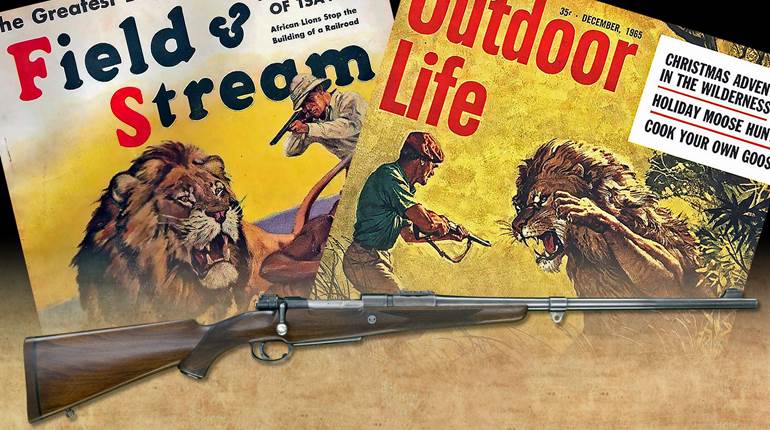

This is a story about a particular rifle that has truly stood the test of time over a period of half a century, accounting for many excellent trophies on numerous safaris in several different countries over that period of time. No, it’s not a custom masterpiece costing many thousands of dollars; it is an “off-the-shelf” Remington Model 721 in .30-’06 Sprg.

I will endeavor to relate here some of the highlights of the performance of this very ordinary, but, in my mind, unique rifle that was used on safari for a period of more than 50 years. To tell the entire story of all its successes would fill a book.

The first time I saw this rifle was at the customs desk in the Nairobi airport in 1953. It was one of the firearms to be used on a six-week safari booked by a Mexican client and his son who were part of a large, influential family by the name of Longoria hailing from the Laredo area just south of the border. The father, Chito, and his son, Chitito, hoped to collect between them the Big Five, plus a comprehensive bag of East African antelope.

Other guns they had shipped included two Winchester 12-ga. pump shotguns and two Remington pump-action .22s. The clients planned on hiring two double rifles in .470 Nitro Express from the outfitters, Ker & Downey Safaris, for the dangerous game—elephant, rhino and buffalo. While handling the guns when clearing customs, I noted that all the guns had seen considerable usage, but appeared to be in good condition. Someone had tried their hand at checkering the pistol grip and fore-end of the Model 721, and a shotgun-style recoil pad had been fitted. I noted with satisfaction that a good quality 4X Redfield scope had been mounted using sturdy Weaver-style mounts and rings.

To say that Remington’s Model 721 was plain is an understatement. It was very basic, with a stamped steel trigger guard integral with a fixed magazine cover plate; even the safety catch was a stamping. The trigger mechanism, which exhibited a crisp single-stage pull, was also made from stampings. The Model 721 had a tubular receiver, recessed bolt face, button-rifled barrel and the “three-rings-of-steel” breech design.

This was a simple production rifle that proved to be good value and utility for those hunters who wanted an accurate and reliable gun without paying a fortune for it. The Model 721 and the short-action version, called the Model 722, were introduced in 1948 and saw production through 1962, when Remington’s extremely popular Model 700, based on the Model 721’s proven design, took its place. During its time, I imagine many hunters and shooters discovered, as I did, that the Model 721 was one of the most accurate mass-produced centerfire rifles of its time, and in the early 1950s it sold for less than $90.

I was intrigued, as I had seen one of these Remington “economy” rifles in .30-’06 on a previous safari with Robert Ruark. Bob brought one on his first Horn of the Hunter safari, and in spite of my initial reservations, it had surprised me by performing very well. In fact Bob collected most of his plains game and a leopard with it. He continued to use it on all his subsequent safaris, and I have to say it was the one rifle with which he could shoot really well. It was very accurate with no feeding problems (I even tried chambering a cartridge with the rifle upside down with success) and a trigger pull that a very expensive custom rifle would be proud of. The only possible criticism I could make would be that it might be a little slower clearing a jam due to the fixed magazine cover plate. I wondered if the Longoria rifle I was examining would acquit itself as well.

We commenced hunting in the Tana River region of Kenya’s Northern Frontier District (NFD). We expected to collect desert antelope as the hunt progressed, but the emphasis was on elephant and possibly rhino. After sighting in the Model 721—it shot a very tight group—my impression gained from the rifle of the previous safari was being confirmed.

A couple of Hunter’s hartebeest, or “Hirola”, both one shot kills, were collected on the first day’s hunting from the stretch of barren featureless scrub bush that stretches from the Tana River to the Somali border where these most attractive antelope of the hartebeest family make their home. Two lesser kudu, one of the most beautiful of antelopes, were bagged the second day and, as the hunt for elephant progressed, a couple of good gerenuk were added to the bag. The Model 721 was proving to be extremely accurate and effective using 180-gra. Winchester Silvertips.

We followed a number of large bull elephant tracks whenever we came across them but, as is often encountered with elephant hunting, we were repeatedly disappointed by small or broken ivory. When we were finally able to locate a nice bull of about 80 pounds-per-tusk in thick bush, Chitito quickly dispatched it using a double .470 supplied by the safari company.

We moved camp from the Tana River area eastward to the great sand riverbeds, or luggas, that drain the floodwaters from the Mathews range during the rains to be absorbed and evaporated by the scorching sands of the Chalbi Desert. We again set about hunting for elephant and rhino at the same time, collecting various animals such as Grevy’s zebra, Burchell’s zebra, Beisa oryx and northern Grant’s gazelle with the Model 721.

One day while we were following a good elephant track, we disturbed a rhino. It blundered about not really knowing whether to charge us or get out of the way, but as it had a very acceptable horn, Chito took a shot, knocking him down with the first shot from the .470 and finishing him with his second barrel.

By then, we had only one more elephant to collect in the NFD before moving the safari to Tanganyika, a three-day drive. Cruising along one of the luggas one morning, we came across a huge elephant track. It was fresh, but heading toward the Mathews range, which was within the Northern National Park, the boundary somewhere in the not too far distance. We abandoned the Land Rover and followed as fast as the loose sand would allow, hoping to come upon the bull before he crossed back into the Park. We tracked as fast as we could, but in places where he had crossed rocky ground, tracking was slower. Before long, we were gratified to hear a branch break and realized we were close.

He was in some thick bush when we first caught sight of him, the tusks hidden by the foliage. Just then, he lifted his head and I caught a glimpse of a grand tusk--long and thick. Now we had to find out if he had a tusk on the other side. As we waited with bated breath, he moved and we could finally see the other one. It was shorter than the first one, but still well over a 100 lbs.

He was moving slowly toward the edge of the thick bush so we moved into position to be able to shoot as soon as he was clear. He came forward slowly and, as soon as his shoulder was visible, I whispered to Chito, “Take him!”

Chito fired and the elephant flinched. When Chito gave him the second barrel, he took off across the front of us. As I was not sure how far the Park boundary was, and five miles to a fleeing elephant is a short run, I was taking no chances and I brained him with the .416 Rigby. He was a grand old bull, huge in body, and when we delivered the trophies to the taxidermist in Nairobi his tusks weighed in at 125 lbs. and 112 lbs.

We set up camp in northwest Tanganyika after two full days traveling from Nairobi and immediately set about scouting the area. No other safaris had been in the vicinity for some time and our chances looked promising.

As we collected more trophies, we removed the head and cape and the carcasses were hauled into suitable trees as bait in areas where a leopard might be lurking. The smaller gazelle-sized animals and warthog were used whole while the larger animals, such as Coke’s hartebeest, topi and zebra, provided two or three baits. The Remington was kept busy.

During the next few days, a large eland bull, and an outstanding waterbuck were bagged with the .30-’06 and a good buffalo with the .470. One morning as we were routinely checking our leopard baits, one of the trackers on the back of the Land Rover drew my attention to something a long way off across an open plain. The binoculars revealed a fine male lion accompanied by two lionesses. They were walking very slowly toward a patch of bush to our left front. We decided to abandon the vehicle and go on foot toward the bush where they were heading, hoping to intercept them as they approached it.

All went well as we hurried toward the bush, hidden from the lions. We reached it only to find they were nowhere to be seen. Had they somehow sensed our presence and moved off? Surely not. The wind, what little there was, appeared to be in our favor.

I kept scanning the area where we had last seen them with the binoculars and finally spotted a little black blur moving in the short grass. I climbed a low tree and there they were about 300 yds. off lying absolutely flat in the grass. What I had seen was the tip of a swishing lion’s tail.

Finally, after what seemed like ages, one of the lionesses stood up, yawned and looked around. Presently, the other lioness stood up and, as if summoned to do so, his lordship did likewise. They started walking very slowly, stopping every now and then, directly toward us. Chito had found a good steady rest for the Remington on a low branch. We just patiently waited, watching as they came toward us very slowly. When they got to about 80 yds. from where we crouched, I began to explain to Chito where to aim for a frontal shot.

When the leading lioness reached a point about 50 yds. from us, I was about to tell Chito to put the bullet into the lion’s mane directly below his chin. Suddenly, all three animals turned broadside to us as if they had heard something from the direction they now faced. The situation could not have been better, and Chito fired, hitting the lion fairly on the shoulder. He roared and reared forward, ran a short distance and collapsed.

One of the lionesses became very aggressive, and it looked as though I might have to shoot her, which is the last thing a professional hunter wants to do. Fortunately, she eventually slunk off after the other lioness toward a distant treeline. This was the Model 721’s first lion.

By this time, several of the leopard baits had been fed on and we decided the time had come to sit and wait at the bait from which the sign appeared most promising. A large amount of meat had been consumed from a warthog indicating either a very large leopard or more than one animal had fed.

We decided to wait in the previously constructed blind that evening and re-sighted the Model 721 to the precise distance between the bait and blind before leaving camp. The Land Rover dropped us off at the blind and we settled ourselves in as the sun began to sink toward the western horizon.

At first, it was very quiet sitting motionless in the blind until the odd spurfowl called followed by the chatter of monkeys indicating that the leopard had started to move. We tensed. He could appear anytime now, but instead a hyena came strolling warily along and stood at the base of the tree. He looked all about him to make sure the coast was clear and then started picking up bits and pieces the leopard had dropped from the kill above.

Suddenly, a very large leopard burst from the bush and there followed a brief rough and tumble between him and the hyena, both of them growling furiously. Lasting only a few seconds, the leopard sprang back into the bush as suddenly as he had emerged. The hyena shook himself, looked around and resumed his scavenging. He appeared totally unhurt and presently wandered off, passing close to our blind.

Although this was the only time I actually observed such behavior, I am sure it happens from time to time, possibly at night, as whenever I have seen a hyena approach a bait tree where a leopard has been feeding, it is always with caution, stopping and peering toward the bush frequently and never hanging about after picking up the crumbs from the leopard’s table.

Another 10 minutes passed, and I became anxious as the light was beginning to fade. Then, like a phantom, the leopard suddenly appeared in the lower fork of the tree, having approached from behind it, unseen by us. He stared straight at the blind and I whispered to Chitito, “Don’t move.” After what seemed to us a lifetime, he moved to a branch higher up and lay down on it with all four legs dangling down on either side.

The shoulder was not clear, and I asked Chitito if he felt comfortable aiming for the head-neck area. He replied that he felt totally confident so I said, “Go ahead.” Chitito fired and the leopard fell legs up from the tree. We scrambled out of the blind and when we reached the base of the tree, found a very large and beautiful male leopard in his prime stone dead. Chitito’s bullet had pierced the brain. It was a truly magnificent trophy and the Model 721’s first leopard.

We moved the safari further south to the Ugalla / Rungwa River area where luck was with us and we wound up the safari collecting kudu, sable and Lichenstein’s hartebeest. Chito could not resist the temptation to take another elephant and we tracked and killed a 65-pounder.

We had a most interesting kudu hunt. We were driving along a sandy track traversing a thick patch of miombo forest when five kudu bulls bounded across the track a couple of hundred yards ahead. Even at that distance I could tell that two or maybe three of them carried trophy heads.

I drove the hunting car to a spot under a shady tree, and as it was nearing midday had a quiet snack while waiting for the kudu to move on and settle down. I knew they would be stopping to look back from time to time and wanted to give them about an hour to settle down before we commenced tracking.

We left Chito in the car while Chitito, myself and the two trackers walked to where the bulls had crossed the track and began the very easy job of tracking in the soft sandy soil. We progressed very slowly, however, with all eyes focused ahead as we followed the spoor first through dense miombo forest then into more open scrub country where patches of long grass had escaped the raging fires of a couple of months before. Here visibility was better, and we hoped to catch a glimpse of the bulls before they realized we were following them. Surprisingly the tracks indicated the group continued moving, albeit slowly, all the time. Occasionally, scattered fresh green leaves on the ground indicated a place where the bulls had done some nibbling.

This continued for a couple of miles, and I was beginning to wonder if we would ever close with the “grey ghosts.”

We were brought to a sudden stop by a strange clacking noise emanating from behind a curtain of long grass just ahead of us. What could it be? One of the trackers indicated to me with his arms that two of the bulls were locking horns. We quickly reached the curtain of grass and crouching, carefully made our way to its far edge, and there not 60 yards away in a little clearing were the kudu with two mature bulls in the act of sparring. They would face each other then lunge forward smashing their great horns together briefly before backing off again. This was repeated every few minutes.

We crept up to a convenient tree close by, and I told Chitito to get a rest for the Model 721 and be ready to shoot. I glassed the awesome scene, noting that the two combatants carried the best heads with both sets of horns going well over 50 inches. The other three bulls were standing about watching in different directions, and although mature, they were not as good as the battlers.

“Take the one on the right when I say, ‘OK’ as his horns look more massive,” I told Chotito

When Chitito was ready and aiming I said, “OK, take him.”

At that moment the bulls were about to lock horns again, and as the shot went off their horns clashed together. The selected bull collapsed, and the other bull, assuming he had triumphed, kept up the assault on his fallen opponent. At the shot the other three bulls immediately dashed off and it was a little while before the survivor realized something was not right. Disentangling his horns he dashed off after the others. It was the culmination of a most interesting hunt

We arrived back in Nairobi with a very creditable selection of trophies all having been collected with the .30-06 Model 721 with the exception of the elephants, rhino and buffalo, which were taken with the .470s.

The Longorias were a very large family, and I conducted at least six more safaris with Chito and other members of his family and friends during the 1950s and early ‘60’s. During all those safaris, the same guns were used, which Chito had brought on the first safari, and the Model 721 was responsible for collecting most of the plains game plus a number of lions and leopards.

The Model 721 Goes to Bechuanaland

My family and I had decided for various reasons to move from Kenya to Bechuanaland, an obscure British protectorate adjoining South Africa and reputedly teeming with a wide variety of wildlife. Here, it was hoped I would be able to open up a new safari operation for Ker, Downey & Selby Safaris.

My last safari in East Africa was with Chito and a large group of friends in 1962, just prior to my departure. Chito asked that I take his rifles to Bechuanaland, as my own, for he had no intention of returning them to Mexico. He also looked forward to joining me on safari as soon as the company was established in Bechuanaland. Having guns already there would save him a lot of hassles traveling with firearms.

I established Ker, Downey & Selby Safaris in Bechuanaland in 1963 and, after extensive negotiations with the British Government and the Batawana tribe, was granted permission to operate, initially for one year. A number of my old clients were interested in something new and ready to go, so we commenced conducting safaris in April that year.

One of my earliest clients in Botswana was a man by the name of Prince Stanislaw Radziwill, a member of the Polish royalty, who was forced to flee to Britain when Hitler came along. Stas had made several safaris with me in East Africa and was anxious for the new experience. He was an ideal client, easygoing, humorous, and a good sportsman who loved his champagne.

We started hunting with Stash using the Model 721, and had collected a few animals when, on the evening of the third day, we came upon a herd a sable. The bull had a fantastic head, and I had never seen another sable that even came close to that size. His horns reached well over his back and he was jet black. The herd seemed skittish, and when we tried to stalk within range, they just took off into the dense mopane forest. It was late, the light was bad and we never came up on them again that day.

Stash was so eager to get that sable that he very seriously suggested we forget everything else and concentrate on that one bull, even if it took the entire safari. We concentrated on finding that bull for a day or two and came upon the herd twice more, but on each occasion, the bull was not with them. We searched the entire area around the herd in case he was merely lying down and taking a rest from the herd, but found nothing!

Then, on the fifth morning, we spotted the herd again and there he was. The herd was resting not far from the Khwai River, which was completely dry at that time. The herd appeared to be unaware of our presence so we took our rifles and slid down into the Khwai’s fairly deep dry watercourse and crept along it until I figured we were more or less opposite where we had seen the herd. I eased up the bank very carefully and there they were about a 100 yds. distance, with the bull even closer. I motioned Stash up to me and we crept on hands and knees the short distance to a tree from which Stash could get a good rest. We eased up behind the tree with all the animals still seemingly unaware of our presence, and Stash got ready to shoot.

The bull was no more that 75 yards away, but angling slightly away from us. Stash began to aim, and I was anticipating the shot when he raised his face from the stock of the rifle and whispered to me, “He is standing at the wrong angle.” I whispered back, “Just hit him a little back from the shoulder the bullet will range forward into the chest” As I spoke with Stash looking back at me, the shot went off and so did the bull along with the entire herd. Stash began to curse himself in English and, I presume, Polish, too. I thought he was going to cry.

“Come on, Stash. Let’s get back to the car and try to locate the herd.” I said.

We soon found the herd again, crossing a flood plain, but the bull was not with them. As this bull had so often been absent from the herd, I thought he might have left them again, so we went back to where Stash had fired the shot with the intention of trying to track him, which was no easy task in scrub mopane bush.

We found where he had been standing when the shot went off and began to track. We had gone about a 100 yds. perhaps a bit further in the scrub mopane, when suddenly we came upon the bull, laying stone dead. The bullet had entered exactly where it should have, had Stash been aiming through the scope. What a fluke!

To this day, I consider it one of the most inexplicable incidents I have ever experienced in all my years of hunting. I was not looking at the animal when the shot went off. I was looking at Stash. Otherwise, I would probably have noticed something to make me think he had been hit. The sable was a grand animal, in his prime, pitch black body contrasting with white belly, rump and facial markings. The horns measured just a fraction less than 50 inches. After this incredible experience, we resumed our normal hunting, and Stash collected the rest of the animals he was after in the Okavango and Kalahari areas.

In 1965, I was on safari with a client who had been with me the previous year and, as my son, Mark, was on holiday from school, the client very kindly invited him to join the safari for a while. I realized that during the time Mark would be with us, he would have his eleventh birthday. I suggested to my client that if it was agreeable with him, it might be an idea to allow Mark to shoot a buffalo on his birthday. Mark handled a rifle well and had already shot several animals with the Model 721. There were no restrictions on age or calibers in those far-off days, and I had some 220-grain solids in my ammo box for the .30-06.

The client thought it a splendid idea and, as buffalo were plentiful, we would not have to go to great lengths to find a nice bull.

Mark joined the safari and, on the morning of his birthday, we all wished him a “Happy Birthday,” and then set off hunting. At about eleven o’clock, we came upon a herd of buffalo resting in the verges of a small plain with some animals drinking at a small waterhole in the center of it.

Until then, we had mentioned nothing to Mark about the possibility of him shooting a buffalo. The client now said to Mark, “Wouldn’t you like to shoot one of those buffalo?”

“Oh yes, but I don’t have a license,” Mark replied.

“You can have one of mine,” the client offered.

“Thank you very much,” Mark said, beaming all over.

We loaded the Model 721 with the 220-grain solids, then Mark, accompanied by me with my .416 Rigby, and a tracker set off to stalk the herd. It was fairly easy to get within a 100 yds. of the nearest animals, which were either cows or immature, but from there it meant a hands-and-knees stalk. We had spotted a nice old bull off to one side and decided to try for him. We eventually reached a small anthill about 50 yards from the bull, and I helped Mark get the Model 721 settled and steady on the anthill, and explained just where to aim. Mark fired and the buffalo lunged forward, and ran off with a broken shoulder. He joined up with the rest of the herd, which, by then, were milling about on the plain.

Through the binoculars, I noticed the old bull stagger and finally collapse. On examination, we found that Mark’s bullet had hit him squarely on the shoulder, smashing the shoulder bone, and penetrating the vitals. Mark was as pleased as any young boy could be after having been given something beyond his wildest imagination and his smile in the picture shows it. This was the Model 721’s first buffalo.

Several safaris with the Longoria family and their Texan friends followed and the Model 721 and the shotguns saw constant use on these and other safaris over the years.

When Ker, Downey & Selby Safaris embarked upon building a tourist lodge, I employed quite a large number of workmen for the job. The Government generously agreed to grant permission for a “pot license,” allowing a limited number of animals, even including buffalo, to be taken monthly in order to feed the workforce. The Model 721 was the rifle used to do this job.

In Africa, there is an insect, which will build a nest of green leaves and mud in any small orifice it can find—a rifle barrel is an ideal place. Too late, we discovered this had happened to the Model 721 during a period when not in use and, upon inspection, it was found that about a two-inch section of rifling was completely eroded, which totally destroyed the rifle’s superb accuracy.

What a sad end this appeared to be for a great old veteran of the African safari, and I determined that this would not happen. A friend kindly brought a premium-grade Douglas barrel from the United States for me, which was fitted to the Model 721 by an excellent gunsmith friend of mine in South Africa. The Model 721 took to the field again with a new lease of life … its first trophy a superb sable.

It is impossible to ascertain now the number of significant trophies this very standard rifle has accounted for, but it would be a proud accomplishment for any rifle carrying the name of any of the top English gunmakers or, indeed, a very expensive custom piece from one of the well-known American custom rifle builders.