until Sept. 15 to produce an example capable of standing up to the rigors of the grueling final trials. The Winchester team began preparations for fabrication of the improved model.

As stated by Pugsley, “The arrangement was that Williams would direct the design, and that Roemer would put it on paper in order to furnish dimensions fast enough for the Experimental Shop to carry on. Everybody agreed that this was satisfactory and I then had to leave for Washington where I stayed about three days. When I came back I was disgusted to find that very little had happened, that Williams had refused to cooperate and that little or no progress had been made. It was apparent that Williams could not pull the dimensions for the design of the gun out of his head as fast as the Experimental Shop could cut the steel and therefore it was necessary to make some other arrangement. There had been some beginnings made on the receiver and Williams told me a mistake had been made and he wanted to abandon what little had been done and have three men work all night to catch up to where he thought they should be. After looking over the situation, I decided that there was no reason for this and refused to let the men work all night. I therefore told Roemer and Humeston that we would disregard Williams and proceed to make the carbine following the general lines of the No. 1 gun, plus the .30 M2 seven pound gun, plus refinements necessary to have the carbine fall within the requirements set up by the Ordnance Department for this weapon. Roemer and Humeston then cut loose and Williams continued to sulk and to think about a design of his own. He repeatedly warned me that he would take no responsibility in this gun and that I would have to proceed entirely in accordance with my own ideas.”

The Winchester engineering and design team was successful in fabricating a specimen for the Ordnance Department trials. Eventually, the Winchester entry won out and on Oct. 1, 1941, the company was officially notified that their gun had been adopted. Production contracts for the “U.S. Carbine, Cal. .30 M1” were eventually granted to 10 firms, including Winchester. Winchester was the only one of the 10 prime contractors that had manufactured firearms before the war. The company produced more than 800,000 carbines (about 13½ percent of the total) by the time production ceased in 1945. The M1 carbine was manufactured in greater numbers than any other U.S. small arm of World War II.

After the war, Williams continued a tenuous working relationship with Winchester into the early 1950s, despite the obviously strained relationship. During this period, Winchester briefly engaged the services of Melvin M. Johnson, Jr., inventor of the Model of 1941 Johnson Rifle and Light Machine Gun. An amusing story involving Johnson and Williams was related in the book Johnson Rifles and Machine Guns: “The two rather headstrong and egotistical individuals (Williams and Johnson) soon became rivals and were, to say the least, not on the best of terms … . Undoubtedly Johnson and Williams had preconceived notions about each other, and the two soon clashed.

“Both men, although not at the same time, would visit the development shop at Winchester and proceed to lambaste the other. The draftsmen in the shop would stop their work and listen to the criticisms, often quite personal, that each man would cite against the other. The Winchester workmen would take bets on which man would emerge victorious when the expected fisticuffs finally ensued. However, likely to the regret of the draftsmen, there is no evidence that the two prima donnas ever ‘duked it out.’”

Williams eventually departed Winchester amidst hard feelings on both sides. It is reported that Williams repeated his earlier accusations that Winchester tried to steal his ideas and did not give him proper credit for his efforts. The management of Winchester, on the other hand, was probably not particularly unhappy to sever the relationship with Williams. While not specifically stated, the company had apparently previously attempted to “cover its bases” should Williams have instituted any sort of legal action against the company for the alleged “theft” of his short-stroke gas piston idea. This was revealed by Pugsley in a memorandum written on June 20, 1951, which, in part, stated: “After a great deal of searching in the United States Patent Office we found an old patent that disclosed Williams’ idea on the short stroke piston, which apparently had been overlooked by the Patent Office when they allowed his patent covering the construction proposed by Williams for the carbine. Since we had been granted a license by Williams we were bound not to contest the validity of this patent without terminating our License Agreement. We foresaw years of litigation and we felt such litigation would not be worthwhile in view of the pending emergency … . There is no question in my mind but that the basic patent owned by Williams covering the short stroke piston could be upset due to showing of the prior art; however, it would take considerable time and run to great expense.”

In other words, according to Edwin Pugsley, even Williams’ only substantive contribution to the design of the M1 carbine, the short-stroke gas piston, was not really his original idea. Pugsley concluded his memo with the following statement regarding David M. Williams’ tenure during the development of the M1 carbine: “During the building of both the experimental model and the final model that was tested, Williams went out of his way to insult and estrange practically every man he was supposed to work with, and from that standpoint was probably the most unpopular man in the section.”

Not long after his final departure from Winchester, Hollywood became aware of the Horatio Alger-like tale of the former convict who, while still incarcerated, invented (as the story goes) one of the most popular and prolific arms of the recently concluded World War. In 1952, the movie “Carbine Williams,” starring the legendary actor Jimmy Stewart, was released to generally favorable reviews. This obviously resulted in a great deal of publicity for Williams, and afterward he would routinely sign black-and-white glossy prints of himself with the moniker “Carbine Williams.” Williams did a bit of consultant work for some firearm manufacturing firms for a period of time before retiring and spending the rest of his days in North Carolina. David Marshall Williams passed away on Jan. 8, 1975 at the age 74.

As can be seen, the design that was to become the M1 carbine was very much a product of the entire Winchester organization. The short-stroke gas piston designed by David M. Williams was an integral part of the little rifle, but any claim that he “invented” the M1 carbine is without merit. This is not to denigrate Williams’ abilities in any way, as he was clearly a man with an unquestioned innate talent for firearm design. His inspiring life story of going from a convict to a noted arms designer in a few years is truly an American success story. It must also be remembered that there are “two sides to every story” regarding Williams’ stormy association with the Winchester organization. Edwin Pugsley considered Williams to be a talented and gifted arms designer but felt he was a major distraction to the smooth operation of Winchester in general, and the M1 carbine development program in particular. Williams, on the other hand, apparently felt that he was not given the deference and recognition he was due and believed that the company was trying to steal his ideas without credit or just compensation. Whether Pugsley was right or Williams was right or, perhaps, there was a bit of truth in both positions, Williams was undoubtedly a gifted individual who overcame a great deal of adversity. While he clearly didn’t “invent” the M1 carbine, his place in firearm history should not be slighted or forgotten. He was a most unusual and, in some ways, remarkable man.